Delving into Hungarian New Age Communities

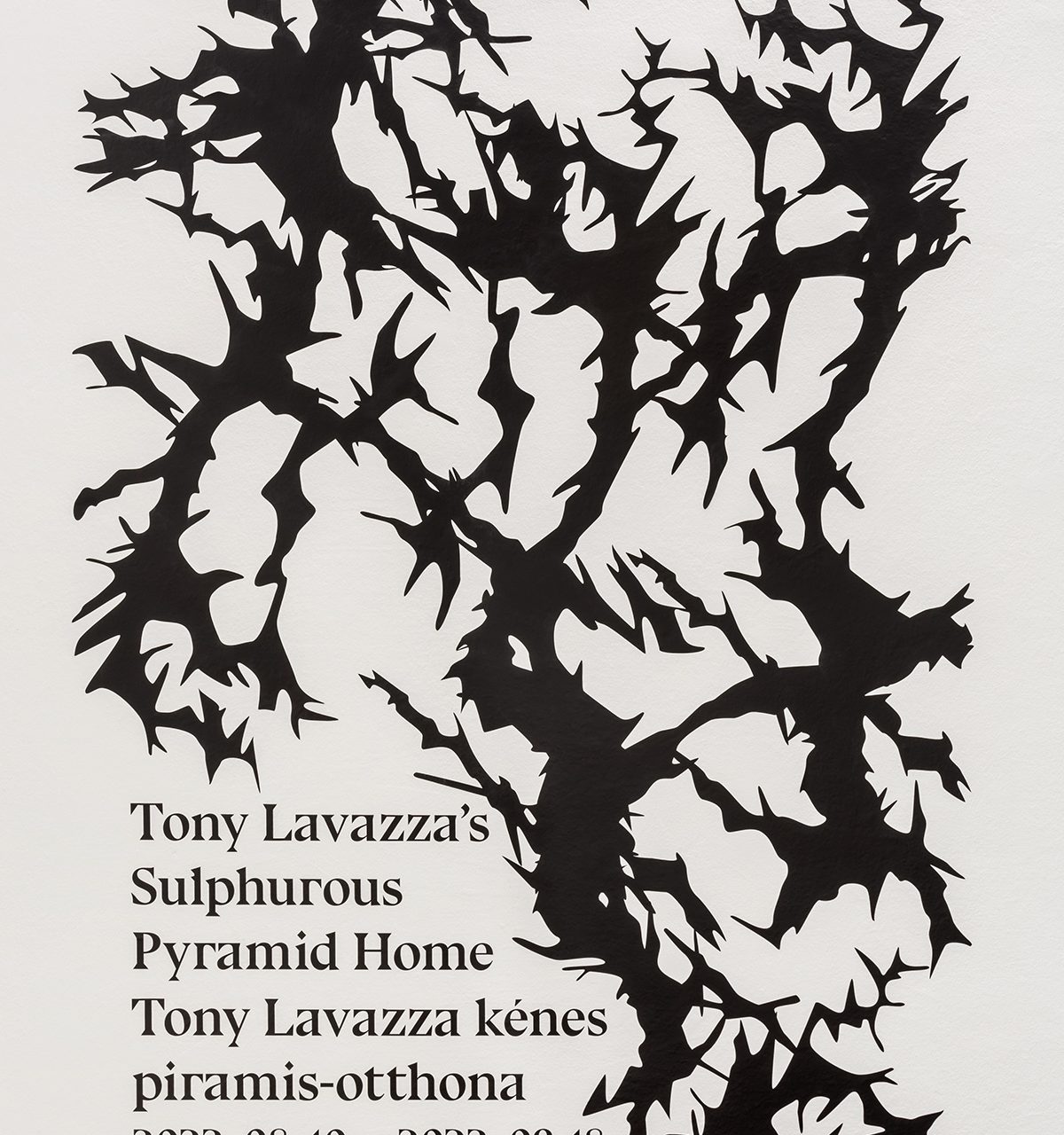

Interview with Chloé Macary-Carney on the occasion of her exhibition Tony Lavazza’s Sulphurous Pyramid Home. The exhibition was based on the artist’s research into the ritual sites and practices of New Age communities, more precisely the geographical and historical dimensions of Hungarian New Age communities and witchcraft, their political links and the myths surrounding them. Chloé Macary-Carney was a member of the Budapest Gallery artist residency program in 2021. Interview by Anna Keszeg.

