“Reuse is a harder but more meaningful way”

There are few more haunting spectres in a city than the skeletons of buildings left to decay, which is exactly the sort of sight the dilapidated sets of the Communist regime scattered all over offer. Not yet demolished, and either used for their original or a new purpose but most often left vacant, these buildings all share a deep silence around their past. As mausoleums of Socialism, their ominous silence suggests that time may have passed but the ghost is still haunting. However, the latest generation of young professionals is less scared of old ghosts and more fearless when it comes to shining a light into the obscurity of memories surrounding the buildings to recover what is worthy of being preserved. Lilla Gollob’s masterwork research, for which she received the Rector’s Award, represents a similar attempt. Interview.

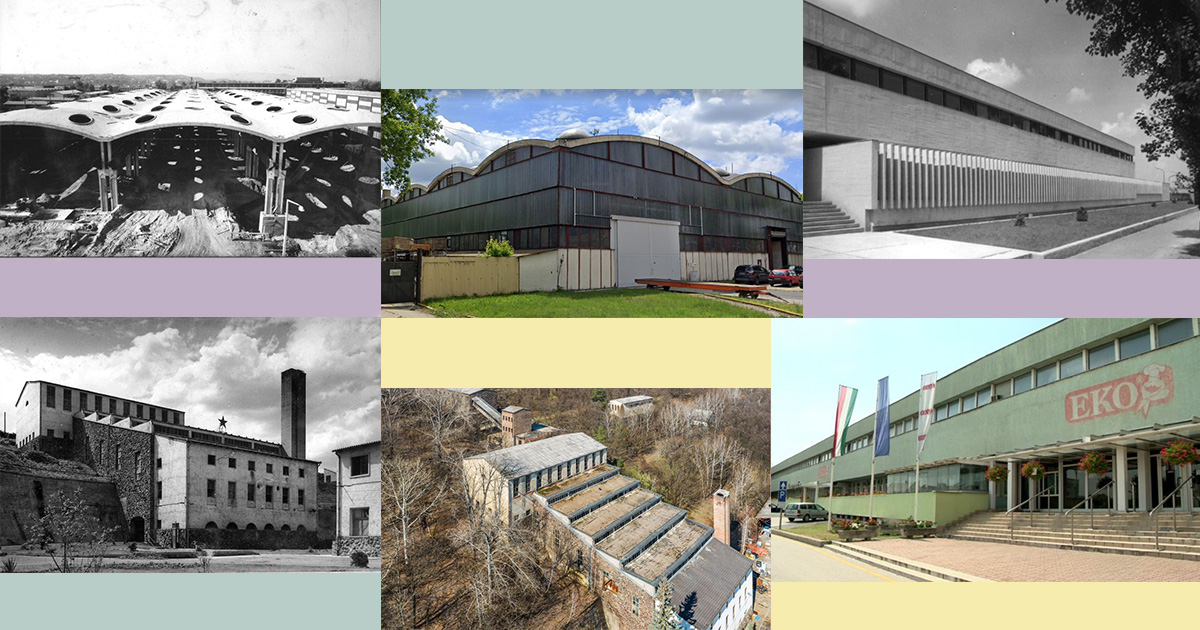

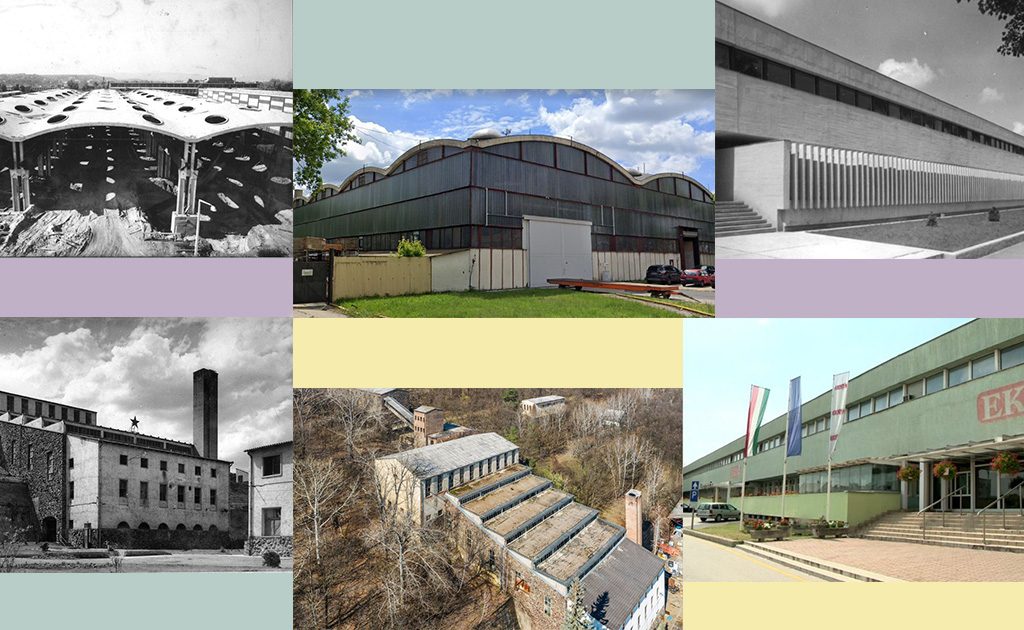

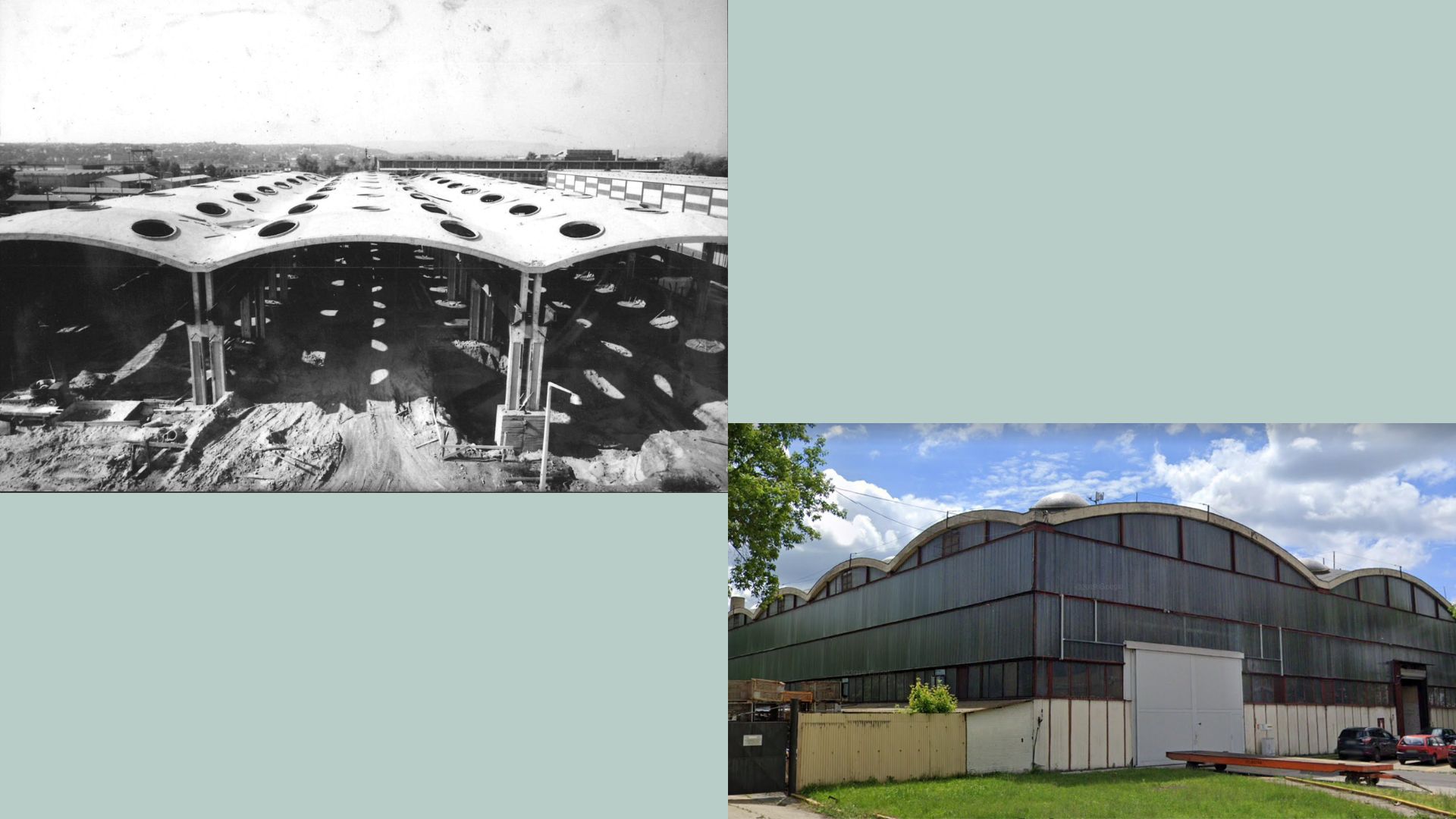

