In flower language – Zsófia Papp’s clothing collection drawing on folklore

Folk art has permeated Zsófia Papp’s life from an early age, and even as a fashion designer, she often draws on traditional forms. Her diploma collection focused on bringing the principles and values of folklore and contemporary design into harmony, while lending a modern interpretation to motifs from Kalocsa through her own filter. We also talked about generational legacies and folk kitsch.

How would you briefly describe your collection “In flower language” to those who are not familiar with it?

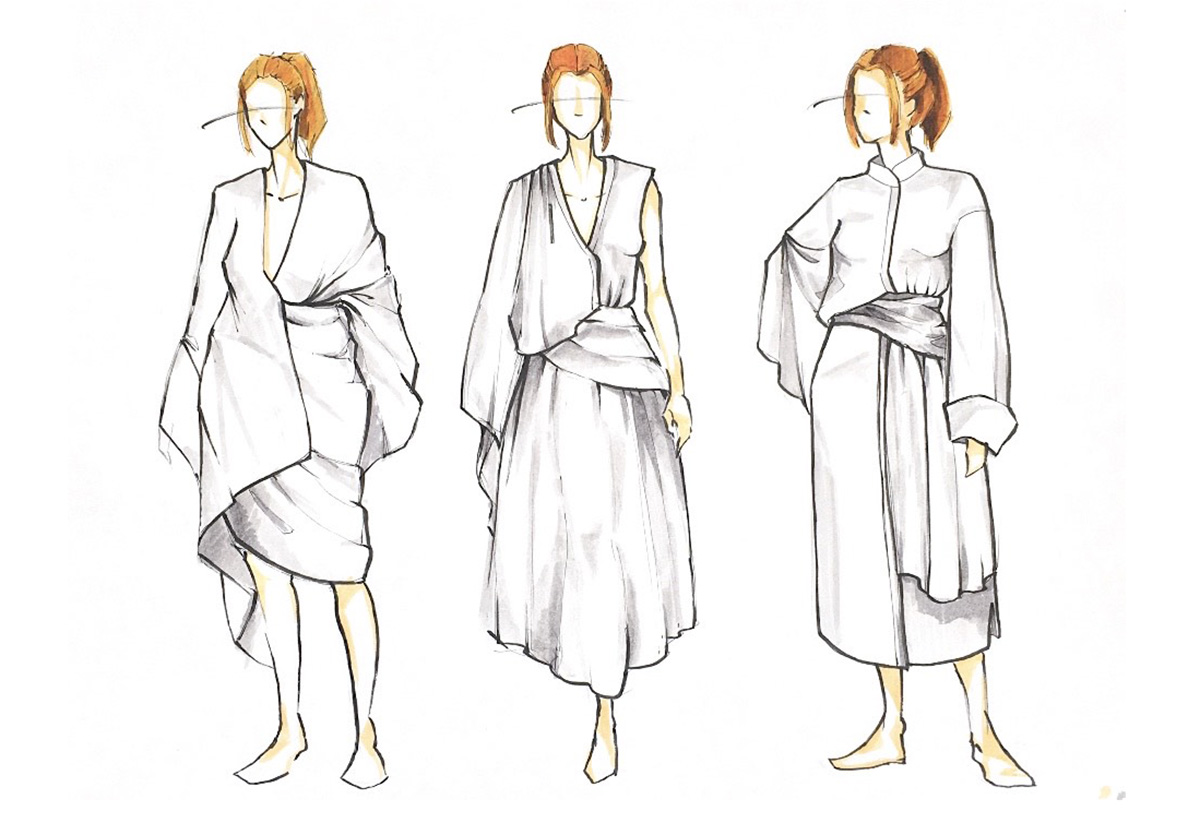

My diploma collection focuses on the cultural legacy encrypted in the code of folk art and formulated in flower language, as well as lending a modern interpretation to the values of folklore. The title of the collection is a reference to the messages composed using the natural symbols of folklore. These are universal truths that can still be relevant today. The floral ornamentation and wavy line are symbols of the flow and constant reinvention of culture, the unfolding of and periodic changes in life, which also signify the ancient and inseparable unity of nature and man, the spiritual and the physical world. Folk ornamental art in my opinion is a transgenerational legacy, an expression of shared identity. By understanding symbols and creating a contemporary interpretation I seek to find links between the values of the traditional and the modern world.

Can you tell us a bit about your history with folk art? I believe you have several connections to folklore.

I have a strong connection to folk art since I was a child. I folk danced for 20 years, which led me to experience folk art directly, and it was my love and respect for folk costumes that steered me towards fashion. I had experienced folk music, folk dance, the power of belonging to a community and the values of folklore in their original environment. It feels natural to me and it is where I feel at home. At the same time, I’m aware that folk art and its relevance are very divisive subjects.

Many people have no connection to it whatsoever, or mistakenly equate it with the tacky souvenirs sold by tourist shops, or nationalism.

This experience gave me a sense of mission to show the genuine beauty and politics-free values of folklore that are worth preserving and updating.