What does New Age mean to you?

“New Age” is this idea of an ideal new phase in human history where civilizations from around the world will have found a state of peace, of justice and symbiosis with nature and between civilizations, a sort of utopia that new age communities try to reach or create through the spaces, practices, and moments that they create together. Paul Heelas describes this well in his publication “The New Age Movement” and what I find interesting in these New Age communities, is how they are founded on the paradox of our post-modern society: they are truly a product of the modern era and of a globalized vision of productivity and efficiency. There’s this idea in the New Age movement that by practicing the rituals, purchasing the objects of this culture, one can become a more peaceful person, it’s the same idea of the self-made man, this idea of a meritocracy that is very perverse because it also means that we are never good enough as we are and that we must constantly prove ourselves to find a place in this economy which is ever more competitive with the free market. This way of thinking is obviously in the interest of companies and Heelas explains the intertwinement of globalization and the growth of this movement well when he connects the birth of new tech companies in California to the birth of this movement. Another paradox is how these communities prone a sort of localism, and anchorage in “ancestral traditions”, when in fact they are made possible with internet and this direct access that people have suddenly to cultures from other parts of the world. There is this cultural appropriation in the practices of these communities that is made possible and accelerated with this new globalized culture. Finally, what is also interesting is that these communities sort of position themselves in opposition to the work culture and the consumerist economy and culture that we live in today, all the while being totally a product of that economy and creating a market of “wellness” on their own as well. I could go on and on about this…

What were your expectations before Budapest?

Before coming to Budapest, I had planned my whole project around a specific group Magyar Boszorkányszövetség that was founded by a man named Cézár Abafi. This was really the group that interested me most and I hoped to meet with the practitioners, but upon my arrival, I discovered that Cézár, the leader, was dead and since then, the group had stopped their activities (in 2011). I had to dig through random articles and Facebook posts to finally stumble upon one of the members of the group, Vilmos Binger who I was thankfully able to meet and exchange with. It was hard to get information from him though because it turns out he wants to make a museum about the history of that group, and for many other reasons too, anyway, from that point though, I just started reaching out to other people who were a part of different new spirituality groups and the project ended up growing allot more into a search that led me to places outside of Budapest, like Kiskunfélegyháza, Tokod, Szeged to find these groups.

