Co-creating with Machine Intelligence – An Interview with Lysandre Follet

AI-powered generative design is on the rise. Will we become curators of AI’s creativity? Will we design tools and systems instead of products? Will machines become creative partners or will they take our jobs? We have interviewed Lysandre Follet, an Industrial designer, Musician and Innovator, who has pioneered the use of generative design within Nike’s Innovation Studio. Lysandre visited Hungary to give a talk about the perils of AI-bias. We asked him about generative design, co-creation, modular tools and customization, among many other topics.

You’ve started as a musician and then became an engineer. You’ve built your career around creative technology and co-creating with machine intelligence. Could you please tell us, what inspired you to delve into the world of algorithmic art and design? How did you start off?

I have studied engineering and computer science, but at the time it was very rigid, which forced me to go back to my first love: art. Both of my parents are artists, so I decided to study design. Back in 2010, I started to see more and more people – especially architects – using computation and computer science as a creative medium through the lens of generative design. I found that intersection very exciting, so I wanted to spend my time researching and creating in that field. I was leveraging the machine to augment creativity, and I really started to understand how we can become creative partners.

What was your first project with machine intelligence?

I made some pendant jewelry. Those were really cool because I used mathematics, actually a simple equation to make some interesting shapes, and then I 3D printed them. I had a lot of early ideas of using digital manufacturing to produce something that was made by an algorithm. The execution was interesting too, because in the end you have a piece of gold or silver jewelry, and you would have never imagined that they were made by a computer. I like to play with the real world, so I haven’t made too much digital-only stuff.

These objects that can exist both physically and virtually seem to capture your imagination. You often use the term “hyper-real” and “hyper-creativity”. Can you explain them?

In the last few years, there are a lot of new dimensions, like augmented reality and virtual reality that you can explore as a creative. They are really fascinating, because you can create the illusion that something is there, but actually it’s not, it’s just augmented. Technology allows you to accelerate the process and make it more creative. So that’s why I call it hyper-creativity. Once you start to implement augmented reality as part of your workflow, you realize that you can see things that you couldn’t see before, and have an immediate connection with your design. It’s a completely different experience than looking at it on a computer.

Help us, what are the main differences between traditional and generative design?

In traditional design, you are often goal oriented. If you decide to design a chair, you sketch a chair or a couple of chairs, then let’s say you can build two prototypes. With generative design, there is a huge shift. You’re now working with a dynamic agent and there is not just one or two possible solutions, but there are an infinite number of them. Then you look at that solution space and start to explore it and understand what makes sense. You may just keep a subset of that solution space, but you have the potential to explore many different possibilities that were generated by the machine. On top of that, when you use algorithmic design, you build a model that describes the features of your product, and then you can use parameters to change these features. I can say that I want a chair with X legs. Maybe it doesn’t make sense to have a chair with 12 legs, but I can easily explore the idea, since I have a parameter controlling the number of legs. I can explore all those possibilities without even having to design them myself, because I design the system that designs the solutions.

It sounds like the workflow of product design has changed significantly in this new era of computational design. Do you think art schools now need to teach different skills?

I think it really depends on how much you want to be involved in the creation of the generative systems. But if you truly want to be the architect of the system, then you probably need to have a little bit of a different skill set. A lot of successful people in this field have a background in computer science, and they are able to code. Speaking the language of the machine is essential.

I also think that as a creative today, probably the most important skill you can acquire is being critical.

Now that anyone can have access to powerful technologies, anyone can make 3D photo renderings of an organic form with Dall-e, it is crucial to learn about how you assess something, how you construct a critical point of view. Many students are amazed by what the image generating AIs can do. It’s amazing, indeed, really powerful, but it’s better to be critical with them. Some people think that everything you create with these tools is new and interesting, they think it must be because it was made by the AI, but actually they are walking in an echochamber. They are under the illusion of novelty, while the system is directly forcing them into some sub-pocket of creativity.

You’ve mentioned earlier that designing with a generative system requires you to plan ahead, to see the sequence of variations necessary to arrive at the final solution. Is this possible with generative AI too?

Yes, it’s very similar to playing chess in a way that you have to understand the next move, while keeping track of the previous ones. To lead the way, you need to map the path by understanding where the system is going. Sometimes it requires trial and error, because you try to understand why something is interpreted in a certain way. Then you go back and modify the algorithm, until you start to get something that feels much better. That’s generative design. With generative AI, the problem is that you’re not the architect of the system. You’re using a system that is pre-made and opaque. If you open the hood of a ‘66 Mustang, you can see how it’s working – this is generative design. If you open a Tesla, there’s nothing to look at, it’s just a computer – this is generative AI.

