“The fashion industry needs to pull itself up by its bootstraps” – Interview with Anna Keszeg

Anna Keszeg is one of the few theoreticians working towards creating a contemporary Hungarian fashion science discourse. Discussing her book published a few years ago in on the subject, a competition for fashion students, an initiative supporting young fashion designers, and the upcoming Cumulus conference, our interview covered a variety of subjects from the challenges faced by the Hungarian fashion industry to the foundation of a fashion republic.

Recently, Budapest has been home to several fashion exhibitions, such as Fashion & City at the Kiscelli Museum and Hungarian Brides at the National Museum, primarily approaching fashion from a historical perspective. Through these instances, or perhaps others, how do you see the current state of fashion discourse and the representation of the fashion industry in Hungary?

In the realm of museum studies, it is apparent that there are roughly two curators – Judit Szatmári and Ildikó Simonovics – whose focus also include fashion, and who are consistently working towards making more exhibitions of this nature happen. Something that has come up again and again is whether Hungary will ever have a fashion museum. The biggest question in that regard is what we think of the archiving of fashion goods or their memory-political implications. Fashion curators primarily work from general cultural heritage archives, where the focus is on textiles and costumes rather than fashion itself. Fashion does not necessarily equals textile and costume. Nevertheless, I believe there is an inclination towards professionalisation in fashion museology and even fashion science. For instance, within the MOME Doctoral School and rural doctoral hubs, there are two or three experts specialising in fashion in their academic pursuits. I wouldn’t say that it is a cohesive processes; rather, there are individual ambitions that people may or may not succeed in securing funding for. This is all a distinctly Central Eastern European phenomenon, everything here follows the same pattern: we plunge in, and then there’s no way knowing if it will be possible to keep on. For example, during the time I taught communication in Debrecen, we were organising the Debrecen Fashion Festival, now overseen by fashion designer and my doctoral student Dóra Balogh. It’s evident that securing funding isn’t as straightforward anymore; events get postponed, cancelled, or downsized.

The absence or instability of institutionalisation may also stem from a lack of understanding of what fashion science is about.

I believe there are several factors behind this. Fashion science faces the same issues that my colleagues at the MOME Institute for Theoretical Studies have identified when researching design culture. I reckon the unfavourable reputation of fashion complicates matters: at least in Hungarian culture, the social standing of fashion goods is considerably low. Designers engaged in other sectors, such as aviation or automotive design, have more prestige than fashion designers. Furthermore, there is a notion – mostly prevalent in certain researcher circles – that being involved in fashion means you have unlimited funds.

No one can see the structural issues that cause the fashion industry to be underfunded: sources supporting academic research often dismiss it as frivolous, while the market shows zero interest in finding out what scientific concepts could best describe the field.

Not to complain, seeing as I’ve come to make a living from it, but it’s not trivial whether this is something you can do or not. I’ve given a lot of thought to where my obstinate tenacity and tendency to bury my head in the sand in this regard is coming from. I’m second generation intelligentsia, which means I’ve witnessed how an intellectual career is built, which led me to believe that perhaps one day, I would have the opportunity to dedicate myself entirely to fashion. I didn’t mind having to deal with a myriad of other things in the meantime, understanding the need for flexibility in this field. I completed my PhD in 2009 and joined MOME in 2022 – in the interim, I felt I always had to justify myself for being in fashion. I’m not trying to get sympathy here, I’m only trying to explain how the institutional framework works, where you need to be patient and not to expect instant recognition.

Quotations from author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (left) and art historian Linda Nochlin (right) in Dior’s 2017 and 2018 spring collections // Source: Daily Front Row, Vogue

You approach fashion from an interdisciplinary perspective, primarily through the lens of media studies. In your book titled Fashion Redesigned: The Media Functions of Contemporary Fashion, you raise a compelling point about how through the migration of fashion to social media platforms garments become detached from the human body, transforming them into an entirely new medium. How does this process of virtualisation impact the material aspect of fashion and industry operations?