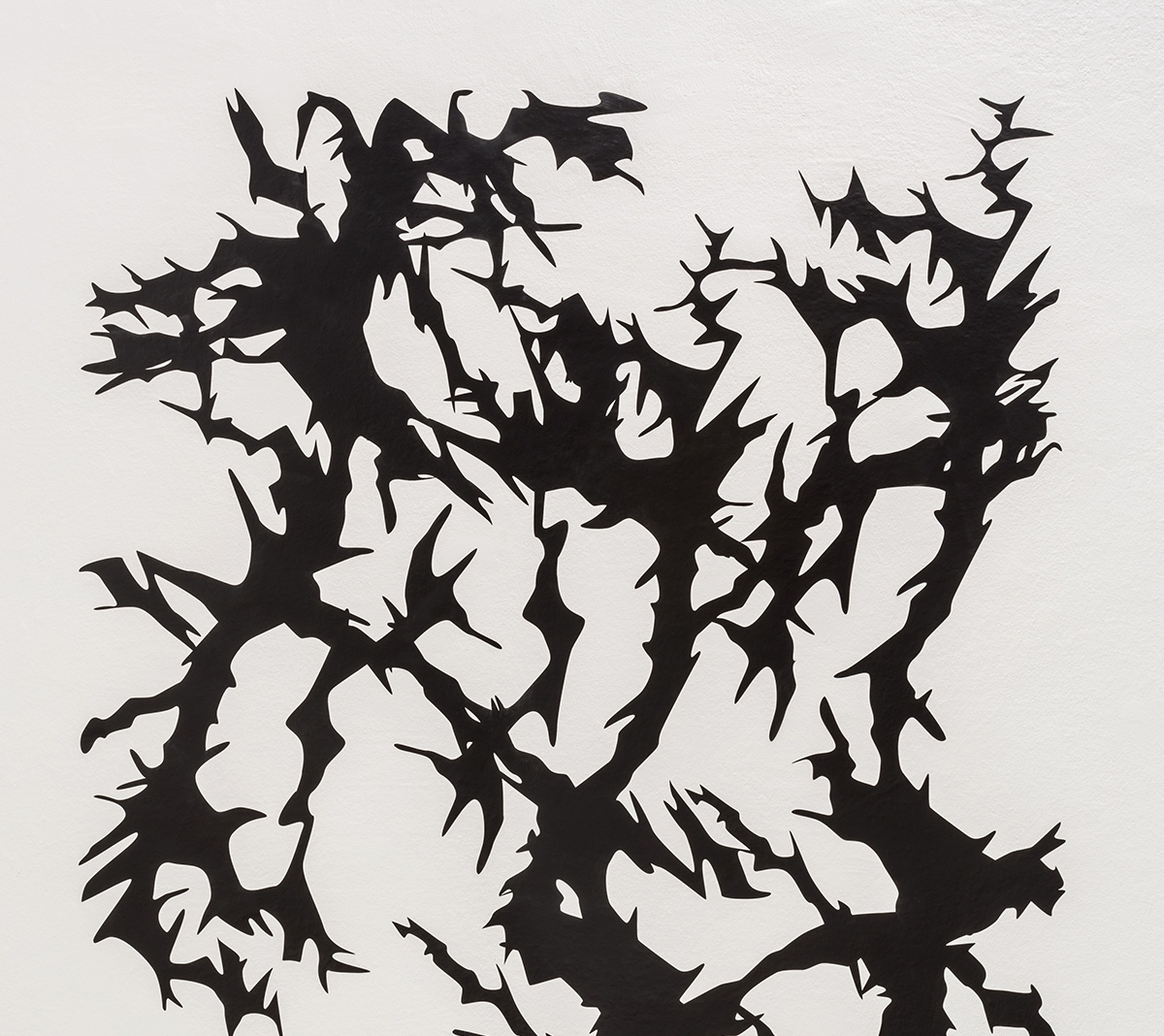

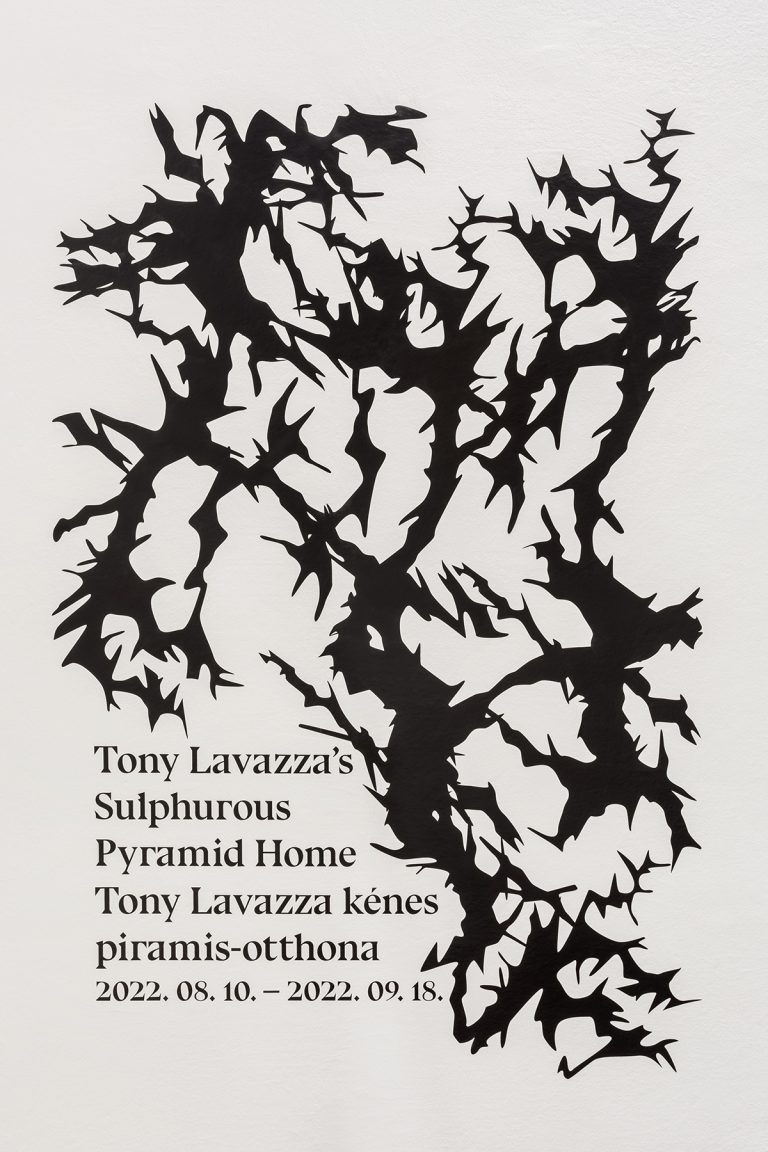

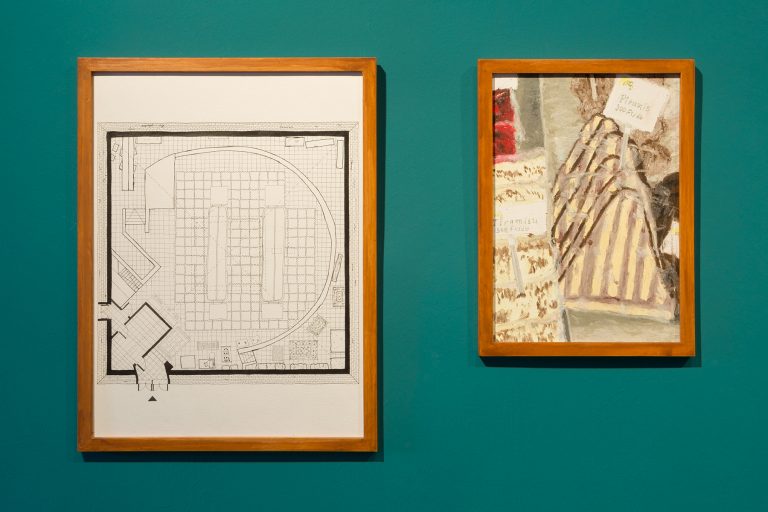

Interior of the exhibition “Tony Lavazza’s Sulphurous Pyramid Home” (2022)

What other geographical impressions did you have on New Age rituals and religions?

These practices are a global phenomenon, which also interests me a lot because it then makes you look at what global dynamics and transformations created this world-wide culture, it is not just a thing you find in a few regions. Despite this though, I discovered that there is also a set of historical events and political contexts that shaped the different new spirituality groups you can find in different regions. In the case of Hungary, during my interviews with people on site, they mentioned the soviet presence as stifling their freedom of expression, of creativity and religion, which therefore pushed some to create their own religion under the radar. It was surprising for me to hear many spiritual practitioners mention the importance of indigenous American’s traditions as being an inspiration for their practices. There seems to be a parallel that people make in these post-soviet countries, between their experience of being crushed by an imperialist nation, in the same way the native American people were erased by the Europeans who founded the United States of America. So, there is a global movement of these New Spiritualities which have popped up around the world, sometimes in search for the “true”, “ancient” or “traditional” spirituality that existed in their region, sometimes just inspired by the practices they find online or via these communities who take from here or there.