And where do open-source systems fit in?

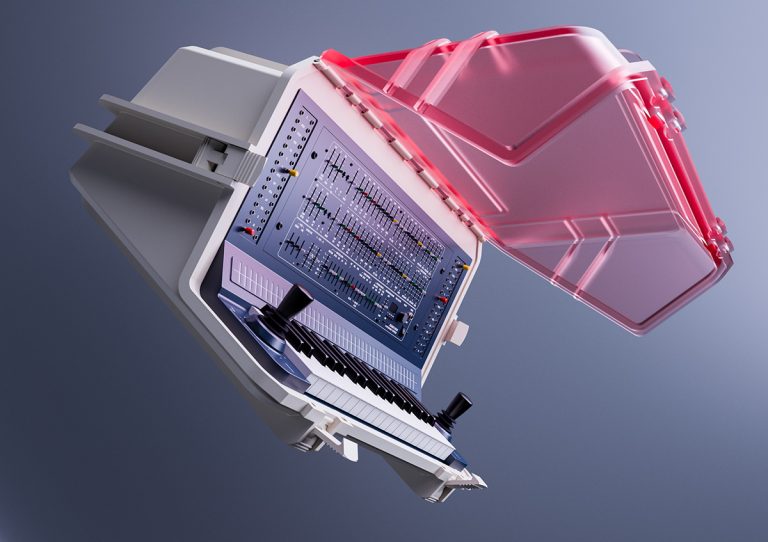

I think they will be the future. An open source system like Stable Diffusion allows anyone to build on top of the existing code. You, as a creative, will be able to combine these modules to create your own AI. The future is going to be modular. And this will be part of your secret recipe, because the way you combine them will make your work unique. It will be like modular synthesizers, where the idea of rewiring is fundamental. Allowing happy accidents to happen by combining things in a way that no one else does is what makes you stand out. Highly configurable algorithms which you can tailor to your needs, and use in a specific combination in a specific situation – I think this is where we are heading now.

You like to quote Engelbart who said that “A tool doesn’t just make something easier, it allows for new, previously impossible ways of thinking, of living, of being.”

I love that quote because it refers back to craftsmanship. Good craftsmen – for example the carpenters in Japan – often build their own tools. They build a tool that has never existed before, because they try to achieve something very specific that requires that specific new tool. So the idea of being a tool builder as opposed to being a tool user is very important to me as a creative. If you stay a tool user, that’s fine. But eventually you may find yourself doing the same stuff as everyone else.

Every tool forces the user into a certain defined aesthetic.

But if you become a tool builder, you will be able to customize things much more and achieve a new, unique domain of creation. Brian Eno or Aphex Twin are great examples, they build their own systems and instruments to explore generative music for instance.

At Nike you have a group of talented people working with hi-end equipment. But how feasible is the generative method for individuals who don’t have access to a lab and a research team?

When I started pioneering this field 11 years ago, it was very elitist. You had to have the expensive hardware and specific skills. Today, the landscape is very different. The tools have become much more accessible and democratized. You can find many open data sets on the internet and use them in your model, so I think there is a way to at least get going, until you need to do your own research eventually.

In your work you often use biological, natural forms as a starting point of the design process. We have seen designs inspired by planktons, corals, slime mold and magnetic fields. Is there something about generative design that favors these organic forms?

We find inspiration in nature, because evolution has created very efficient solutions for certain problems. It had to be efficient, otherwise the organism went extinct. A lot of the problems we are trying to solve are universal. For instance, we look for a structure that is stiff and light at the same time. We try to find how we can tune stiffness while maintaining the lowest weight possible. Nature is doing these things very well, let’s just look at a beehive or the shell of certain planktons. Planktons need to be light, so they can travel easily, but also stiff and resistant, so they don’t collapse under high pressure. It makes sense to turn to these systems and not try to reinvent the wheel. We use organic forms for the structural properties and not just for the organic look.

Generative design often looks natural and organic even without the input of any biomimetic data. Why is that?

When we build these algorithms, we use a mathematical (a physical) framework that describes reality through equations. Magnetic fields, for instance, are phenomena we see in the real world, and over a century we’ve understood the equations, so we can use those equations in our generative systems. Creatives have always been fascinated by nature, because it’s so complex and so beautiful at the same time. When you look at those seashells, you see how beautifully they are designed. It looks like everything is aligning perfectly, blending from one shape to the other. So this is kind of an obsession; we are trying to crack the code of beauty in nature.

