The construction of an artist – Interview with Elina Brotherus

There is a pleasant strangeness to seeing her in real life, after so many years of only looking at her self-portraits. I’ve became accustomed to seeing her likeness in carefully chosen and constructed photographic settings, with her gaze at times raw and quietly piercing, other times distant or turned away from the camera. Over the past two decades, Elina Brotherus has become one of the most famous Scandinavian artists. Her rich body of work is recognizable not only by her regularly reappearing, familiar figure, but also the characteristic aesthetic language used and the questionsposed. On the occasion of her visit and artist talk at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design Budapest, we had the opportunity to ask her about her artistic approach in more depth.

You’ve been invited to MOME for the Course Week as a guest-lecturer. In your artist talk, you mentioned that you only teach a couple of classes every year. What’s it like for you to mentor young artists?

It’s like putting my finger on the pulse of time in order to see what young people are thinking, doing, and what kind of aesthetic language they are using. I was a student in the 1990s myself and most of my friends and colleagues are from that generation. Teaching is a way for me to find out what’s going on in the new, up-and-coming artist-generation.

Does their work affect yours?

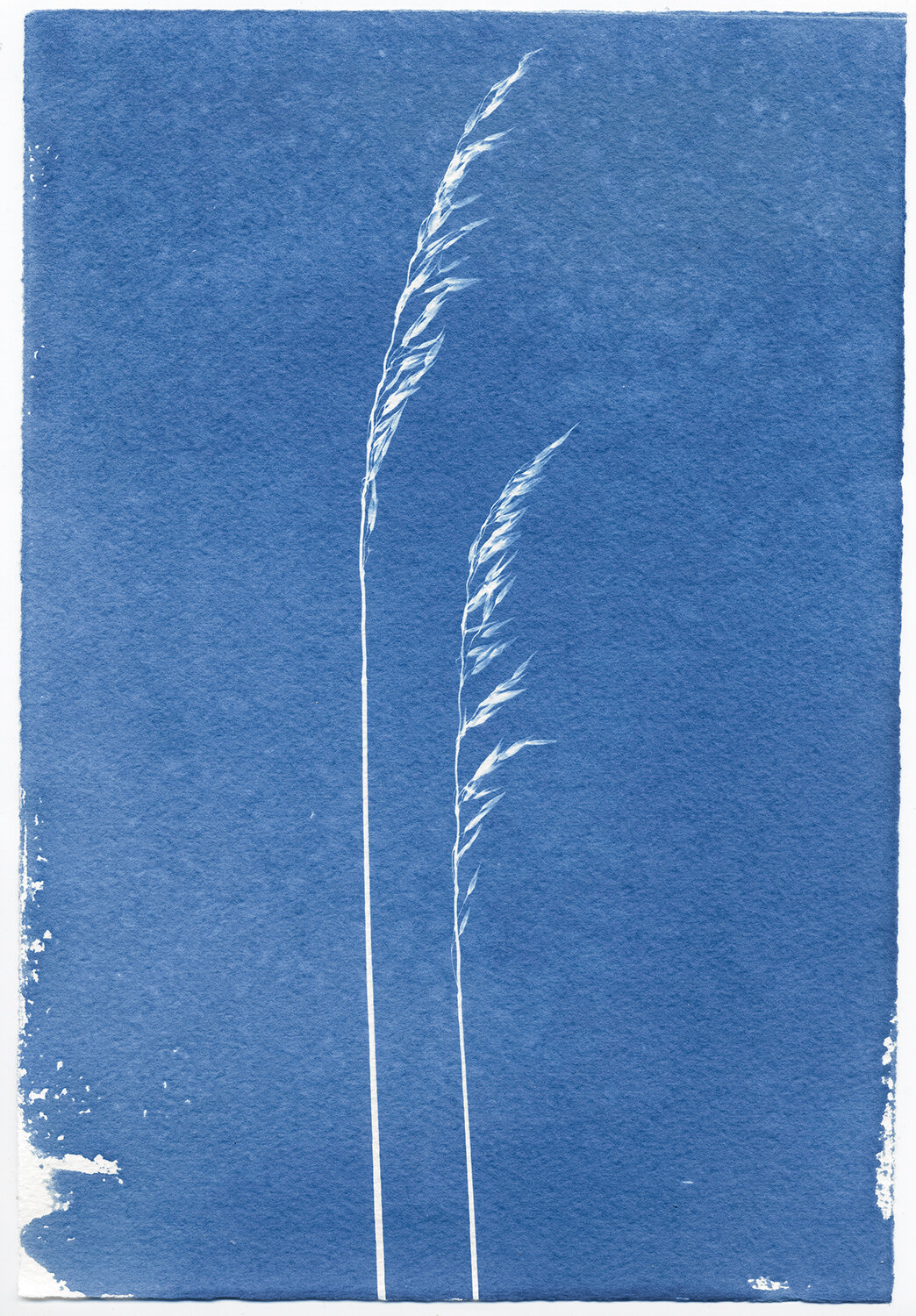

Let’s just say that they often give me the desire to try something that I might not normally do; to change up my practice to be more experimental. For a long time, I’ve been wanting to do something more manual like collage, or to use some other medium than a framed print on the wall. I’ve been taking baby steps towards broadening my practice – for instance, I did cyanotypes, installations that included a huge wallpaper, and I also displayed some objects and books. I admire the freedom young people have in employing different mediums and materials in their photo-based thinking.

Science Class 2. 2014, 60×90 cm from the series Carpe Fucking Diem (2011-2015)

Before dedicating yourself to photography, you had started your academic studies in the field of science, more specifically, chemistry. Does this early connection to the scientific approach affect your work?

I think it shaped who I am today, but it doesn’t necessarily inform my artistic practice. I don’t do anything science-related in my photography, but the way I think, the rigor I have when needed probably comes from the time I had to sit down and read hundreds of pages of complicated things.

While browsing through your portfolio, I chanced upon two self-portraits in your series titled Carpe Fucking Diem, that were taken in a science lab. These made me wonder about possible connections.