Who is Tony Lavazza? What’s in the name? Is it important for you to draw a profile of him?

Tony Lavazza is an amalgam of ideas that I wanted to synthesize in this name. When I went to Kiskunfélegyháza to document the pyramid that Vilmos Binger’s witch group borrowed for some rituals in the 90s, I stayed in this hotel that I had reserved online not far. When I got there, I found out it was actually on a farm, a few bedrooms installed above the horse’s stables. That farm belonged to a man named Tony Lovarda, or something like that. I liked the idea of a very masculine name like Tony, and mixing it with a more eccentric Lavazza to balance that more masculine name and just sort of building a character out of the experiences, the people I met during my time in Hungary, that would be me perhaps, but at the same time perhaps an alter-ego from another time who had a passion for these groups and who was also a bit dubious of their magical-spiritual capabilities. The water in that farm-hotel smell so strongly of sulfur that it felt pointless to even take a shower there and the whole place smelled of that sulphureous water. I asked Tony’s wife, Betty, about the water, and she really enthusiastically boasted about the health benefits of the water that came from a natural source on the farm. I found that to be such a funky atmosphere, that was also a bit mysterious and references as well the hot bath culture in Hungary, so I also wanted to add that into the title of the exhibition. What was important for me was to have fun really because the whole experience was an adventure of sorts and it’s important, I think to not take yourself too seriously, especially when making a solo show, there’s so much pressure on trying to do something nice and that makes sense, I don’t know. What I really wanted to do was create a feeling of being in this researcher’s home with remnants from these strange occurrences and discoveries which are a bit absurd or nonsensical, but which are also true for many people. In the end I didn’t uncover some secret or huge magical truth, but I did meet these people who really kindly welcomed me into their world and their communities, the idea isn’t to make fun of these practices or these people either and it felt like the best way to describe these adventures then was to create an alter-ego that is confusingly also myself all the while being a cooler, more fun and more sarcastic me. Alter egos are practical in that sense, and just more fun because there is that mystery where you don’t know what is real from not real and what is serious or not, in the end it is all a mix.

What was the inception of this artistic research? How did you proceed in building the map of Hungarian New Age communities?

This research originally stems from my explorations into the “red tents” in Paris, which are sacred feminine circles of discussion. They have become a kind of world movement, you can find them anywhere in the world, and they are a new age space that employs the tools, the aesthetic and verbal language of those communities. That space of the red tent really inspired me because women leave it feeling connected to their purpose in life, to a community of women they don’t know (it’s usually total strangers who find themselves in these discussions), but that they feel supported by in a larger sense. I came to Budapest with the idea of exploring how these new spirituality groups may have created safe spaces for people who felt cast out of society, and initially I wanted to invent a new space or new rituals, inspired by the observations in Hungary, eventually integrating into furniture these rituals. Once I started the research on site in Budapest though, I really had to dig for information, meet with people in random villages or shops and I ended up meeting people who had unique characters, I ended up just following that adventure, I guess. It was super hard to get into these communities too, their rituals or ceremonies are quite guarded because it doesn’t take much for one person to ruin the ritual, any stranger in a group can also ruin the other member’s feeling of safety and security in their ceremonies. I started to realize that I was way too attached to the goal of uncovering some mystery or some secret sacred space in Hungary, I got really hung up on finding signs and documenting “authentic” ancient objects or traces. Júlia Hermann from Budapest Galéria, who organizes the residency I did here, and curated my exhibition, presented me to a witch specialist, and she knew so much, she has been studying these groups for years, and many other professors at MOME or other universities in Hungary have dedicated allot of their work to understanding these groups. Considering the time that I had on site, I tossed aside the idea of mapping out all these groups and practices and instead just wanted to tell the story of this researcher’s adventure which is not as precise or scientific nor is it very in depth, but I do think that experiences and stories can tell allot in other ways that scientific articles and thesis cannot. Also, everyone loves a good story.

