Parallel channels – Interview with Dániel Cseh and Attila Pálfalusi

We spoke to the two media artist about mechanical facts and human errors in connection with their most recent exhibition. Their media art explores understanding and self-reflection, as well as subjects such as fake news, hacking and humanism. Dániel describes his latest works Ideometry and VCCTV (Very Closed-Circuit Television), and Attila his installation The Critique of Pure Reason. With both of them being teachers at the MOME Media Design department, their teaching experiences in addition to their creative work were obvious subjects for discussion. At the exhibition, behind the security devices covering every space, you can eventually find yourself with a hand in the chamber pot – an idiom used to suggest coming in for a rude awakening.

Attila Pálfalus and Dániel Cseh

I came here labouring under the assumption I was going to see an epistemological exhibition – in other words, an exhibition about the possibilities and issues of understanding.

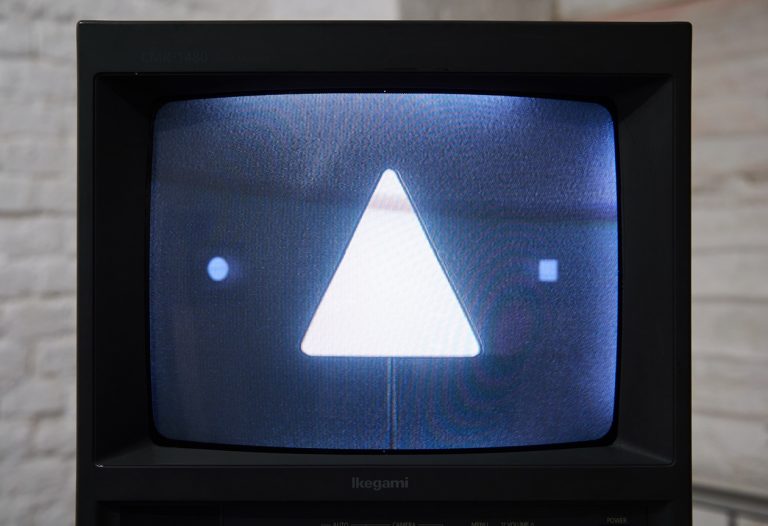

Attila Pálfalusi: I think it is a good interpretation – we might as well describe it as epistemological. In the first room for example, what you see is an ‘argument’ between three TV sets about what they see, without being able to come to an agreement. It is a clash of image against image, despite our tendency to regard television, along with camera, as a potential means of understanding. And yet, these sets are unable to agree with each other – though according to the ‘two heads are better than one’ principle, this shouldn’t be the case.

Dániel Cseh: On top of that, though reality is I captured with the help of devices that lend credibility (security cameras), there is no common denominator. There are only some fractions of a second when the shape on the screens takes a turn and there is opportunity for at least a partial agreement. Most of the time, they are looking at the same thing but see something different. Interpretations inevitably lead to conflict.

In this age of information chaos and fake news, it is difficult to view your works in a context other than post-truth. To what extent are you directly preoccupied with this post-fact world? Was it the related public discourse that gave you the push to create the installations of the exhibition?

Attila Pálfalusi: As far as I’m concerned, I wouldn’t call it a push, though I find the unintended allusions entertaining.

Dániel Cseh: Subconsciously, you can perceive its effect, but post-truths were not the starting point for me, either. It is undoubtedly a related issue. As a result of post-truths, you can argue until you are blue in the face without reaching any conclusion.

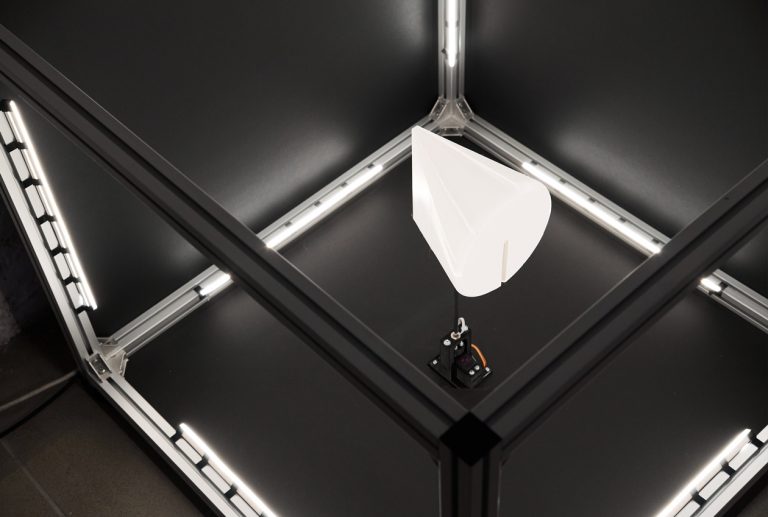

Dániel Cseh: Ideometria (2022)