In recent years, your works as a fashion and textile designer have been continuously reflecting on folk traditions, so obviously the choice of subject for your diploma work did not come out of nothing. Can this collection be regarded as a sort of summary or culmination of your work?

When I was at university I found myself inescapably drawn to folk art for inspiration when searching for a subject for a project. No matter where I started, I would always end up there, and discover interesting correlations and parallels between current issues and folk art. This has become an important part of my identity as a designer during my university years. This journey has been far from easy, because it is difficult to satisfy both the conservative, traditionalist approach and contemporary design mindset at the same time. I’ve had a lot of internal struggle about whether there’s a point in doing it in fashion at all, and how to do it well. The choice of subject for my diploma work was determined by two important projects. During our Future Traditions semester, as a recipient of the New National Excellence Programme I had the opportunity to delve deeper into the folk art of a region, and explored the evolution of folk ornamental art through the study of motifs from Kalocsa. The other project was my work Reproduction, exploring transgenerational legacy and the reproductive role of women, as well as its expression in folklore. My diploma collection represents the linking of the two subjects, a culmination of the two projects.

What was the biggest challenge during the design process? Did you have any epiphanies beyond your professional experience?

Perhaps the biggest challenge was to summarise the experiences of the preceding years and to find inspiration without the outcome becoming overly general and yet representing a stance that I can build on even after graduation. In order to produce a clothing collection with such a clear concept it takes a lot of failed attempts first. Over the years, my idea of what is the “right” approach has changed a lot. The knowledge of authentic sources is indispensable for creating something new in this field, and you need to take the time to get a deeper understanding. My other epiphany was that critical review is necessary.

Because of my close ties to folklore, it will always remain a romantic, idyllic world to me. However, design and the development of folk art require critical thinking.

By applying a value-oriented selection process, you can retain what is still valuable today, and discard what is outdated.

The description of the work also underlines that a designer should not be afraid to explore traditions and the issue of cultural identity. You have created your own set of rules building on traditional resources. Could you explain the basic principles of your system, and your designer approach to the dichotomy of tradition versus innovation?

As a BA student, I was all about the rules. I had a more conservative approach, but after a while realised that these rules no longer had any relevance, and in order to keep folk art alive – not just replicate it and conserve it in its current state – you need to innovate, and “update” the rules. This way, you can relate to your own cultural identity and continue to have a sense of ownership for it still.

Like everything else, living folk art evolves generation by generation. Each generation uses its own filter to reinterpret its legacy.

Beyond a responsibility to adopt and use it in an authentic fashion, we also have an opportunity to manage this great wealth of knowledge as we see fit. Naturally, understanding the traditions is essential for this, and so is humility to prevent the rules from being clean broken instead of creating our own set of rules after gaining an understanding. My masterwork for example displays it by presenting folk symbols through the patterns of a given region. I layered versions of pattern treatments by the various generations on top of each other to create my own representation of patterns from Kalocsa. For my choice of colour I take the basic colours of embroidery from Kalocsa as a starting point, but in step with current colour trends I also borrow some of the more vivid and paler shades of the two basic colours, red and blue. In terms of forming, the method of folk dress making was the base, and though the details and tiny hints do echo traditional folk costume, the goal was not to reproduce it through and through.

In recent years we could see motifs of folk ornamental art featured on contemporary items and pieces of clothing to varying standards of quality. What do you think needs to be done to avoid producing a sort of national kitsch? Do you see this as a real threat?

There is a real risk, yes. A lay person can be easily mislead by the souvenir shop items.

Adopting folk art motifs just for decoration, without making any changes to them completely destroys the point of folklore.

Embroidery from folk costume used in its original form but taken out of its original context becomes empty and meaningless, and has no place in fashion. National kitsch is characterised by featuring folk art as decoration only on items and pieces of clothing. They adopt complete motifs from the ornamental art of peasant culture or the forms of our folk costumes, and even when adjusted to the contemporary taste they are not much different from the original. There are very few examples involving individual understanding and transposition to a unique aesthetics, like in genuine folk art. The aversion many people feel towards folk art is caused by its association with and appropriation by politics. Poorly executed fashion collections inspired by folk art don’t do much to help cure this aversion. Without the proper knowledge and humility, folk ornamental art grows empty. This is where the designer has a great responsibility.

Now that this chapter of your life is over, what next? Will you continue to produce works that draw on traditions?

Folklore can give you a lot to draw on, as well as answers to current burning questions of the fashion industry, such as the unsustainable pace dictated by fast fashion or the relationship between maker, clothing and wearer losing all meaning. The latter could be remedied by adopting the approach of peasant culture. Even if I stopped using folk forms as a direct source of inspiration in the future, I would still keep to the principles of folk clothes making, because I seek to use a more sustainable method of dressmaking.

// /

Zsófia Papp graduated from the Fashion and Textile Design MA of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. Her supervisor was Ildikó Kele, and her thesis consultant was Andrea Simon.

Photographer: Bálint Schneider