I believe there are two forms of fashion prevalent today. One is perfectly virtualised fashion, which, within a semiotic paradigm, generates infinite meanings and maximises self-expression. I often assert that fashion is media today – in the most complex sense possible. This is evident in prominent brands, where even the minutest statements of identity politics are continually expressed through clothing. Labels such as Indigenous American, feminist, Generation Z, radical, etc., along with their various combinations, render brands highly specific in terms of identity politics. Today, this is possible because social media platforms enable even the most specific identity-political frameworks to be visually expressed. At MOME, I’ve learned not to consider these phenomena fashion in the sense of design activity because, as media, their role is to position meanings. A communication expert, an influencer, or a celebrity is often better qualified to do this than a fashion designer. Conversely – and I consider MOME to be a strong advocate for this – fashion is a design activity rooted in textiles and taking shape in craft with a myriad outputs from clothes to artworks. I find this area highly intriguing, and I’ve observed its visibility growing within fashion education. To “make media” you don’t need a fashion design degree – what you need is a desire to make a big statement and have compelling visual cues to represent your style. I don’t see this as harmful, rather, we need to acknowledge that it mobilises competencies not traditionally associated with a conventional design approach. I initially started working with fashion due to my fascination with its identity-political implications. However, the way the world has changed since then requires identity politics to be placed within the context of human ecology.

In terms of fashion education, I wonder to what extent it follows changes in fashion. How perceptible are contemporary changes in fashion within the educational framework and the mindset of young designers? How much do the latter’s design practices reflect the changes?

This is a very tough question. The way I see it is that there are fashion education programmes – even in Hungary – that began churning out fashion degrees and fashion designers to dress the celebrities of a highly mediatised world in cool clothes. This falls under the category of fashion as media, where people are trained to speculate with meanings. I don’t think it’s a good idea to separate this approach from the traditional goals of classic fashion schools.

On the other hand, what I see is that fashion schools that teach tailoring techniques, materials, textile handling, or ethical design processes, necessarily have little clue about fashion as media – these two areas simply tend to be incompatible.

Ideally, they should complement each other, but reconciling them is challenging. It is often said that science progresses at a slow pace; similarly, I believe fashion design is also a slow process, it is just forced to work in a market environment that fails to acknowledge this.

