Taking a stand through art – Interview with curator Veronika Molnár

She organises exhibitions, manages a gallery, authors publications, and is very much at home both in Budapest and New York. She even found the time to talk to us between two meetings and before a trip. After receiving her Design and Art Theory BA from MOME, she was plunged into the contemporary Budapest art scene as a curator. In 2019, she moved to New York to study at Hunter College. Despite choosing to return after an intense two-and-a-half year there, her projects and plans for the future are fundamentally defined by her overseas experience.

Though Budapest is by no means a quiet little town, relocating to that cultural global metropolis seems like a major shift in scale. In a previous interview, you have already talked about New York. I’m specifically interested in your experience of the local art scene.

Interestingly, the art scene in New York is much smaller than it seems at first – I began to grasp this after spending about a year in the city. Partly due to my Fulbright scholarship, I found myself in a very supportive professional environment and could meet with most of the artists and curators I reached out to. It was inspiring to see how the “Time is money” attitude embraced by the city is offset by the care and support of people in smaller communities who show up for each other in important moments and promote each other’s exhibitions on social media, for example. In most conversations, and not just with fellow professionals, people always looked for ways to help me and connect me with others, which made me feel welcome in the city.

During your stay in New York, you were involved in organising exhibitions of the Department of Media and Performance as part of MoMA’s internship programme. What is the curatorial workflow like at such a mammoth institution, and what was your role in it?

Perhaps it’s easiest to share a bit about a specific exhibition I helped organise. Adam Pendleton’s solo show, Who is Queen? opened in September 2021, but the museum began the initial conversations and planning in 2014. Pendleton’s monumental multimedia installation was particularly unique because it consisted of new works commissioned by the museum specifically for the MoMA Atrium. During my internship, I was involved in the last phase of this process, assisting chief curator Stuart Comer. It was inspiring to be part of such an ambitious project; to realize Pendleton’s vision without compromise required constant navigation of rigorous museum policies and deadlines. The installation process alone took three months and involved working with an architecture studio and a fabrication company. In addition, a podcast series and online film screening were also produced during the exhibition – the latter of which was my responsibility. Partly perhaps because of the downsizing due to Covid, I was given greater responsibilities than a regular intern, which made me feel like I was an active participant in nearly every aspect of organising the show..

