“My goal was to create an opportunity to talk without shame” – Interview with Éva Szombat

At my first therapy session, after informing my therapist between two shaky breaths that I have no idea what I was doing there, she replied with a smile “Everyone comes here because they want to feel a little happier”. At the time I felt this conclusion to be depressingly simplistic and banal. Yet now, three years later and after learning slightly more self-awareness, I know precisely how much work you need to put in to realising a wish like this. It is precisely this constant and the diverse process of searching for happiness that Éva Szombat’s photo series confront us with. We asked the photographer about her earlier works and her photos I Want Orgasms, Not Roses, recently published in a book and also featured at an exhibition.

According to your credo, you enjoy exploring how to feel good and maintain a healthy level of happiness in our lives. In light of the global adversities of the past two years, we need this life-affirming attitude more than ever. As a creative person, how successful were you in maintaining this approach?

I had a pretty rough start to 2020. On top of COVID, my dad passed away in March, and that left its mark on everything. It was the first time I lost someone this close to me and felt such devastating grief. It hasn’t been the easiest time for me, but it’s alright. If you were constantly happy, you wouldn’t realise you were.

I think we’re often happy despite something and not because of something, and perhaps that’s why it feels so fleeting.

I also consider this to be a typical Hungarian attitude. Here we don’t like to flaunt our happiness, rather tend to bond over complaining. This was also the inspiration for my Happiness Book. I was very annoyed by the constant effort to outbid each other and see who has it worse or who’s to be pitied more. Before I started working on this ironic ‘textbook’ composed of built worlds, a friend of mine, Olivér Artúr Kovács remarked how happiness is like Math – you need to learn how to do it. I liked this insight so much that I turned it into the epigraph of the book. My later series, the Practitioners used real-life situations and case studies, arriving to the conclusion that we tend to forget how to be happy, which is why it’s not enough to learn it once, we need to be able to re-learn it.

Photos from the Happiness Book series (2014)

It was precisely your Practitioners which got me thinking about the creative tools in your palette – kitsch, glamour, and irony. In addition to incorporating them into your series, you also drew heavily on classic report photography codes.

Exploration of the roots of photography brings us to the relationship of reality and fiction. Early on, we are taught that the aesthetics of report photography is somehow closer to reality. My pictures, however, always have surrealistic elements mixed in them that unsettle and confuse the viewer. Abraham A. Moles calls kitsch the art of happiness, and I feel attracted to this flamboyant, brilliant and colourful aesthetics.

I often have the feeling that I need to fix whatever’s wrong and give it a more acceptable and fancier packaging.

I was a late child and grew up hearing “what happiness a late child brings”. So I keep searching for ways to become a bringer of such happiness, and perhaps this is what lies behind my research and photos.

With Practitioners however, I was forced to change my creative method, because that project was about something different. The goal here was not to create a fictitious world, and so the pictures are more closely linked to reality, despite incorporating elements of strangeness every now and then. Just like real life, which is also full of situations so absurd not even a screenwriter could come up with.

Photos from the Practitioners series

Practitioners feature people who are able to find happiness again and again after overcoming the most difficult situations in life. Your series Tutti Frutti represents a similar rediscovery of happiness, this time as a companion to nostalgia. That’s why I was wondering if it was genuine happiness we’re talking about or rather an escape from anxiety.