That was actually a chance encounter with the lab but it’s a very good example of how I work; I let things happen and when I see something interesting, I capture it. When taking the two pictures you’ve mentioned, Science Class 1 and 2, I was actually teaching a workshop at Les Rencontres d’Arles. I led these workshops for several years and the concept was that the organisers took me and my students to an unknown place where we were supposed to produce some work – all of us, including me. The students were working on their own thing, but they could also see me at work. In 2014, we were taken to an abandoned primary school building that still had these science classrooms.

On the left, Tombeau imaginaire 26 (édition), 2019, 32×32 cm (edition 25+5AP) from the series Sebaldiana. Memento Mori (2019) // On the right, Couple in the mountains, 2007, 80×99 cm from the series Artist and her Model, (2005-2011)

Your artistic practice includes a lot of travelling – in your words, you lead a ‘wanderer-lifestyle’. I sense an interesting contradiction between your freestyle approach and the carefully constructed nature of your photographs.

There are so many ways to construct a body of work or make yourself come alive as an artist. I admire people who stay in one place for their whole lives or analyze one subject matter throughout their career. Even if you photograph in your home country for your whole life, it appears different every day, so you can start seeing variations on the same theme. I think I’m a little bit impatient for this – that’s probably one of the reasons why I changed from science to art. I just couldn’t bear the fact that the results of my work would stay somewhere below the horizon for years – I want to get the results now. Even when I was a student and shot on film, I would drop the negative off at a laboratory so I could get the photos back by morning. This is the kind of time span I am happier with.

And about travelling, I need to soak up new scenery every once in a while, because if I saw the same streets every day, I would stop seeing altogether.

The workshops I do a few times a year are perfect opportunities for that. Unfortunately, I don’t have much time to take photos here in Budapest, because I have a big group and I work long hours every day. But on the first day, I went for a walk in the woods on the hill behind the university’s buildings, and I took one picture.

My mother’s wedding dress, my father’s wedding suit, my mother’s funeral dress, 1997, 150×110 cm // exhibition view and portrait of the artist at Galeria Anhava, 1998

Some of your work is deeply autobiographical. Looking at the self-portraits of My mother’s wedding dress, my father’s wedding suit, my mother’s funeral dress or Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe I get the sense that you are diving into your emotions while simultaneously – by taking photographs – you are creating distance from them. It sounds emotionally burdensome.

Well, you mentioned my science background; maybe that’s what comes through in these early autobiographical works. I had completed my science studies around the same time, so the experience was still quite fresh for me.

I feel as if I was observing my emotions from the outside; kind of like being the scientist and the specimen at the same time.