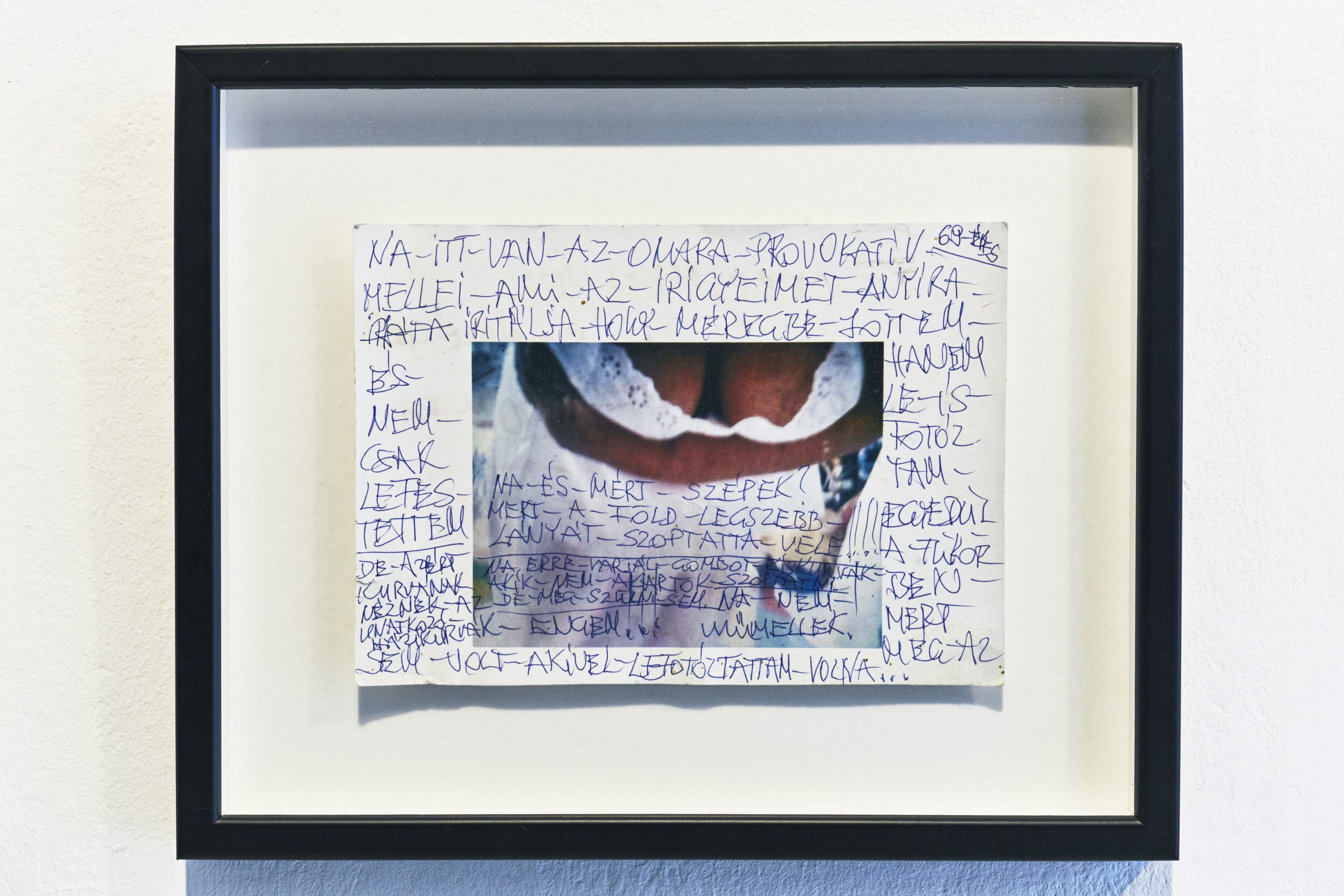

Oláh Mara OMARA: “Here-are-Omara’s-provocative-breasts” (2014-16), ball-pen on photo

Though your internship is over, you are still affiliated with the museum as an author. In January this year, your essay on Omara’s oeuvre was published on MoMA’s post: notes on art in a global context page. Large western museums are deliberately seeking out art from the peripheral regions and incorporating it into the global context they stand for. At the same time, the question of whether this marginalised state will truly come to an end, or Central Eastern European art will continue to be perceived as a freshly discovered exotic curiosity within the global institution keeps coming up, mainly as a result of decolonisation efforts. Having experienced a different cultural scene and the workings of MoMA close up, what are your views on this?

Whether central or peripheral art, I think bridging the gap between various cultural, social, and linguistic codes presents a major curatorial challenge.

Whether it’s about introducing Eastern European artists in New York or Southeast Asian artists in Budapest, it is important to strike a balance between presenting the original environment and leaving room for individual interpretation.

Reflecting on this issue, I drew a parallel in my essay between Mara Oláh’s art and the guerrilla performances of American conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady. I believe both challenged the art establishment of their time in truly innovative ways and resisted all attempts at their art being “bleached.” Not for a second did they consider toning down their style or behaviour to please the majority white audiences. This is where the concept of opacity in Édouard Glissant’s book Poetics of Relations ties in. It means that rather than overexplaining things, we accept the existence of contexts that are impossible to translate and convey one-to-one otherwise, they would lose their essence. Last year at documenta 15, for example, I saw no common thread running through all the works or a standard curatorial text, which sometimes made me feel lost. On the other hand, thanks to the ample room for free interpretation, I formulated many generative questions for myself.

The Strategic Stillness exhibition organised by you at the American Hungarian Library explores transplanting artworks with unique contexts and codes into a different cultural environment. Your exhibition concept also addresses the book shredding scandal surrounding A Fairytale for Everyone (Labrisz, 2020) featuring marginalised groups. How was this subject so deeply embedded in Hungary’s internal politics received in New York?

The American Hungarian Library was renovated just before our exhibition, which meant we could experiment with empty wall-to-wall bookshelves with the artists Judit Kis, Tamás Ábel, and Jacob Kassay. For the duration of the exhibition, we filled the library with new books that were either closely related to the research conducted by the artists or were proposed by various NGOs and members of the professional community. This is how Gay Men Straight Dictatorships ended up on the shelf alongside Living a Feminist Life bySara Ahmed. One of Tomi Ábel’s artworks featured in the exhibition reflects on the situation of the Hungarian LMBTQ community by displaying a copy of A Fairytale for Everyone wrapped in rainbow-coloured foil. He had printouts of Dóra Dúró’s infamous hate speech, which visitors could destroy using a shredder, resulting in a growing heap of paper waste that formed part of his participative installation. Around two hundred people showed up for the opening, which was a great experience. I felt that the subject resonated with the locals shortly after the Trump era.

How do you think all that practice you accumulated there affected your way of thinking?

My Master’s programme was formulated to be less Eurocentric than what I have been accustomed to in Eastern Europe; though there was a special emphasis on the New York art scene. This way, I could experience being profoundly moved by artists and theorists coming from entirely different cultural backgrounds and contexts from mine. Overall, I learned to become more open-minded and not to judge someone just because they think differently. Another important impression resulted from the way the city worked: streets and public spaces in New York strongly reflect social movements and processes. In Hungary, this sort of communication is less common, and contemporary art is less likely to take to the streets. Though this year, the 1st Biennial of Contemporary Art in Public Spaces in Budapest will take place, so there might be some progress in this regard.

You moved back from New York a year ago. In light of the experience you gained there what did it feel like to slip back into the cultural scene in Budapest?