Looking at these old screens, I’m intrigued by how you take a seemingly outdated technology to raise questions about depicting reality.

Dániel Cseh: True, but importantly, these are security devices. If, with some exaggeration, you regard optical images as authentic depiction of reality, the same is doubly true for security cameras and screens. We tend to give credibility to information because they are produced by the devices, without actually reviewing their content, and we can just as easily choose to question anything when it’s more convenient, knowing that the technical requirements are also given for that – see deepfake for instance.

It is precisely these devices you take apart or open up in the second section of the exhibition.

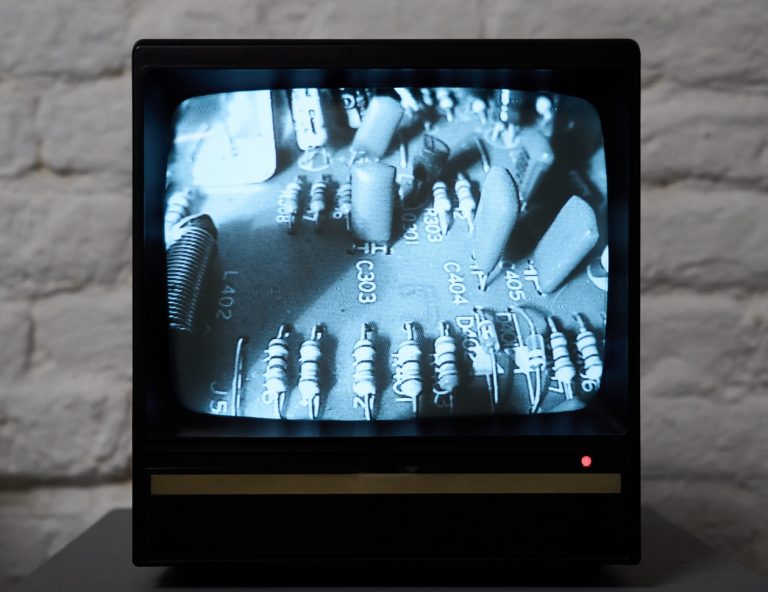

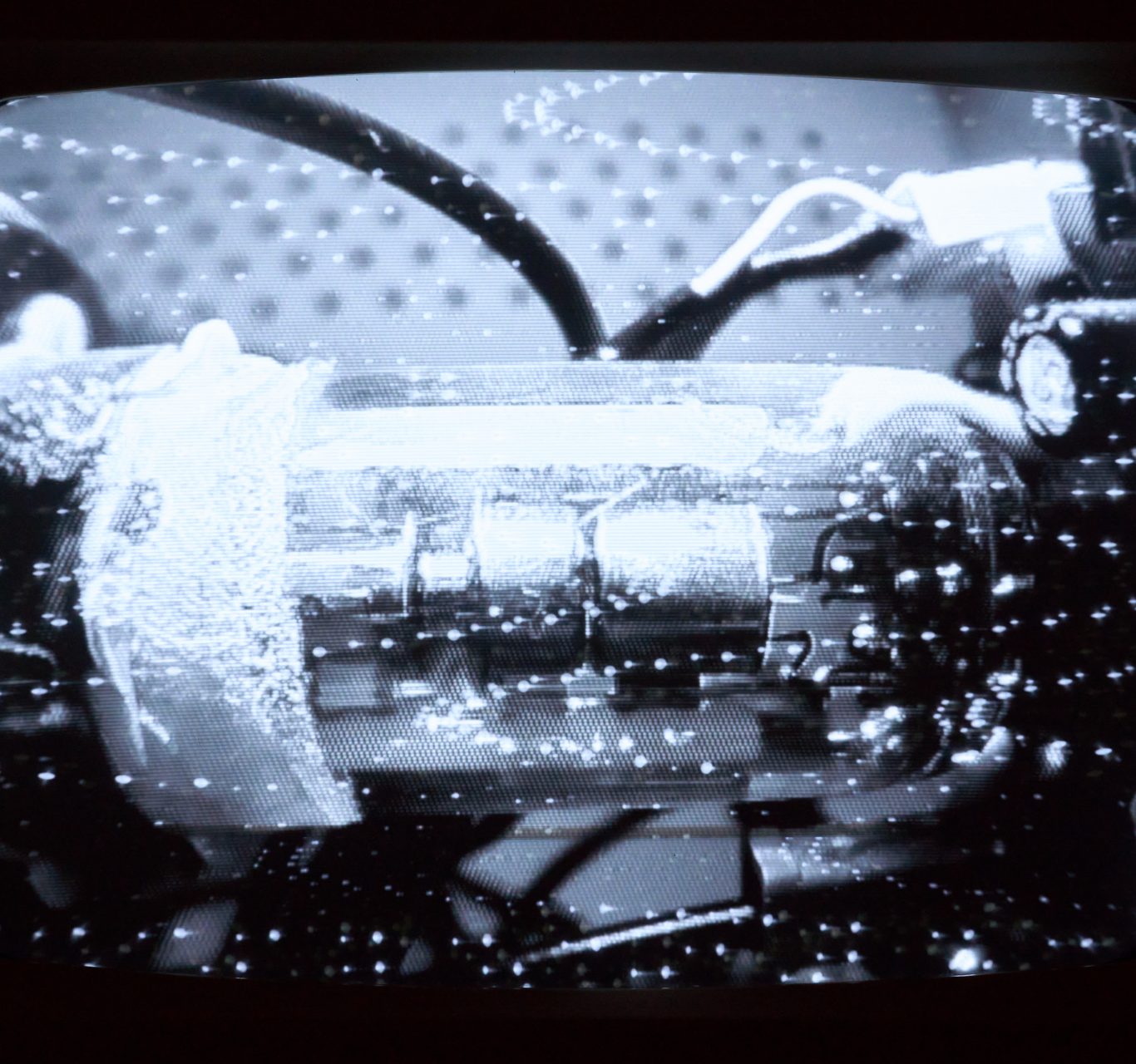

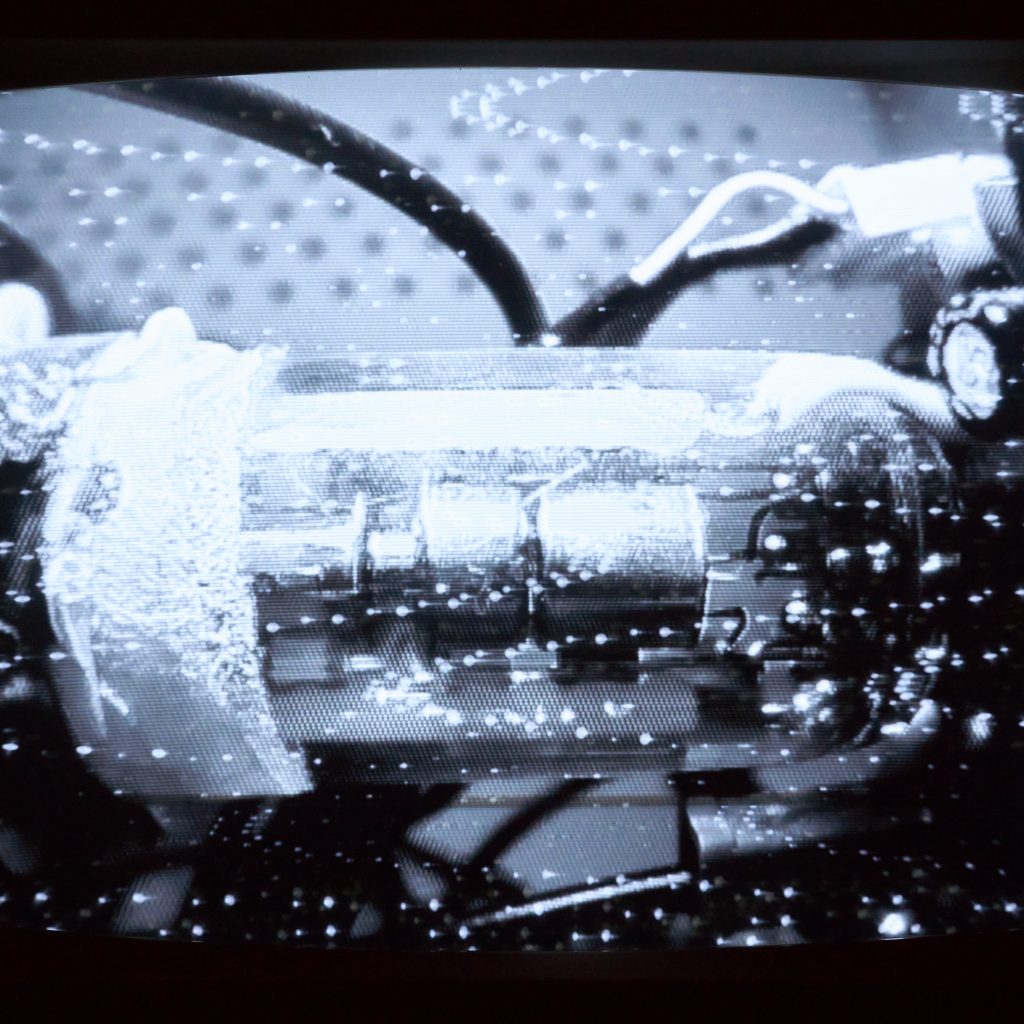

Dániel Cseh: The installation VCCTV (Very Closed-Circuit Television) features security screens that were rendered ‘harmless’ – in a way, they are being punished. They no longer watch the outside world, but rather are forced to look inwards, frozen in eternal introspection. Their self-containment is so complete that the image is actually created inside the device using an inserted camera, showing a portion of the screen’s own components.

It is a sort of mechanical striptease…