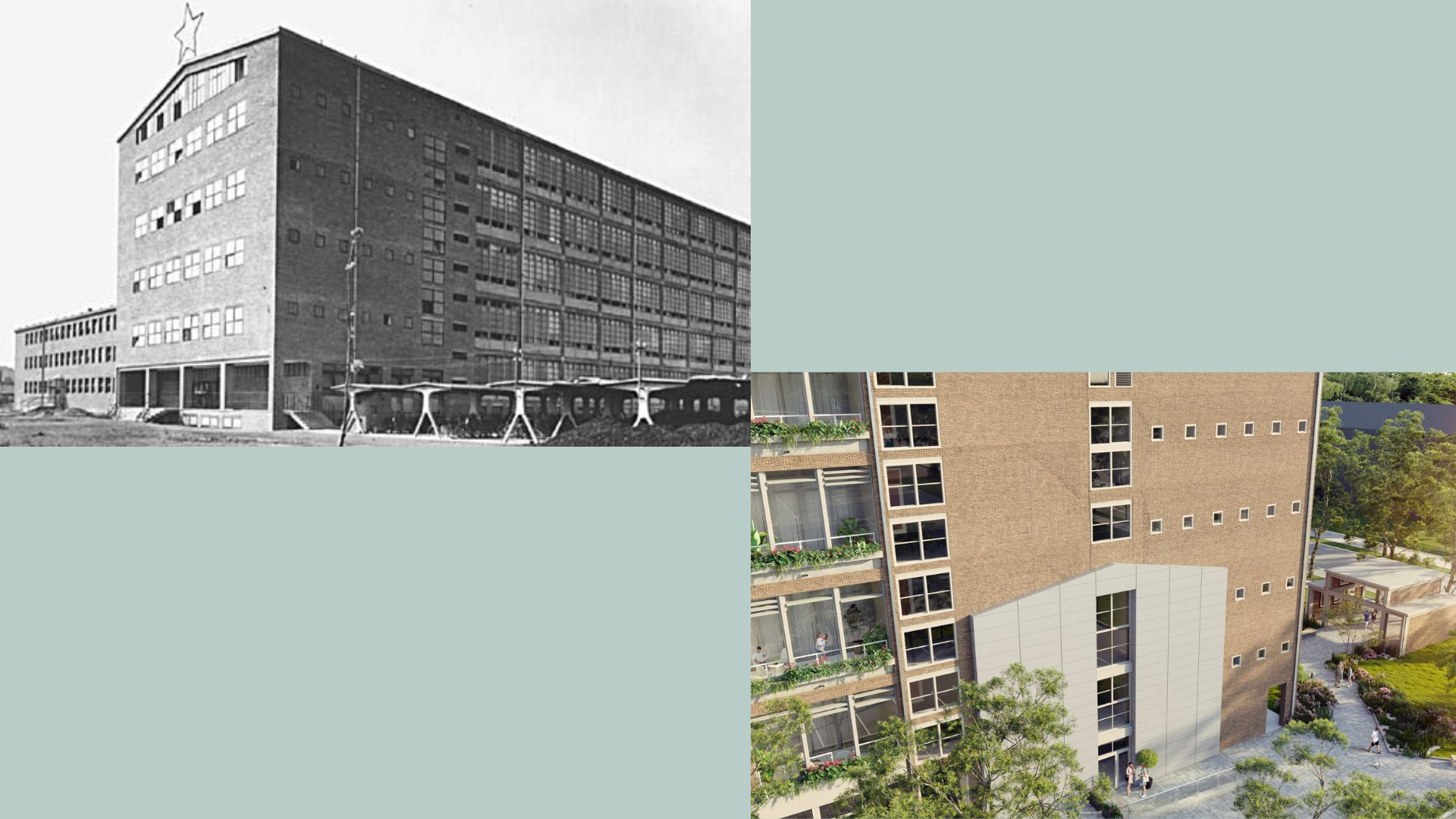

Iron and metal factory at Csepel then and now

Your research explored the current state of the architectural legacy left by the Industrial Architecture Design Company (Hungarian abbreviation: IPARTERV), in particular value preserving reuse. In one of your articles you wrote “Value preserving reuse should be the most important focus of contemporary architecture”. What exactly do you mean by that and what could be the explanation for the slow shift in mindset?

