“Irony is useful for asking critical questions”

Viktor Varga’s masterwork Beep-boop is quite extraordinary, to put it mildly. At first glimpse, it appears to be nothing but a floppy, poorly cobbled together contraption clamouring for attention that seems rather far from standing out in any way. That being sad, from this year’s graduating students, Viktor has been selected as one of the four Rector’s Award recipient, and not without reason. Once we put some time and effort into analysing his work in more depth, we find ourselves dealing with an intriguing project with many layers to it exploring current issues that are no doubt relevant for all of us. 100 hours of machine learning, 14,500 users, optimisation, artificial intelligence, art creation – and a large dose of irony. We talked to Viktor Varga about his work.

In the description, you cryptically alluded to maximising attention. What does that mean in reality? The installation is showing off, while a software is monitoring eye contact?

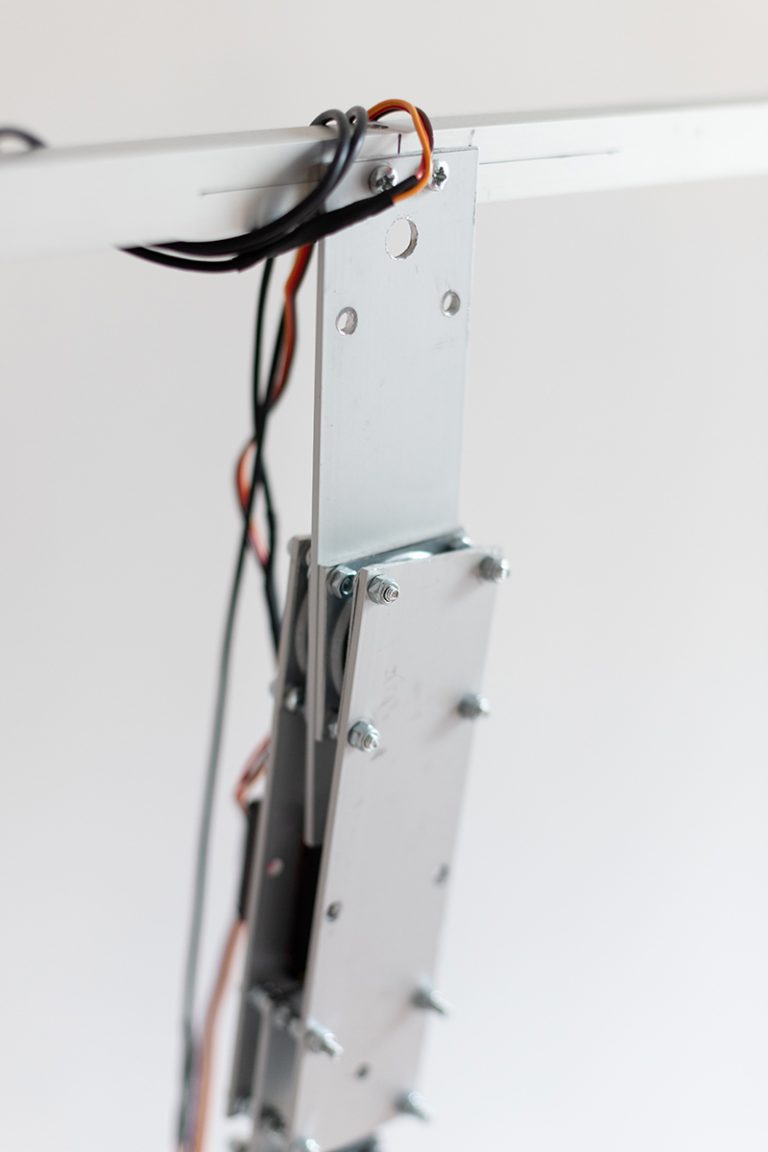

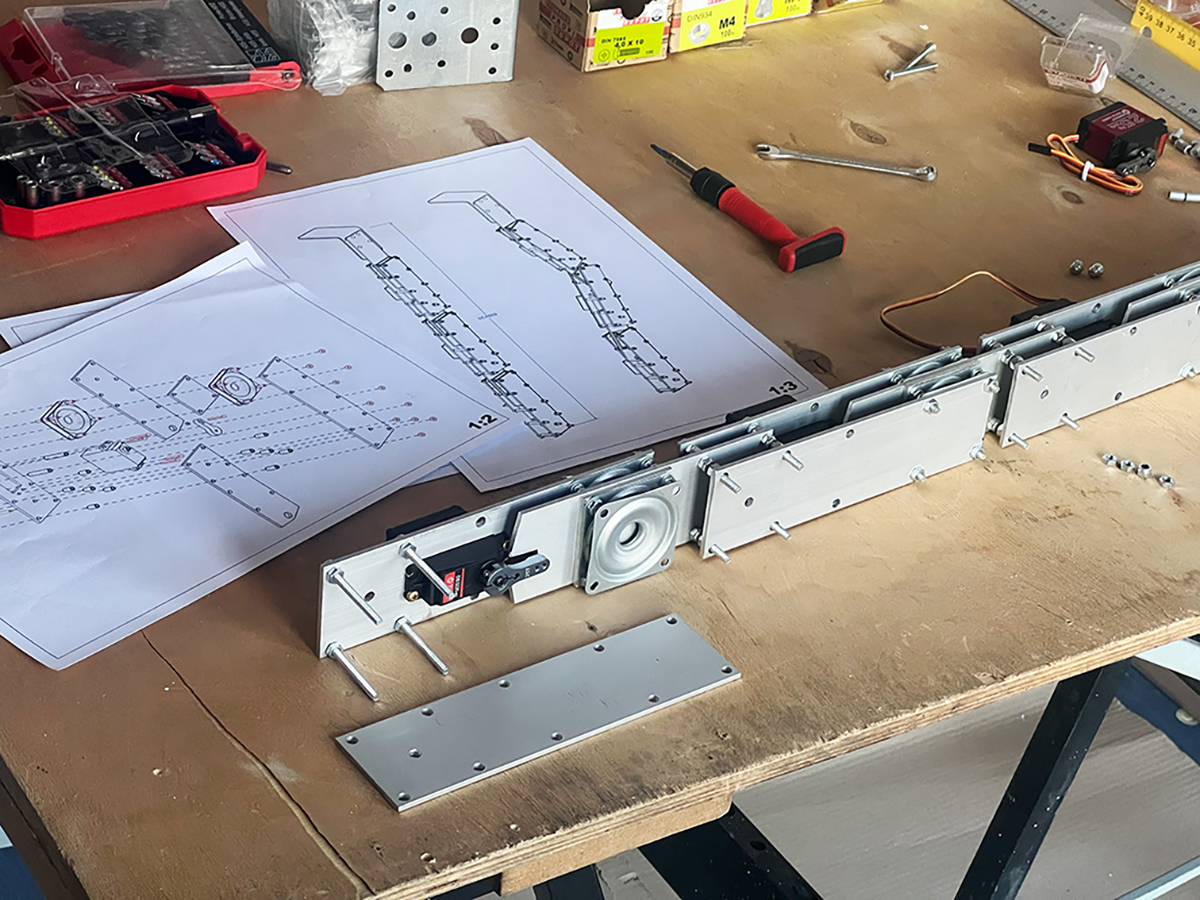

‘Showing off’ is a great way to express what is going on with the installation. The simple motion of the contraption is determined by a combination of three numbers. The system tries a random combination (that translates into a certain movement), monitors how much attention it gets, logs it as a score, then repeats the same sequence with a different combination, only the probabilities are gradually shifted towards combinations that previously received higher scores. This way, a learning process is being developed, repeating behaviours attracting a lot of attention with increasing frequency and consistency.

And what about eye contact?