Dániel Cseh: This has a magnificent byproduct, since constantly exposing the phosphor layer in an CRT screen to the same image will result in the burning in of an inverted version of the same image. So just like with photography, there is a fixed image, only in this case it originates in the inside of the machine.

Dániel Cseh: VCCTV (Very Closed-Circuit Television) (2022)

You turn a technological device that works essentially like a black box inside out, used by some on a daily basis without understanding how it works. Doing the same with devices today, such as a smartphone would be way more difficult.

Dániel Cseh: The decision to go back to a previous technology in a sort of media archaeological gesture is no coincidence. These devices can be disassembled in a meaningful way to analyse them, gaining a better understanding of what is happening and why. Due to their structure, they have a dimension that could be interpreted as an internal space, monitored by the inserted cameras.

Attila Pálfalusi: These were more ‘generous’ technologies…

Dániel Cseh: I would have a hard time taking the same attitude to an LCD screen or a smartphone. Though I might understand how some of their parts work, I would still be unable to find a hold on them. The screens here have retained something from the time they were in use, such as a layer of nicotine that coats the surface. If you draw your finger across it, in your mind’s eye you can practically see the chain smoking security guard watching the screen with bleary eyes for decades.

The contemporary means of surveillance capitalism are indeed more elusive, and do not enable the type of identification and turning of inside out that VCCTV apparently does. Do you still find disassembling and hacking-like diversion in these circumstances? In your experience, how does the latest generation feel about this?

Dániel Cseh: For us, this is an essential ambition. Not just in terms of the exhibited artworks, but also when it comes to teaching at the Media Design department. I normally draw inspiration from the technology itself, and it sometimes involves going to the annual cleanout, loading whatever I took a fancy to into my car, then taking it apart and seeing what I can make out of it. I also follow Hackaday’s page featuring some of the maker and DIY culture’s opinions most critical of the establishment. In Nam June Paik’s words, we create anti-technology at the service of technology. I am certain that this also influences the way I think, and when I take something apart, I use the same approach to it.

Attila Pálfalusi: I, too, think it is a vital part of the training and the students’ approach. Whether there is a broader receptiveness to it is a different matter – disassembling and reassembling something is a lot of effort and dirty work. Let’s just say it is very far from the sterile and idealistic image that most people have of designers. And yet we see that our students can relate to this modus operandi with a sort of repair shop feel to it, and also to what we want to stand for in media art.