The concept of contemporary is often linked to chasing the latest and most modern things. In architecture, it normally refers to the spectacular, high-tech buildings designed by star architects. At the same time, in 2023, in the middle of the climate crisis, it is becoming all the more pressing to consider alternatives to demolitions and rebuilding – both of which come with an enormous carbon footprint – when it comes to existing buildings that have lost their original function. How could they be placed in a contemporary context and reintegrated into the urban fabric while preserving their architectural values? In her graduation speech at the MOME MA graduation ceremony, Zsófia Csomay used the term ‘quiet architecture’, a philosophy that focuses on value preservation and creation without resorting to flamboyant solutions. Reuse projects, in particular abandoned industrial complexes, could be focus points of quiet architecture. This slow shift in perspective is also linked to established economic considerations, as the optimal conversion of old buildings require more thought and represents a more complex challenge than demolition and building anew. Reuse is a harder but more meaningful way in many respects.

You also highlighted that even though the industrial building stock could be reused exceptionally well, in our region the buildings are haunted by memories of the Soviet era. Is this a specifically Central Eastern European dilemma?

Though the reuse of abandoned buildings and factory buildings is a global dilemma, there is a strong local Central Eastern European bias. In the second half of the 20th century, many industrial complexes with high architectural value were built to modern international architectural standards. However, after the change of regime, many of them were abandoned and has become saddled with negative associations. Since then, what we see – and what the research for my thesis confirms – is that they are contextualised and reused in a negligible number of cases only. Most of the time they are either demolished or left to decay. In those rare cases where industrial production is still ongoing, they are affected by a strong decline in aesthetic quality. The once elegant, unconventional structures become mediocre-looking or downright hideous after being given a sloppy cladding, as perfectly illustrated by the before-after photos of the Nyíregyháza Canning Factory.

Metal factory at Gyöngyösoroszi now and then

It is a sad fate for an essentially valuable legacy…

In the eyes of the public and government decision-makers, the buildings themselves do not represent any value or are downright universally loathed given their historical baggage. In Hungary, brand new building projects like the MOL Tower and the Liget Project or reconstructions of buildings from earlier periods would happen sooner than dealing with this part of our shared heritage. The majority of well-known examples are from Western Europe – just think Tate Modern in London or the NDSM in Amsterdam. Recently I was passing through Romania and in a matter of a few hours I saw an immense number of abandoned industrial buildings. We can safely say that in Central Eastern Europe, supply currently outstrips demand. And if someone decides to deal with industrial buildings for once, they are normally brick structures from before the 20th century, such as Millenáris Park or Csepel Works, where the modern buildings were either demolished or left unrenovated.

With your supervisor Péter Haba you have put together a mind-blowingly large catalogue with 113 building reconstructions. What criteria did you use for the selection of your building stock?

Although there is much said about demolitions and abandoned, run-down industrial buildings, there are no lists or registers of the afterlife of modern Hungarian industrial buildings. To remedy this, Péter Haba, the most eminent expert of the subject in Hungary, and I started a review of the Hungarian situation. Without his help, the research could not have been done this smoothly. The Industrial Architecture Design Company (Hungarian abbreviation: IPARTERV), the most important architectural player of Socialist industrialisation, was identified as the focus of our review. In addition to its privileged state, a lucky confluence of circumstances gave rise to a vibrant professional environment within the company. Our goal was to assess the current condition of the facilities built in the most productive period of the company – between 1948 and 1970 – by creating a not-too-large yet representative database. The selection was made by merging and narrowing down four building registries from that period. These publications were all linked to IPARTERV in some way, either because they were published by IPARTERV or edited by Jenő Szendrői from IPARTERV. Our database is based on the jubilee IPARTERV register of 1974, from which we developed our own selection, narrowing it down to exclude buildings designed by IPARTERV after the designated period or for export, as well as lying outside the scope of the research, such as residential buildings and hotels. Next, this list was compared against and updated to include buildings from three other previous catalogues*. This listed building stock represents a first step and can be further expanded later on.