You use a lot of different sources in the exhibition (objects, the Luca-chair, visual documents of witch trials, oral interviews, etc.). What does it mean for you to work with such different materials? Is it intermediality, intermodality? Is it a way to connect with the complexity of the issue?

I am a licensed architect so that influences my work. I like archival documents and tracing things with different sources. It’s still a challenge for me to totally connect the different elements, but in general I have a hard time sticking to just one thing, or just one medium. I like making furniture, I like drawing, I like writing and I like talking with people, so I did those things while I was here. For this exhibition more specifically, I wanted to play with the codes of the detective who looks for traces and documents anything they can find whether that be a brochure picked up on the street, or some found object. There are allot of things that I didn’t put in the exhibition but that I did collect. I took allot of really, really bad black and white photos on the go, with a little old 35mm film camera. I also talked with some people that I didn’t mention in the book after all just because their story line was still open ended (I got covid at the end of my residency which abruptly put a stop to some parts of my research). I’ve never thought about this multi-medium format of my work as a way to connect with the complexity of an issue at hand, I think it really stems from my practice as an architect, being interested in drawing out floorplans, and conducting almost anthropological work with interviews and historical research. It’s true that I am a bit attracted to the idea of the detective’s case file with many different objects and elements in it, I suppose I like the format of the “clue” which leaves allot of room for interpretation and opens the door to play, to subjectivity and interaction with the subject at hand. But as you can see from the exhibition, I wasn’t totally a perfectionist in my method because I was also in a country where I had no understanding of the language nor a sturdy comprehension of the history and politics there, so perhaps this detective game was also the best way to try to interpret the random bits and pieces of information I could discern and pick up here or there. After all, maybe your right and it is a way to connect with the complexity of the research, I never formalized it that way though.

How do you link history to contemporary social issues? What dimension can give such a historical, anthropological investigation to contemporary forms of activism? As you are a founder of the Woman Cave Collective, this activist dimension is an important feature of your work.

I am always making mistakes on historical dates and periods, it’s quite embarrassing but I am really interested in it, and I am also still confused about it. Growing up in America, I feel like we were told allot of things about our past that were totally not true, and then we were told some things that were true, and you always wonder what parts of history still hold true today. It’s interesting to see how history is retold and rediscovered through the militant movements of today, like for example, I’ve been interested lately in the Middle Ages, as a lot of artists have these past few years honestly, and I’ve been reading about how women in fact had a superior place in society than later on as for example in the 17th century. We tend to think that history is linear, especially regarding women’s issues there’s this idea that little by little women have been gaining more rights, when, that isn’t so. I don’t connect with the term “activist”, maybe Léticia Chanliau, with whom we founded the collective would say otherwise, I can’t speak for the both of us, but I feel quite bothered by that term which is seen as a sort of medal in our society for those whose job would be to defend the rights of everyone, and then it totally ignores and erases the work of people who do good things in different ways daily… With our collective, we create spaces (whether they be printed or physical) that allow for discussing storylines that were erased from history, disregarded by those who guard the keys to knowledge and academia, and we hope to make space for people today to express themselves. We want to make visible the work of people that too often there is a tendency to forget because they have been erased from institutions, from school programs and culture. We are really interested in craft practices that were disregarded by the art world and erased from the pages of history books just because they were considered “Feminine practices”. Those practices also forged community and that is powerful. Last year we worked allot around the practice of patchwork for example, which is cool because it’s about reusing old bits of fabric to give them a new use, and it’s also about community because women would meet up at “quilting bees”: they would go over to someone’s house and together work on one quilt at the same time, bringing over pieces of fabric they had. It was a time for these women to chat, to share their know-how all the while working on a common piece, that is super cool to me, and it’s not often that we highlight collective works that people make in such a disinterested way. This patchwork craft is so meticulous too, I could go on and on… all this to say though that.