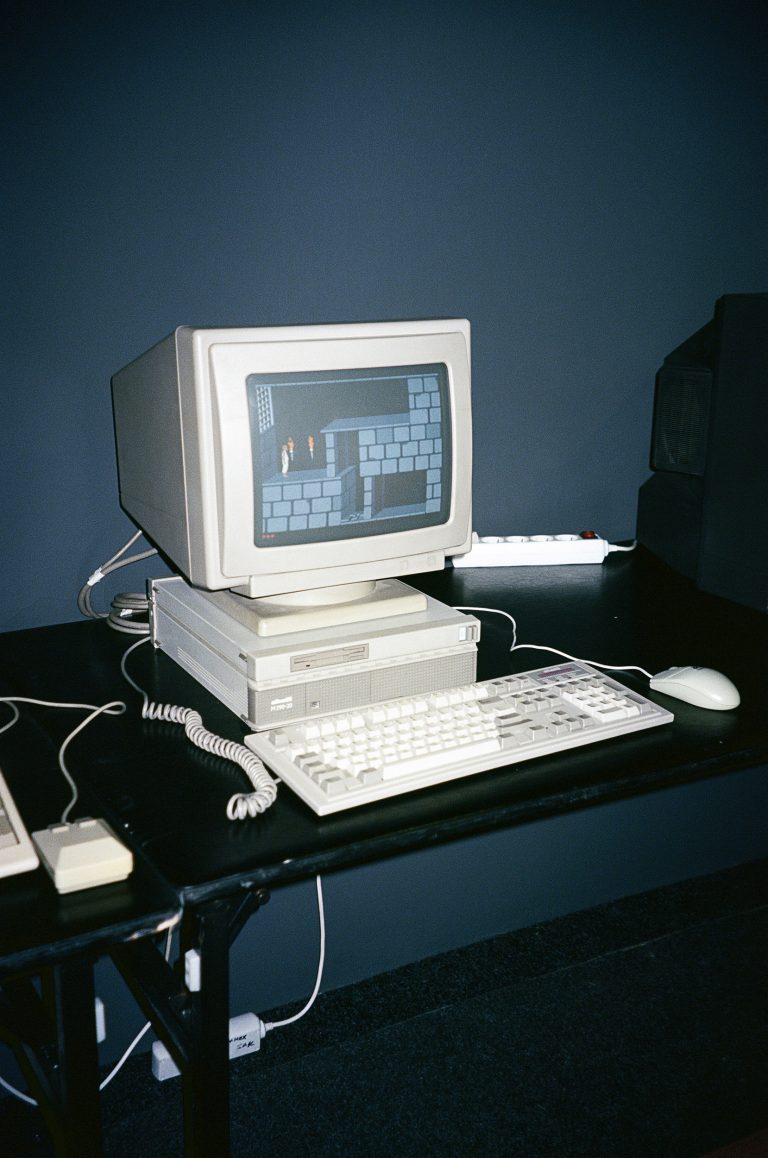

I reckon it’s more about escape too. During the pandemic, many people described how in difficult and uncertain times we tend to start longing to be back in the past when everything was still alright. It’s an interesting philosophical question, because there is something utterly backward-looking in this response. When I was struggling with loss, I turned to the music I listened to as a teenager. Yet my Tutti Frutti series also dealt with young people who felt drawn to periods they did not experience. This is all the more peculiar as they are hanging on to an idealistic age only existing in their imagination rather than experience. In addition, there is another observation related to my own age that I find intriguing. I started making this series at age 30 and that’s when I noticed that a period I’ve already lived through is slowly making its way back into fashion. At first the idea that something that used to be cringey is now trendy made me feel uneasy. At the same time, it was exciting to see a bygone period gain completely new meaning. How desirable or not this trend is remains a question though.

Photos from the Tutti Frutti series (2017-2020)

While Tutti Frutti embodies escape into a safe past, Beyond the Curve represents the vulnerability of open confrontation with yourself through the lens of a camera. What did it feel like as an artist to watch your own reactions and searching your heart for the happiness that comes from self-acceptance?

Though what you say about vulnerability is true, at the same time I also feel that after a step like this you simply cease to be vulnerable. If you no longer have anything to hide, you cannot be hurt any more. I also started working on this series when I turned 30. That was the year I got married and when all the expectations around this and my age caught were sprung on me at once. I’ve been struggling with my weight all my life, and it was around this time I began to realise that having the slim figure so many people long for isn’t necessarily the same as having a healthy body. Ultimately, the project was about seeing what happens if I accept myself as I am. Which would obviously be a tremendous accomplishment, especially for someone who struggles a lot with their body image. I simply refused to have my whole life revolve around this. I have better and worse days in this respect too, but after all, self-acceptance is also something you need to keep practicing.