Photography, of course, made this possible by giving me a neutral way to look at myself; especially because I shot analogue, so I couldn’t see the results immediately. This enabled me to stay connected with my emotions and just focus on taking pictures. My motto at the time was that ‘it has to be genuine’, so I only took photos when something was happening at that very moment; I would never stage anything afterwards. I always had my camera on a tripod in my room so when something was happening, I could immediately react by taking pictures. This approach helped me getting used to the camera, so that it felt like a good presence and not something violating my privacy. Also, it was me taking photos of myself and not somebody else, so I was always in control of what I wanted to show to the spectators. I’ve never censored myself at the moment of picture-taking, but I do edit the photos later.

You’re continuously switching between autobiographical and arthistory-based approach. How do these switches happen? What triggers them?

Art follows life, so I do autobiographical work when I feel the need to do it. At some point, it exhausts itself, so I swerve into another direction. I work on several series in parallel, such as my long-term projects on “instruction art” or modern architecture. This year I’m working for Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg that combines the two: It’s a building designed by Alvar Aalto and they have a great Fluxus collection. I’m going to work in its interior to create a dialogue with their collection. Having more projects going on at the same time helps not feel like I rely only on just one idea, because if I was stuck with that, I would be stuck completely.

Imaginary Burial Place 18, 2019, 120×90 cm, Herbarium Pianense 41, 2019, 28,0×19,0 cm (cyanotype photogram) and Sebald’s Hotel 2, 2019, 80×106 cm from the series Sebaldiana. Memento Mori (2019)

What continues to fascinate me in your approach is the light-hearted fun that radiates from some of your series. Having been in the art world for more than 20 years, how do you manage when your plans don’t work out, or when you feel truly stuck?

I don’t think it’s necessary to produce pictures all the time. It’s only natural that you have times of production and then times when you do exhibitions for instance. Exhibition-making is of course very much related to art. There are artists for whom the exhibition is the format they use to create something new, but my exhibitions consist mainly of pre–existing pieces. Then, there’s this other side to the life of an artist that nobody really talks about or doesn’t even know about when they’re young: the huge amount of personal administration. It’s the emailing, planning, correspondence, and logistics that eats up about 70% of my time. If you think about it, that doesn’t leave that much time for actual artmaking. That is the reason why, in recent years, I have been creating art in concise periods. For instance, I was invited to Corsica a couple years ago by a photography art centre. I had the idea to follow W. G. Sebald, who was writing a book about Corsica, but then he died, so the book was left unfinished. Some excerpts have been published posthumously, so I took them as my ‘guidebook’ to Corsica. I followed him to the places he describes in the book and created a dialogue with him. Such short-term, intensive work suits me really well, because it allows me to not pay attention to the chaos of everyday life and just look for pictures.

Sounds like the perfect dream for an artist!

Yes, that’s why I encourage young students to apply for foreign artist residencies. This is how you build a network; you can meet other artists, curators, and get your work out there. It’s really important to get out and travel because it’s hard to make a living as an artist if you stay in a small country like Hungary or Finland. I would not be able to support myself if I only worked in Finland because it is a peripheral and very inward-looking country. The world is one big place today, everybody speaks English, and the open calls are open for everybody. So, I encourage people to constantly research what options there are. Also, young artists should start sending out their works while they are still studying. At school, they have all the facilities to print photos or produce book dummies for a cheaper price, and they can still get feedback from their teachers. If they manage to get started while they are still at school, the transition is a lot easier to make.

One Minute Sculpture with Erwin Wurm (Carry and Levitate), 2018, 120 x 90 cm, After Erwin Wurm, Carry and Levitate, 2008 from the series One Minute Sculptures (2017-) // In the Sky Unlike a Bird, 2017, 90 x 67 cm After Tuomas Timonen, You are in the sky unlike / a bird in the sky, 2015 from the series Règle du Jeu (2016-2017) // Artist as Clown, 2020, 90 x 120 cm from the series Meaningless Work (2016-)

You have already mentioned your instruction art project, in which you reinterpret Fluxus event scores. What do you think Fluxus art can say in the present time?

I think Fluxus artists had a wonderful freedom of thought and a joy of living that really speaks to me today. I believe art is universal and timeless; the problem is that looking at the cracks on a painting or a low-resolution video image makes us consider artworks old. But if we look past materiality and into what the works are about, we can see their relevance today as well. The questions artists raised in the ‘60s are still very topical.

It’s good to look back and see what others were doing before, so that we don’t falsely believe we invented something new. We are a part of a discussion that has been going on for decades, even centuries, so it’s important to acknowledge the people who have come before us, see them as our allies, learn from and have fun with their work.