The exhibition works with a strong sense of spatiality. We are in the private space of Tony Lavazza, an intimate yet public space. Because it is exposed. Why did this hybrid display matter to you? As someone interested in the relationship between gender and space, how can the working space of a researcher interfere with the nature of the sources? How does this private space and the produced book articulate different material logics?

Yes, I am an architect on top of my more recent work in art, and I like making furniture and making things with my hands. This research into these new age communities originally stems from my interest in the spaces that these communities create for themselves, and the esthetic language they employ to create a feeling of security and protection, healing. While in Hungary, I was really interested in the history of Hungarian furniture, the meanings behind these elements of the home, like for example the wooden chest that a young married couple is given after their wedding, or for example the way the dining rooms were set up in rural homes. I read some books on Hungarian traditions of this sort and visited some ethnographic museums which present these pieces, and it really inspired me to play around with these new forms, with also the painted motifs on these objects, that I found cool. Some cool angle chairs in the art nouveau villa in Budapest inspired me too, some chairs in the changing rooms of the hot baths in Buda, just a few things like that caught my eye. I like making furniture, and originally, I had this idea that at the end of my residency I would make furniture that integrate the rituals I had studied into their form. I didn’t end up really having time, space, and a budget for that, I guess. It’s still a project I would like to develop if I have the chance. So, this hybrid display mattered to me because I wanted to create a space that people who come could activate and play with. The idea was that visitors could add into that story, and participate, or personalize the space by moving the furniture around, using it during meals, workshops or any sort of event that would activate this space.

What is the global geopolitical importance of Hungarian New Age communities in your artistic practice? As someone who grew up in-between two cultures, worked on issues of K-pop and has a strong Japanese experience, what do you think about the cultural resources of those local communities highlighting global processes of community building?

Yeah, I grew up in Los Angeles which is a horrible city to live in but also a cool place because there are so many different cultures in one vast city. To add another layer onto that, my mom is French, and my dad is Irish American, so I was eligible for a grant from the French government to go to this private French-speaking international school. It was a very privileged niche of a community made up of kids from around the world. I don’t know how to really describe it, just I feel like I am more a child of globalization than a child of Los Angeles or American culture because most of my family and friends are totally disconnected from their origin land or whatever traditions they could have had. I grew up in America at a time when kids started having their own cellphones and internet was becoming more and more accessible, so we were growing up in this hyperconnected world culture that we didn’t realize not everyone necessarily have access to either. It’s a weird feeling to be able to go anywhere in the world and have cultural references in common with almost anyone just because American culture kind of dominated the world for a while. Tons of people grow up far from their family and live in countries that are not “their own” but actually are because that is just where they live in fact. Anyways, when I was exploring Kpop culture, I got really interested in this idea that you can be more indigenous to this very globalized culture that is a product of a neoliberal market, you can be more a child of that world culture than your “roots” or the “traditions” of your ancestors, even if this culture is one that you fight against, it is somehow also just a part of you. In that globalized context though, there are communities that form, there are safe spaces that people create and maybe that is kind of where my research into Kpop and my research into new age communities meet one another. These contexts are interesting to me because of the paradox that in these very globalized cultures that are created from not cool economic situations and a whole context that these individuals don’t truly have control over, somehow, some people build earnest spaces for friendship, kinship, and shared interests. More specifically, these spaces are welcoming to people who are queer, as in people who differ in some way from what is usual or the norm. That’s really cool to me, that is what I find neat about these niches, I don’t know if that answers your question.