Photos from the Beyond the Curve series (2017)

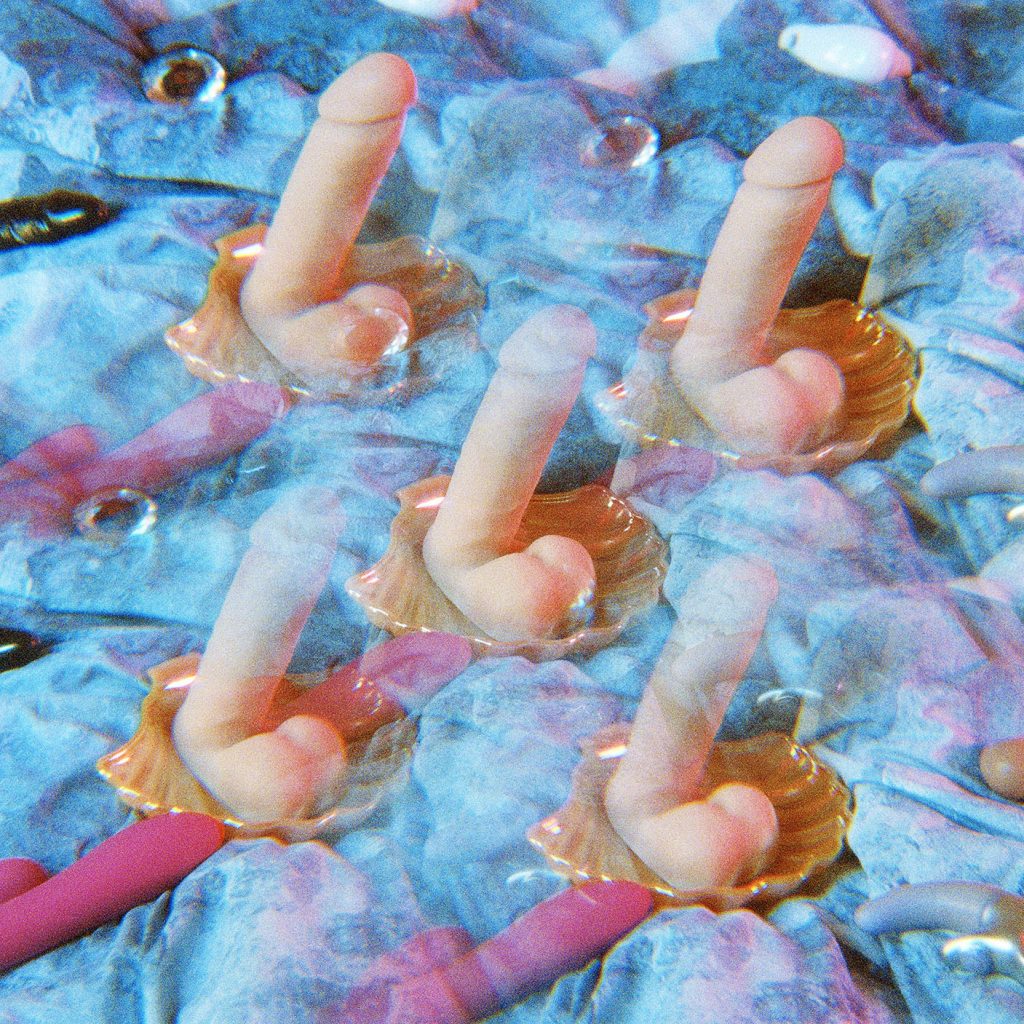

After the tightening of the abortion regulations in September 2022, the relationship we have to the female body has never been more relevant. This is where your project I Want Orgasms, Not Roses, which was awarded the Capa Grand Prize in 2021, comes in. It explores female sexuality, which, despite being a natural and organic part of our lives, is still considered a taboo. Your series was featured in a publication that made its debut at the Paris Photo November last year, and now at your solo exhibition in Longtermhandstand Gallery. How was your scholarship experience, and how did the final material for the series come together?

I started working on I Want Orgasms, Not Roses in 2017, and after I received the Capa Scholarship in 2020 I still had another year to finish it. It was a great opportunity to be able to fully focus on it, and winning the Capa Grand Prize was also a great experience. By the end of the scholarship term, the material all came together nicely and received very positive media coverage after the Grand Prize. In 2022 I went over it again and tweaked it around, but that year was mostly spent turning the dummy book I made during my scholarship term into a publication. We did the layout together with graphic designer Anna Bárdy, and the publication was issued together with the German publishing house Kehrer and Everybody Needs Art . So this book is chief form the photos take, while the Longtermhandstand exhibition is the platform accompanying the project, enabling creative communication about the subject through various media such as a flag or a bed installation.