On top of that, some things are almost impossible to do with traditional design, but they are possible with generative design, because you can leverage computation to create something very complex that emerges from simple rules.

Take phyllotactic spirals for instance, those beautiful spiralling organic things that you can see at cactuses. Phyllotaxis is actually a simple equation, which is hard to calculate by hand – especially if you want to apply it to dispersing LED lights for example – but you can calculate it in seconds with the algorithmic method. I think a lot of people are obsessed with natural systems for a good reason. For the first time, we are able to recreate and utilize these systems as part of the design process.

At Nike you tackle the problem of customization. AI assisted designs work best if they are recalculated/mutated, not simply scaled up or scaled down for given sizes. Do you think with more algorithmically designed products available, there will be a revolution of customization in mass production?

For sure, generative design is the tool for mass customization, because it’s parametric. If you change a parameter, the algorithm recalculates the solution, and the result is a different structure, not just a scaled version of the original. Currently, the problem is on the side of manufacturing. Unfortunately, it’s not possible to 3D print at large scales yet, so for now, the bottleneck is manufacturing. At Nike we’ve proven that we could print custom variations, and they were performing just as well. But is it viable to print for you? Maybe not, because the shoe will cost 2,000 dollars. But the cost will decrease over time.

Let’s turn to a popular question. Many people see AI as a threat because of the possibility that they may lose their jobs to algorithms. What would you say to them?

Well, we’ve seen over and over that jobs disappear and new ones get created. If you think of a social media manager, it wasn’t even a thing for our generation. Now, there are many people who make a great living out of it, to the point that almost every kid wants to be a social media manager. I think a lot of people are going to lose their jobs, but it’s important to understand that upskilling, especially for our generation, is probably the way to go. You have to constantly be aware of the new trends, learn and use the new tools and understand how your field advances. Our parent’s generation has often worked 40 years in the same job, but younger generations almost have to reinvent themselves every few years. I think this is especially the case with creative jobs. If you’re missing out on learning new technologies, people who use them in your field will perform better. But I don’t think you should fear losing your job. You should ask yourself the question: What do I want to do next? But everything I’m talking about is within the realm of industrial design, so I’m not talking about artists.

You’ve brought an oil painting to MOME that was painted for you by an artist, but the original image was generated by Midjourney, a text-to-image AI. Would you still value this painting if it was created by machines without any involvement of a human?

Yes, I’m fine with the whole spectrum to be honest. I really enjoy analogue art, and I really enjoy purely digital stuff. What I don’t enjoy is when there is no reasoning, there is no act of creation that goes into the process. A lot of students ask me what they should put in their portfolio. For my generation, the portfolio was mostly renderings, because that was the trend, where the money was. Today, if a student comes to me with just a few renderings, how do I know if the person is competent? I don’t want to hire someone who just used Midjourney. I want to see the process. So they would have to convince me through documentation that is much deeper than the output. I want to know what their thought process was to create that piece.

If you cannot explain why the image looks like that, it means that you do not have agency, the system created it, not you.

That’s what I love about good art shows: our museum often explains a little bit about the space the artist was creating in, about the journey, about the story of a piece. That’s part of the beauty. I hope that a new format will emerge which will let us learn more about the process, something that is more than just the visual output. It may encapsulate timestamps or something else that would allow me to see the creative process.

You also build eurorack modules (a modular synthesiser format). How do you see the future of electronic music? Will algorithmic, AI-assisted ways of sound design, composition or performance become more prevalent?

Yes, I think we are going to see a lot of fascinating things in music. For instance, building not just one piece of music but something that can take on different paths based on the circumstances – songs that are not static but can adapt to the environment. Just like video games that have procedurally generated worlds, where the map is never the same twice, but every variation has the same DNA, the same feel. One of the guys who co-founded Google Maps, made a startup to create music that can take different paths. It’s very interesting to see that if you come back to a certain song – and for instance your heartbeat is faster – then the track will adapt. There is an embedded intelligence to it. So the more you listen to that track, the more variations you can explore. If you think about our world, it’s never the same twice, there are always subtle variations. So far, we have been living in an environment where everything made by us was more or less in one fixed state. But now we’re moving towards a world where our things are becoming more adaptive and are evolving to reflect the nature of the world around us. Nothing is static in reality.

// /

Lysandre Follet’s webstite: ?

Dávid Csűrös is a PhD student at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design.