Between conflicting narratives – Confrontation by Judit Spanyár

Following the 20th century riddled with social crises, most Hungarian families probably have stories that have the power to turn the atmosphere chilly when they come up at social gatherings – if they are brought up at all. In these times of pluralistic history, the collective historiography of a nation is just one of the many narratives that could drastically differ from various private recollections.[1] But what happens if the conflicting experiences occur within the same family? Judit Spanyár’s photo project Confrontation explores the conflict between the opposing individual stories.

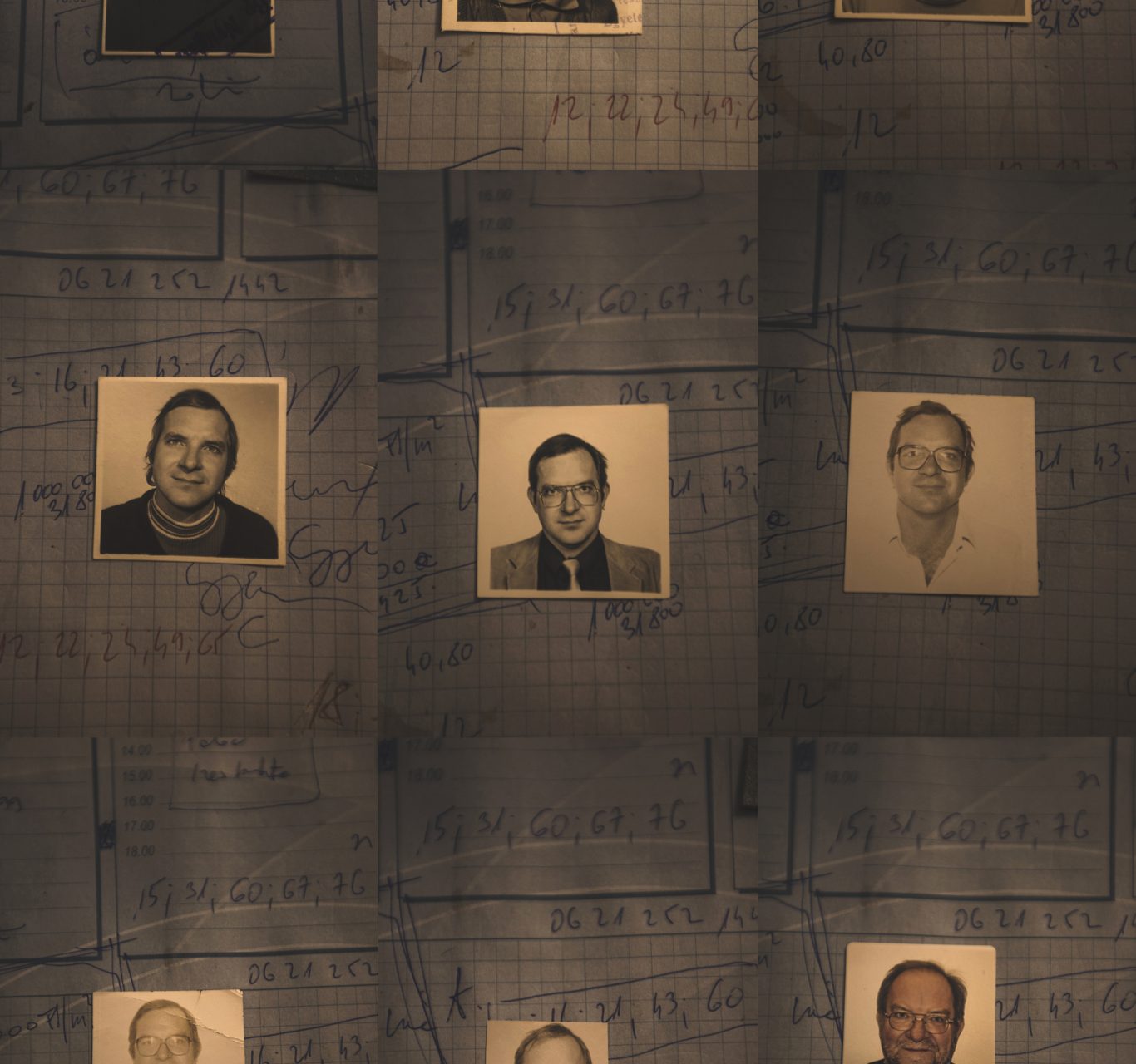

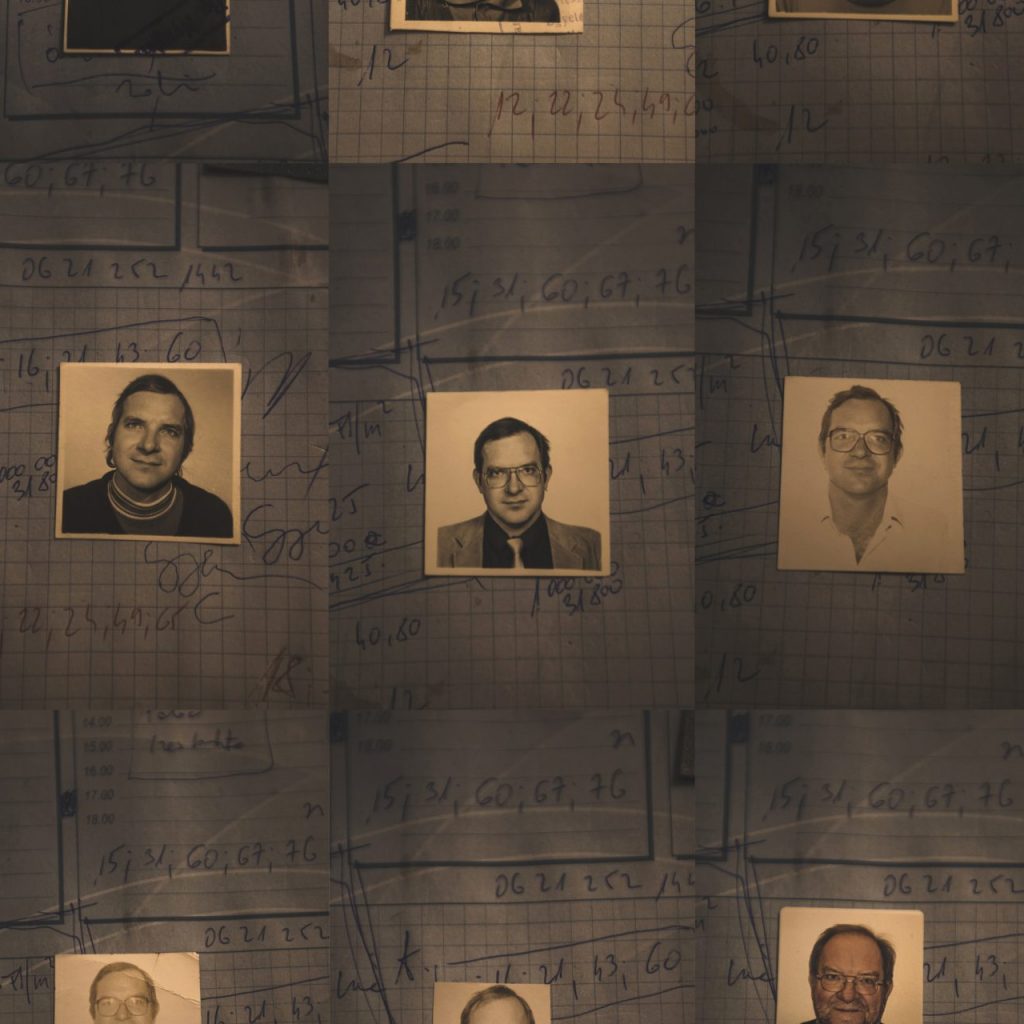

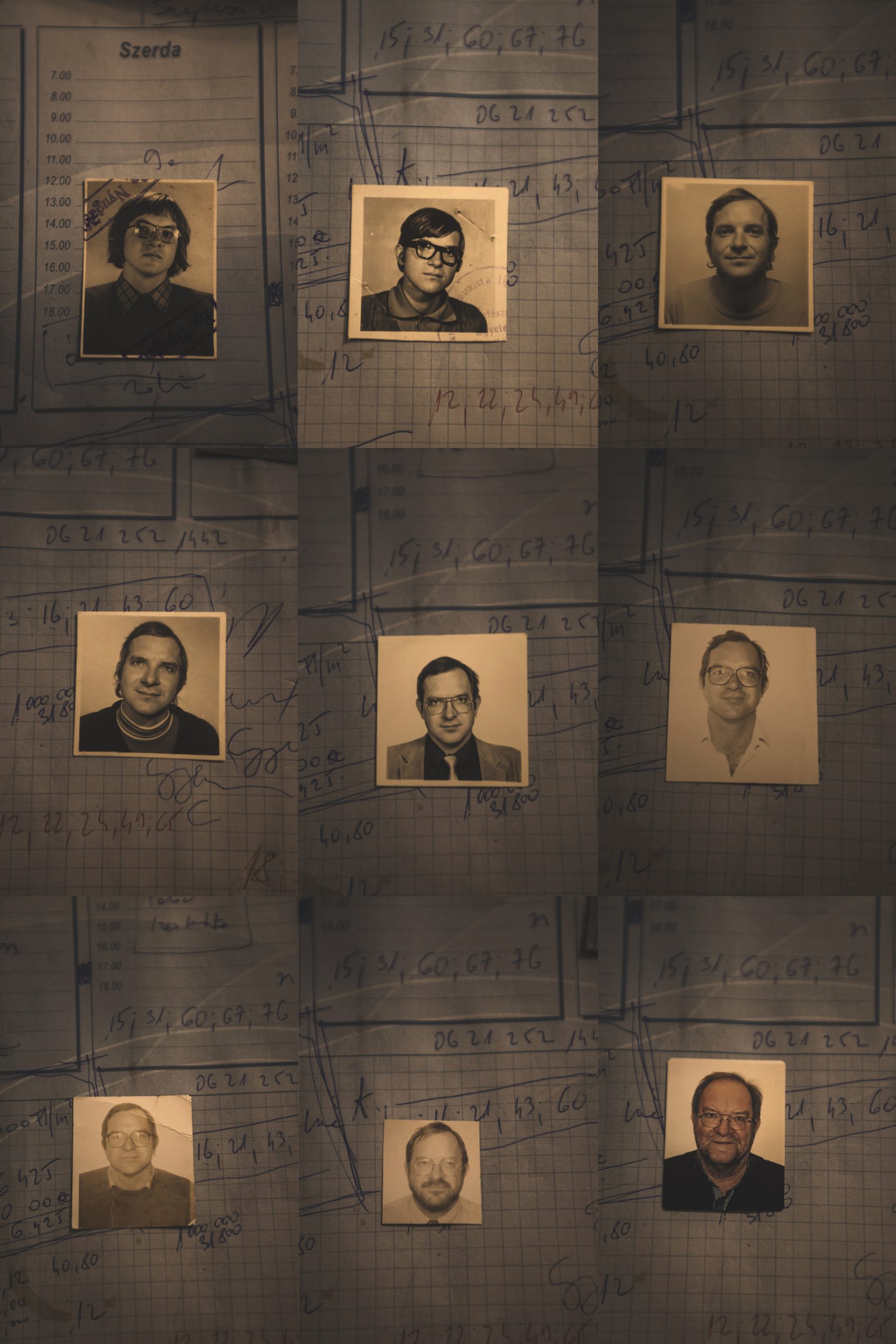

“During the era of nationalisation, my grandfather, who was serving as a court judge in the late 1940s, also played a part in the seizure of the mansion and estates of my husband’s family belonging to the landed gentry His signature was also found on one of the documents giving my husband’s great-grandfather a prison sentence for hiding a crate of ammunition.”

Perhaps nothing can put the unity of a family more to the test than the emergence of a story like Judit’s. The descendants are put in a difficult position, as the seemingly unprovoked eruption of emotions can be traced back to unresolved traumas that cannot be properly pieced together from the incomplete archives. As lieux di mémoire, or places of recollections, the scenes of the documents, items, or even stories left behind can play a crucial role in our search for identity. It is no