Power plant at Inota then and now

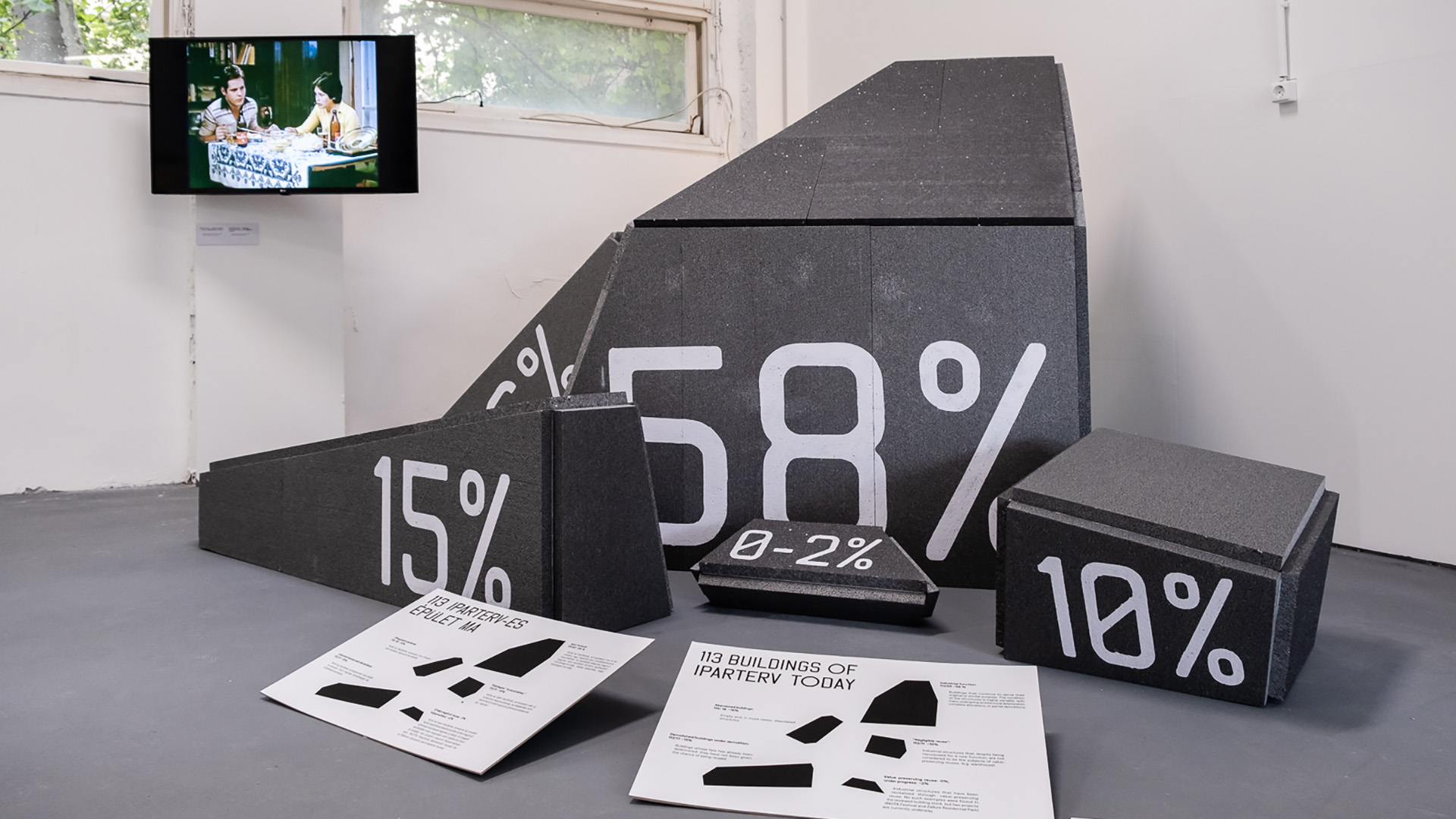

Based on their current state and functions, you have classified the buildings into five categories. More than half of them (58%) were put in the industrial function category, a large number were demolished (15%) or left to fall in disrepair (16%). Some (10%) were identified as having a potential change of function, and only two projects (2%) were characterised as undergoing value preserving reuse. What were your criteria for distinguishing between a “potential” change of function and true value preserving reuse?