I never tried to situate this project particularly in regards to my artistic practice as some sort of linear trace that is predefined and organized. I had this crazy rare and lucky chance to do a residency in Hungary, selected on the premise that I would research a specific witch group who turned out to be inactive after all, and it was a really cool way to explore these ideas and discover the new age communities in Hungary, I guess that’s how I can contextualize that project in terms of my practice? Someone gave me a chance. Unfortunately, it’s hard to have agency over your artistic practice and say I did this or that because it fits this way into my practice, and that’s because for most artists, you don’t make money off your work, and you do need money to pay rent and eat at the end of the day.

In one of your art-profiles I’ve seen that you defined the tool of storytelling very important for your artistic practice. Why are stories important to you? In what way can stories help the restructuring of this artistic research material? Is the story of Tony Lavazza a linear or a non-linear one?

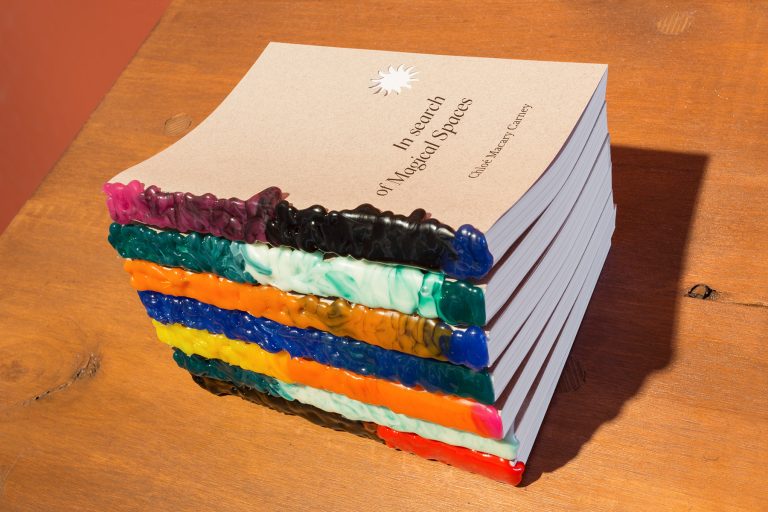

Everyone connects with stories I think, other people’s experiences, their way of retelling them, the surprising events that happened to them are so interesting and connect us to one another, it’s also how we learn. I remember stories much better than facts or news… At some point during the residency, I just had to find a format for documenting what was happening, and I didn’t want to lose the trace of the discussions I had with the people I met there, every day was so rich and full, that I started writing a journal of things that happened those days, without yet knowing what format the texts would take in the end. I didn’t know there would be this opportunity to do a solo show, to do a book, to have a budget to develop this project further, so when Júlia invited me to do the show, I started going back to the work I had done there, and there was a big work of reorganizing the texts I had written or interviews I had transcribed. In a way, the story is a bit non-linear because there were multiple storylines at once, with different people I met in Hungary, and when I was back home in Paris, I tried to interweave these stories in a chronological way, although that is not truly how these moments were experienced. Once I had that room to look back on things, I was able to put some sort of order in them. The format of the book also allowed me to fill in some parts of the story with visuals, photographs I took in Hungary but also found images which leave room for other stories or interpretations. It’s hard to explain with words, but I also really enjoyed how the book format allowed me to transcribe different formats of discussion that I had with people I was meeting, whether that be Facebook chat conversations, WhatsApp messages, Facebook posts or e-mails, when I started putting those discussions with different people in order, I found a humor in the timing of them, which adds meaning to the narration without proper words. I find that kind of funny to play with these online messaging formats of discussion because they are not instant at all since people can ghost you, ignore you, or answer you months later, and I put those non-linear formats into a chronological order which was fun to play with.

// /

The Tony Lavazza’s Sulphurous Pyramid Home exhibition was held at Budapest Galéria from 10 August to 18 September 2022. Curated by Júlia Hermann.

You can follow the Woman Cave Collective on Instagram.

Anna Keszeg is an associate professor at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design Budapest.