Was it your shared teaching background that made you want to create a joint exhibition?

Attila Pálfalusi: This was a natural connection that we had. We are colleagues as well as friends, and we discuss each other’s works. As they started to take shape, we saw that they had a lot in common. They might be dissimilar in form, but similar in content. They all shared motifs of understanding and self-reflection.

Attila Pálfalusi: The Critique of Pure Reason (2022) / Dániel Cseh: Ideometria (2022)

There are also overlaps in terms of kinetic components – both “Ideometry” and “The Critique of Pure Reason” use mechanical motion.

Attila Pálfalusi: They do. In my case, engines are used to help the suspended hands rise towards epiphany, only to come to a sudden halt at the critical moment. The few grams difference in the weight of the bound pairs of moulded hands is added up over the long term and will shift the system towards one or the other. Essentially, we are all bound together, and it’s up to us…

…to what extent we let our hands end up in the chamber pot?

Attila Pálfalusi: That’s right. And the more time we spend together, the more someone will end up like that. At least that’s what the technical interpretation of the installation tells us.

But that also means one of us will be able to escape the threat of the chamber pot altogether.

Attila Pálfalusi: True, but we don’t know what’s better – to end up with your hand in the chamber pot or not. For that matter, it depends on what’s inside the chamber pot… Do you prefer floating around and not getting the proof required to confirm a suspicion to getting proof even if it means a rude awakening? This awakening might not be at all pleasant, since you end up with a hand in the outcome of your illusions that is undoubtedly yours. The way I put it is that this installation is about the aesthetics of errors, and will serve as inspiration for several works of art in the future.

Attila Pálfalusi: The Critique of Pure Reason (2022)

Can you see a cycle taking shape?

Attila Pálfalusi: Yes, you could say that this installation is the first instalment in a philosophically linked series or a cycle, so to speak.

I am more inclined to suspect a personal story or autobiographical inspiration behind your work than Dániel’s two installations.

Attila Pálfalusi: That might be the impression you get, but I, too, am mostly interested in patterns. How do we deceive each other and ourselves? We use whatever little information we have to extrapolate, foresee possible scenarios and speculate about the future. The chamber pot, however, is there, and ending up with your hand in it means things are sure to take a different turn because you wake up.

It is still a more personal work than the other two because it has man as an individual in its focus, afloat among various facts and certainties. The security screens, on the other hand, are about the illusion created by systems posing as custodians of objectivity. With “The Critique of Pure Reason”, I’m not even sure whether man is capable of understanding or wants to learn the truth at all that is generated by our technical networks on a systemic level.

Dániel Cseh: I think that is at the root of all three installations, only in my case the technical metaphor I use is clearer and more direct.

Attila Pálfalusi: Yes, even though Dániel’s work appears to be very mechanical in form, it contains some very human motifs. I use softer forms, both the hands and the chamber pots are infinitely human, but they are operated by a machine, which means there is something mechanic about its systemic operation. In this sense, there might be a twist to these works: what one appears to have on the outside the other seems to have inside, and vice versa.

Attila Pálfalusi: The Critique of Pure Reason (2022)

The key is human in the machine and machine in the human?

Attila Pálfalusi: Studying the relationship of man and machine dates back a long time in media design, and strangely enough, machines are generally used to represent man. You could say both are better at describing each other than itself and the opposite is also true. Once you take man out of a technical system, it automatically becomes all about man. A system with a lot people might, after a while, start telling you something about the machine. In this respect, it has not only post-human but I believe also ‘pre-human’ implications.

Dániel Cseh: Starting from the 60s, robotic art ceased to be about machines. With nearly each work of art, you can identify the human quality underlying a metaphor without the actual presence of man to interfere with the interpretation. Even though I’m looking at or listening to something that is not about man, it is clearly about a machine-made reading of man. You can trace this concept farther back in time – man was first described as a machine centuries ago. This metaphorical language is also typical of me to some extent, but at the same time I try maintain a colder and more distant approach in terms of form.

Attila Pálfalusi: As you probably figured out by now, we are in fact deeply humanistic. We are mostly interested in man, only we are trying to hide it.

// /

The exhibition was on display at MaMü Gallery between 24 June and 8 July 2022.

Author: Ákos Schneider