The aim of creating categories was to gain a better understanding of the use rates, and so making a clear distinction between them and giving them a name was a huge challenge. Potential function change was defined as the new function not meeting the requirement for the building to qualify as a good example, i.e. while the building escaped demolition or complete decay, it didn’t enjoy a happy afterlife. Examples include the Power Tool Production Hall of the Csepel Iron and Metal Works, which survived in a relatively good condition, and is used as a warehouse today, and the Ganz-Mávag Diesel Engine Factory in Kőbánya, which is in a much more dilapidated and filthy state, and currently housing a Chinese market. Value preserving renovation involves taking a more complex and creative approach to the buildings. Strictly speaking, 0% of the reviewed database underwent value preserving reuse, an important and rather telling finding. I included two cases here, though, that are currently undergoing revitalisation, keeping in line with the architectural history and industrial aesthetics of the buildings. One is the conversion of the Zalaegerszeg Clothing Factory into loft apartment complexes and the other one is the organisation of the INOTA Festival on the premises of the former Inota Heat Plant directed at long-term utilisation and rehabilitation of the complex. There are also borderline cases, for instance the former Cable Factory that was converted into the Újbuda Center. For this reason, I made a point of underlining in my thesis several times that making a distinction between various reuse practices is indicative.

The work of MINISPLUS architecture studio

Your research presents successful Hungarian and international value preserving reuse practices, such as the office space created by the MINISPLUS Architect Office inside the former South Buda Ventilation Machine Factory, or Fabrika Tbilisi, a multifunctional cluster converted from an old Soviet Clothing Factory. What could be behind the success of these two focus projects?

The key to the enormous success of the two projects was the ability to revitalise the buildings while retaining their original character. In the MINISPLUS project, the building was already owned by the client, who contacted the architect office to design the conversion. The speciality of the conversion is that the new glass building occupying two thirds of the hall met modern requirements and the expectation for architectural value preservation. The offices located in the glass ‘box’ thus fully meet today’s energy requirements and expectations regarding office comfort, and overlook the fascinating original structure of the building. In the case of Fabrika, it was MUA, a local architect office, that came up with the idea of purchasing and reinventing the abandoned Socialist clothing factory of Tbilisi. A cost-efficient reuse programme was developed to expand the culture hub function of the building while ensuring it was economically sustainable. For this purpose, in addition to studios, exhibition spaces, and design stores, a hostel, a café, a co-working space, and teaching spaces were also added, invigorating not only the building but the entire neighbourhood.

You conducted your architecture-focused research at the Art and Design Management MA programme and so your thesis also included a focus on management knowledge. What (architectural) management prospects can you see for yourself in this regard? What role do you see for yourself in the value preserving reuse of industrial buildings?

Architectural managers often act as a bridge between architects, lay people, investors, contractors, city governments, and other roles. I’m currently working as a journalist and editor for Octogon magazine, which means I’m mostly seeking to forge a bridge between the professional community and our readership by improving the visibility of industrial reuse projects and highlighting the relevance and potential of the subject. For now, the most important means for this are the INDUST-REUSE article series launched by me that identifies and presents examples of industrial reuse, as well as the media partnership between the magazine and the Inota Festival. Completing the MOME Design Theory BA programme before proceeding to the Art and Design Management MA programme had a tremendous influence on my theoretically oriented professional identity. In the future, I would love to take on more specific managerial responsibilities in industrial reuse projects, supporting liaising between architects, investors, and prospective users.

In addition to local, ongoing value preserving reuse projects, the Unknown IPARTERV – The Halcion Days of a Design Company 1948–1970, a recent exhibition featuring a part of your research, was on display at the Rózsi Walter villa. In a way, it can be seen as an attempt to rehabilitate the company as well as the industrial building stock of the Socialist era. What do you think is the explanation for the increased interest in this subject both within the professional community and beyond?

I think there could be more than one explanation, but perhaps most importantly, the generation that was born after the change of regime is coming of age now, also in the professional sense. The industrial buildings designed by Hungarian architects combine all the colour and spice of the 20th century, giving this medley of monumental structures, iron and steel structures, functionalism, modernism, and pinch of Social Realism an especially powerful and individual aesthetics. We are able to take a step back and look at this period from a distance, and see the value and the cool factor in these buildings, while also being able to easily relate to the sustainable aspect of reuse practices. That being said, the important groundwork has been laid by a narrow professional circle dedicated to preserving the built legacy of the period with their past and continued contribution. The approach and work of university teachers at MOME such as Péter Haba, Zsófia Csomay, András Ferkai or Gergely Hartmann greatly help students today in developing an understanding of and a fondness for this architectural legacy. Being the optimist I am, I hope that each university course, article, book, exhibition, and successful reuse practice can contribute to preventing our modern industrial architectural heritage from vanishing without a trace.

// /

* Hungarian architecture 1945–1955, Our industrial architecture, Hungarian architecture 1945-70

Lilla Gollob’s diploma research The IPARTERV and beyond – The state and reuse options of our post-World War 2 industrial architectural legacy was completed at the MOME Art and Design Management MA programme, with Péter Haba as her supervisor.