It was challenging to find my place. Seeing how much the situation changed while I was gone was shocking. When I moved back last year, I felt that if I wanted to work with art in Hungary, I’d need to do it independently of state funding. The division between people is less clear now, which makes me feel like I’m navigating a minefield, never knowing when I take a step out of turn. At the same time, exciting events are taking place in Budapest, though not necessarily organised by the already embedded art institutions. I’m trying to keep a tab on what Trafó is doing for example. Last autumn, they put on two exhibitions curated by Judit Szalipszki and Flóra Gadó with longer titles…

Yes, Judit Szalipszki’s exhibition was entitled How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed? andFlóra Gadó’s was called I hold the table with my hands instead of the broken legs.

I think both titles reference the feeling of weariness that marked 2022. I see a sort of resignation in the Hungarian art scene, so I’m consciously building a small circle for mutually supporting each other. I think there’s a great need for these micro-communities to clear hurdles like that.

These two exhibitions sought to answer the questions of how community strategies can help and what retention systems are in place in everyday life.

It is crucial to look at how we can look after and help each other using our resources.

I feel that there is currently a lack of grassroots, independent initiatives in Hungary for supporting each other in a network organisation format.

Of course, the Studio of Young Artists’ Association is a positive example, though it provides opportunities less to cultural managers, curators, or art historians and more to artists.

You received the post of artistic director of Liget Gallery in autumn 2022, and it was symbolically granted to you by Tibor Várnagy on 1 March at the opening of the exhibition Unveiling organised by you. Has it always been an ambition of yours to manage a gallery?

I feel like the job posting was a sign sent by the universe because the position suits me very well. I have prior experience managing the Faur Zsófi Gallery, but I’ve never experienced the creative freedom and independence that leading a non-profit place can provide. Liget Gallery has practically everything important to me professionally. It is an independent, experimental exhibition space open to intermedial ambitions and emphasizing women artists. Perhaps the only thing I miss is teamwork, though I already have a superb assistant, Hanna Claris, so the two of us will be running the exhibitions in the future. Directing a gallery is a milestone that takes longer to achieve in New York, and in this respect, moving back to Hungary proved to be a positive development.

Reading about the current exhibition’s theme, I was reminded of FERi Gallery closed in 2021, where you previously worked as a gallery assistant. To what extent would you like to follow the same line, and how different are your plans for Liget Gallery? What other existing role models do you rely on?

In this regard, I surprised myself as well. Even though feminism has always been a fundamental framework for my thinking, and I loved working at FERi, a couple of years ago, I didn’t think I would have to foreground it to this extent in my practice –. But lately, this sense of going backward in time has been growing stronger – just think of the restriction and elimination of the constitutional right to abortion in Hungary and the USA, or the brutality of the Iranian morality police. What is happening at home and all around the globe right now convinced me that taking a stand against women’s oppression through art is more important than ever.” In addition, it has been part of Liget Gallery’s DNA from the very beginning to support women artists. So, this is an ongoing mission originating from both FERi and Liget. But I’m also influenced by other positive impressions from various other workplaces I’ve had, which is why I would also like to introduce ecocritical artists, and there are plans for collaboration with a larger NGO that would draw a different audience to the gallery. I would like to create an atmosphere enabling artists and projects to reflect actively on political events.

Magdalena Frey, Mutterkuchen (1989), detail, digital print

I believe the current exhibition has also sparked some intriguing discussions…

Yes, perhaps the exhibition’s most polarising work of art is the photo collage Mother’s Cake (Mutterkuchen) by Austrian artist Magdalena Frey, first displayed at the Gallery in 1993. Though this exhibition features only one section of the work composed of four tableaus, even after 30 years, it hits you hard. She documented her own pregnancy and the birth of her baby in a naturalistic fashion, demonstrating a sort of “medical gaze” as a result of her qualifications as a nurse. At any rate, it was an incredible experience to hear four men with little familiarity with contemporary art contemplate the photo after a guided tour. They started discussing their delivery room experiences including what severing the umbilical cord felt like, or to what extent being present during childbirth can strengthen the bond between father and baby. It is greatly inspiring to see a work of art prompting viewers to open up to this degree.

Beyond Liget Gallery’s events, what other projects can we expect from you in the near future?

In addition to managing the gallery, I also work for Walter’s Cube , an art and tech start-up, experimenting with presenting exhibitions in digital twin spaces. We are just launching a collaboration with the Secondary Archive and the IKT International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art; this will be our big project for 2023. Additionally, I will participate in a curatorial residency at Residency Unlimited in Brooklyn with the support of the Bubu Programme led by Katalin Mechtler in May. I am conscious in my efforts to stay connected to the art scene there as I’d like to build more bridges between New York and Budapest in the future.

// /

Veronika Molnár’s website is available HERE!

Portrait: Róbert Balogh

Photos: Veronika Molnár

Interior pictures and reproductions: Áron Wéber