Photo from the I Want Orgasms, Not Roses series (2017-2022)

Of course the photos are also important on their own, because by showing their sex toys in their own bedrooms, the women on the photos initiate a sort of removal of taboos and a discourse. However, for the project to be regarded as complete, the interviews made during the photoshoots also need to be incorporated. When the project was launched, these photoshoots started out rather funny, but the more we talked to participants, the more similar frustrations and obstacles came to the surface. That’s when I realised the severity of the issues explored here.

After all, what leads a woman to respond to a call and show her sex toys?

And why are female desires and female orgasm still an awkward and unpleasant subject?

I think these issues result from communication inhibitions around inherited transgenerational patterns. My goal was to create an opportunity to talk without shame.

Telex’s documentary about the BDSM subculture premiered not long before the opening of your exhibition, providing insight into another segment of sexuality treated as a taboo by society. These initiatives always spark off intriguing dialogues, whether in broader or narrower segments of society. In your experience what questions and reflections do people have about your series?

I also found Telex’s documentary invaluable, and it also features one of the people in my book. It is precisely the sort of initiative that is needed to start a discourse. I got some fairly mixed feedback on my project, as is only natural with a subject like this and I was prepared for it. Earlier press cover ages of the series were also largely due to its highly controversial nature. Of course, politics also plays a role here – nowadays, it has become trendy to talk about the female body only in the context of giving birth, and the abortion act also tips the scale in favour of this. There were also some overwhelmingly positive reviews. I was told by many people how great it would have been to have a book like this when they were teenagers, or how much better off they would have been to realise they can talk about their desires even before hitting their 40s. These responses all confirm the need for projects like this. As for the provocative title, however, I’ve heard from several people that they found it revolting, or they thought there were more important issues than female orgasm. That may be true, though being able to and having the courage to talk about their desires and needs would definitely add to people’s quality of life. Having a good time in the bedroom can positively affect other segments of not just their own, but other people’s lives as well.

Photos from the I Want Orgasms, Not Roses series (2017-2022)

A girl in my book, Zsófi, for example described her aids as development toys that provide her with the opportunity to experience physical pleasure over and over again. I reckon there are few things that are more symbolic of female sexuality, pleasure and autonomy than a vibrator for instance. It makes you wonder how in some countries, these toys are banned or are more strictly regulated than guns. It is also telling that the same regulations do not concern the sale of Viagra, which is clearly classified as a drug used in healthcare. We tend to forget that vibrators too can function as a healthcare aid for some conditions such as anorgasmia (absence of orgasm), to help achieve climax. There are also people living with vaginism, and freshly transitioned trans girls, and they too have a range of sexual aids available to them. So these items definitely contribute to the maintenance of female physical health.

Yet while the male existence is automatically associated with the need for experiencing sexuality for a happier and more fulfilled life, the importance of the same for women is not often voiced.

Yes, while women are often reproached for not feeling up to having sex, the sexual act only lasts until the man is finished. The key question – why women don’t enjoy sex – remains unraised. We are conditioned not to speak out. This is precisely why finding my grandma’s scrapbook from the 40s with life advice from girl friends had such a profound relevance for me. All the messages reveal that you as a girl must endure pain and suffering, and will only be appreciated if you are gentle as a lamb. The burden of silence, passed from generation to generation, explains to some extent people’s decision to stay in bad marriages and accept it as their fate.

Through my grandma I understood why I sometimes find it so difficult to talk about my desires. I intend this book as an aid to help collective thinking.

By being exposed to photos with people who are open about their fantasies and toys, we can broaden our collective knowledge and normalise different forms of experiencing sexuality.

Do you have plans for continuing this series or rather move on to a new subject?

I believe that this project is complete. However, I am doing research at MOME Doctoral School on an ongoing basis, partly in relation to this subject. At present I’m interested in the workings of sex positive communities, such as what the group dynamics is like and how it affects individual sexuality. Slowly we might perhaps see a discourse emerging on this subject as well.

// /

Éva Szombat’s exhibition I Want Orgasms, Not Roses is running until 10 February at Longtermhandstand Gallery. Her photobook bearing the same title is also available there. Éva Szombat is a teacher of Photography at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design and a student of the Doctoral School.