coincidence the study of the archives has been part of research-based art projects since decades. As Flóra Gadó underlined in a paper, the personal involvement can manifest through performative gestures in the works of contemporary artists, not only processing but also “activating” the archives.

Chapters of Confrontation are linked by performances partly related to family legacy, partly interpreted metaphorically. The posed photos taken during their visit to the remains of the confiscated estate in Alsóörspuszta feature Judit’s children, her husband and her father. The scene of the conflict-laden memories are transformed into a stage as the different generations are searching for how to relate to the present situation among the ruins. One of the photos depicts Judit’s younger daughter, with a family heirloom slipping out of her hands. This re-enactment of Ai Weiwei’s famous performance might prompt us to reflect on the valuable albeit burdensome nature of the exploration of the past.

Dropping a China jug is a radical, agitated interference with memory. In contrast, Judit’s approach to the photo of her grandfather involves a milder gesture. The physical similarity between the two of them is reinforced by the act of dressing up in the same clothes, which can at the same time be construed as an attempt to emphatically relate to a person only known from family anecdotes. What we see is the line separating the past and present, and heavy issues wherever we look. “I wanted to understand him. It took me time to realise that anyone can become the victim or the offender – there is no person without faults, and the only difference lies in the gravity of our faults. We cannot always figure out the motives of our ancestors or deny their offences, but we can also decide not to take them upon ourselves.”

The motif of undressing and getting dressed recurs in the joint performance of the family members, which, taking a step back from the reactivation of the legacy, takes on a more metaphoric register. The persons subtly highlighted against a black background with soft diffuse light bow under their shared burden, linked by the motif of wearing the same white shirt. While the family members keep their faces turned away from the camera, Judit’s determined gaze embracing her vulnerability meets the viewer’s, perhaps signalling that despite the involvement of her entire family, it is mostly she who took on the burden of confrontation.

“I am so preoccupied with this issue because I want my children to clearly see the processes, emotions, and reactions produced by the antagonism resulting from different interpretations of the historical past. In my experience, they are struggling to process historical memories when they create tension in the present, when the argument over different views of past events creates heat. Confronting the events of the past, our own feelings, preconceptions, and guilt, no matter how difficult, is essential for making sense of them and being open to each other.”

// /

[1] Nora, Pierre: Between Memory and History, 1984

Judit Spanyár’s diploma work Confrontation was created at the Photography MA programme of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design with Gábor Arion Kudász as her supervisor.