I feel like the Fluxus project is an art school of my own invention where I have selected teachers to collaborate with. That’s why I always want to mention the artists whose event score I use.

On the left, Le Nez de Monsieur Cheval, 1999, 80×102 cm from the series Suites françaises, (1999) // On the right, La Chambre 10 (la porte jaune), 2012, 80×100 cm from the series 12 ans après, (2011-2013)

You are not only reinterpreting other artists’ works, but also your own previous ones. For instance, you created a sequel called 12 ans après to Suites françaises, and your Black Bay Sequence video was also based on an earlier video called Baigneurs. I’m curious as to what it is like, what does it mean for you as an artist to revisit an earlier work?

I think I’m still interested in the same things I was concerned with as a young artist. As if there were these big questions that still feel adequate for me to ask again and again. Photographers are essentially observers and collectors – we like looking at things, comparing, and collecting them. Also, the photograph is like a time machine; you can travel back and do the same thing again. I’m using my own body, so it’s really interesting to see the changes of the same human figure. Think of Roman Opalka’s self-portraits! That’s one of my absolute favorite artworks in the whole world – and it’s just the passport-framing of the same face turning from a young person into a white-haired old man who eventually dies. It’s such an existentially heartbreaking work.

In recent years, you’ve embarked on a new artistic chapter with the use of modern buildings as the setting for your self-portraits. In the series, we can see iconic places, such as the Aalto House, coming alive. What made you interested in modern architecture?

It was also one of those chance encounters. There is a building on the outskirts of Paris called Maison Louis Carré, which is the only private house Alvar Aalto built outside of Finland – I would say it’s one of his masterpieces. When the widow of Louis Carré passed away, a foundation was created in order to turn the house into a museum. The director is an acquaintance of mine, and she told me, she wanted to start exhibiting contemporary art in the space. After all, Aalto had designed the house as a display for an art collection, since Louis Carré was a gallerist and a collector. After Carré’s death, the collection was auctioned off and the house was left empty. When the director invited me to exhibit something, I came up with the idea to take a picture in the house and showcase it as a kind of miseen abyme. I stayed there for three days, and this very well-designed space got me so inspired! I had never thought of architecture as something I would be interested in; I take two-dimensional pictures and I don’t easily comprehend how 3D objects like sculpture or spaces work. I got so carried away I was working like a maniac, following the light from room to room throughout the day, and ended up creating a whole series instead of just one picture. I realized that I actually enjoy doing this kind of photography and the results were also pretty interesting.

Office Stairs, 2020, 90×67 cm and Photo Boxes, 2020, 90×67 cm from the series In the Architect’s House (2020) // Piscine (Transat), 2018, 90×120 cm / AP 120 x 160 cm from the series Les Femmes De La Maison Carré (2015-2018)

They are really different from the architectural photography we usually see.

A Japanese professor, who is a specialist in Aalto, saw my work and said that he had never seen Aalto’s architecture presented this way. Although Aalto designed for the human experience and so the human scale was really important for him, we always see his buildings depicted as empty. Architecture needs the human presence for the spectator to understand the scale and to be invited into the space. In my architectural work I always look for private homes; public spaces don’t interest me. This allows me to play the inhabitants, their guests, visitors, or some anonymous women who could have been present in the house at some point in its history. So, I continue working on this series; I photographed in other Aalto-buildings that I got access to through the Alvar Aalto Foundation, and I visited other iconic houses as well. I would love to do the same in Hungary, too!

Model Study 8, 2004, 105×75 cm and Model Study 15, 2004, 80×63 cm from the series Model Studies (2002-2008)

Artists at Work 4 70×86 cm from the series Artists at Work (2009)

Morgen i Ny-Hellesund, 2018, 90x120cm and Aften i Ny-Hellesund, 2018, 90x120cm, After Amaldus Nielsen, Morgen i Ny-Hellesund, 1881, Sørlandets Kunstmuseum, Kristiansand, 42cm(h) x 65,5cm(w) x 3,5cm(d) from the series Seabound (2018-2019)

Artist as Mirror, 2019, 90×120 cm. After M.H.Abrams in The Mirror and the Lamp (1953) : “The change from imitation to expression, and from the mirror to the fountain, the lamp, and related analogies (- – -)” from the series Meaningless Work (2016-)

// /

Portrait is from the artist.

The photos are from the artist’s website.