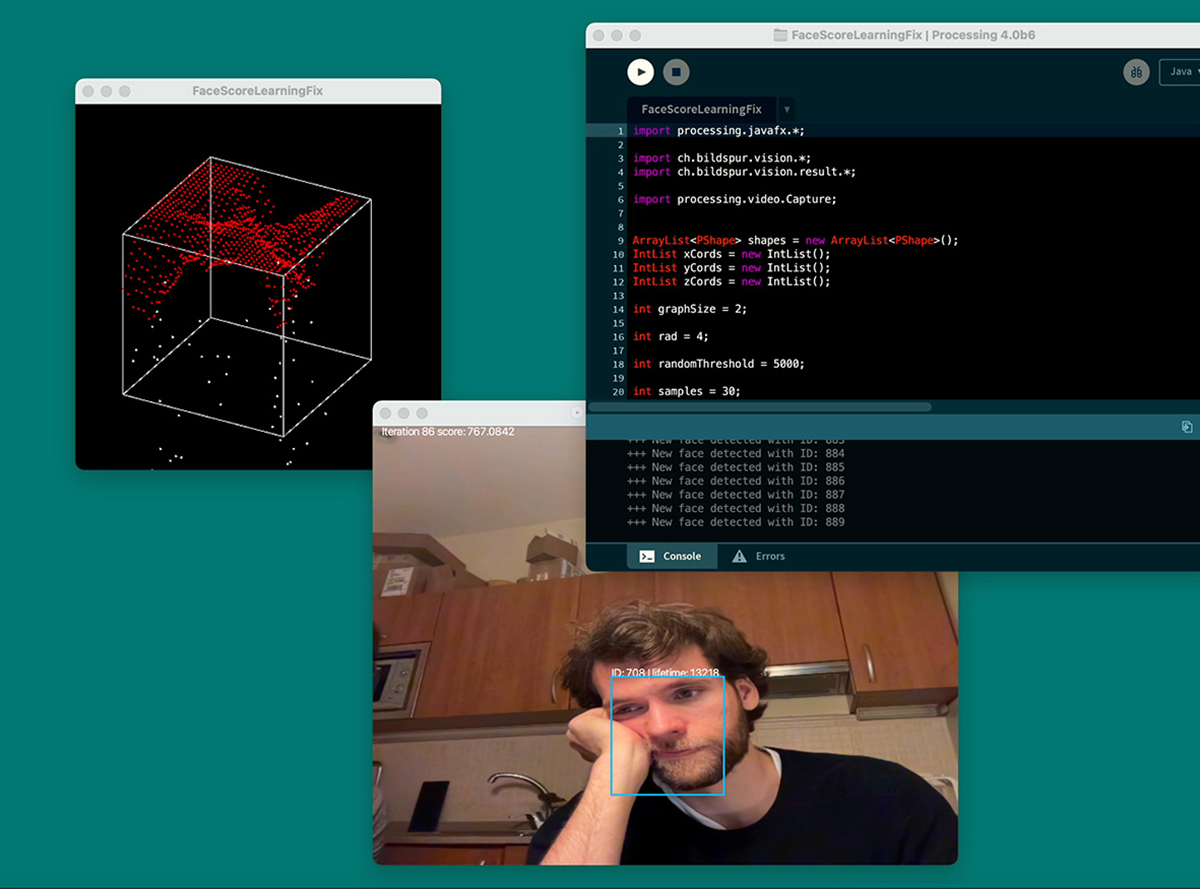

Although I have done some research on it, I finally came to the conclusion that this technology is not yet readily accessible, and would require too many concessions. Instead, a camera is used to recognise faces in the direct proximity of the artwork, and to measure the duration of their presence, working on the assumption that in an exhibition setting, standing in front of an artwork with your face turned towards it means you are observing it. This software solution was completed and tested, but it is not the one included in my diploma project, because the installation wouldn’t have had sufficient time and opportunity to learn from visitors at an exhibition lasting only a few days. In comparison, with the online video chat, it was possible to move on to the next participant at a push of a button, and during the 100-hour learning phase, the system received input from roughly 14,500 people.

You also stated that the key question raised here is how anthropomorphic the behaviour demonstrated by the installation was. Seeing the process and the outcome, what conclusion did you come to?

In retrospect, it wasn’t necessarily the key question here after all, although definitely an important one.During the induction phase, when the system spent 100 hours doing online video chats, there were many people who chose to talk to it, or mimic its movements in some way, like dancing with it.I feel that people interpreting the movements of a machine as dancing is outright anthropomorphisation. At the end of the day, what I’m trying to communicate and the context I placed the artwork into also matters a lot. Obviously it makes the question of how successful it was to present an anthropomorphic behaviour somewhat arbitrary, but I don’t mind this at all.

Then another question begs itself – what were the stakes for you in this project?

The artwork – if you still insist on calling it that – is the sum of all the gestures, processes, and decisions that I used to define the purpose of the installation, develop the logic of its behaviour, give it a body, complete the induction, display a ‘solution’, and analyse data from the learning also afterwards.

On the one hand, the project has a technical experiment aspect, on the other, there is the irony of having trained a makeshift machine to do useless things as if it were. Can your masterwork be seen as a distorting mirror of machine learning and the prompt hype?

Irony is useful for asking critical questions, but what I enjoy most about this type of design is playfulness, that you can do serious work on completely unserious things. I’m responding to the prompt hype with something more like defiance, deciding to stick with something so absurdly simple as my own machine learning logic in an age where all you can hear about are these mostly textual or visual, grandiose, generative models and making art using them. Of course I have more than one reason for doing this, and I could go on about them forever.

So the distorting mirror concept is just one of the many possible interpretations.

I am unable to describe what it’s all about in one simple sentence, but I have a lot of anxiety condensed into this work, and it is a distorting mirror of several things:

The naivety often demonstrated by both users and developers when it comes to machine learning and MI tools and their use – the ideal of the machine software behaving like a human. Systems built on a pathetic constant clamouring for attention are also loaded with associations, whether we to humans or to algorithms.

And ultimately the fact that this entity is attempting to optimise itself to become the ‘ideal artefact’, and that within its own conceptual framework this is achieved by garnering the most attention from visitors.

In an interview published in Jelenkor, you claimed to be a bad artist because you love working for the drawer. In this regard, what kind of future do you see for Beep-boop as an installation taught for 100 hours? Do you see a potential for moving forward with it, or will you withdraw it for good?

If I could give you an answer now, my statement quoted from the previous interview would no longer be true. What has definitely become clear also from this conversation is that there are plenty of loose threads and alternative aspects not explored. The theoretical possibilities for moving forward are there, and we’ll see how the rest will turn out.

// /

The masterwork was completed at the Media Design MA of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, with László Halák and Cseh Dániel as consultants and József Tasnádi as supervisor.