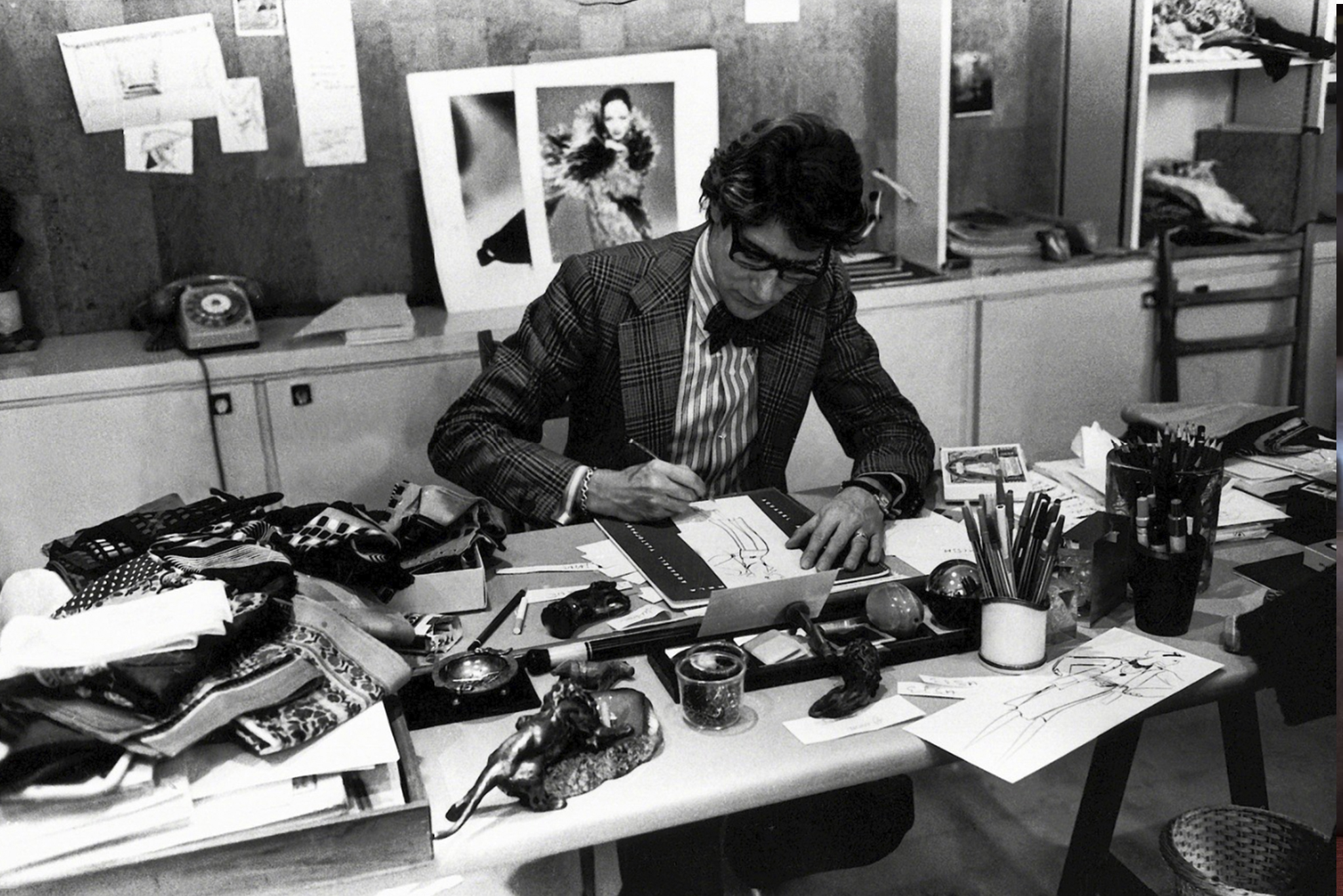

Yves Saint Laurent – The Couturier at Work in his Studio 5 Avenue Marceau, Paris, 1976 // Source: artsy.net

It is precisely the market environment that is affected by social media. Your book discusses extensively how social media platforms push fashion labels to work at full capacity, in turn pushing designers to their limit, and inundating consumers with waves of new collections. Criticism of this modus operandi comes precisely fashion designers and consumers, leading to a clash between vested interests from the top and emerging resistance from below. How does the fashion industry respond to tensions resulting from this dynamic?

Since the 1980s, the infiltration of capital into the industry has transformed creative directors and designers at fashion houses into big-time market players. If designers are tasked with generating millions of dollars in profit every six months, they might as well forget everything they were taught at university about creativity. In academia, six months is often the time dedicated to just developing a basic idea – we teach students to engage in slow thinking, which results in collections with genuine value. After completion of the training, however, designers are faced with a conflicting set of expectations, demanding quick turnarounds in a matter of months or even weeks. The industry responds by increasing capital speculation, leading to growing pressure on creative professionals.

In January of this year, some thought-provoking data were released: the richest person in the world currently is no longer Elon Musk, but Bernard Arnault, the owner of the Vuitton conglomerate. While luxury goods production may not be completely synonymous with the fashion industry, it is evident that one can amass considerable wealth from the manufacture of luxury items compared to the tech industry.

Though perhaps isolated, these are telling data, especially when all we hear is that the real money is in technology. At the same time, there is a subtrend in fashion, in which many designers sacrifice visibility when it comes to locally sustainable, small-scale brands. They don’t care about appearing on the cover of Vogue, but take great pains instead to maintain high standards of tailoring and material know-how. In a strictly economic sense, these businesses may not be regarded as part of the industry, as the way they operate is closer to historical guilds and cater to an extremely niche market. In the 1980s, even Yves Saint-Laurent could boast about emphasising craftsmanship behind his garments; today, few designers at major fashion houses can afford to do so any longer.

You mentioned that the luxury industry does not equal the fashion industry. The Hungarian Fashion & Design Agency (HFDA), as a state actor supporting the national creative sector, however, prominently advocates for luxury products and international visibility. How effective do you believe this state involvement is in the Hungarian fashion industry?

This is indeed a difficult question. We need to realise, just as the film industry has already done so, that in countries with a small market it’s impossible to live entirely off the market. I strongly believe that the pioneering role of the HFDA in the fashion industry should be rewarded, precisely because this sector has previously lacked funding. Fashion, just like pop music and film, is a cultural industry where aesthetics evolve within market and industrial production frameworks. The HFDA was established to acknowledge this and to bolster networks capable of revitalising the market and the industry landscape. However, as with any centralised process, there are questions around what is included in the funded spectrum and what is not. While the HFDA’s strategy seems to be geared towards the Italian market, that particular geopolitical area has distinct rules which cannot be universally applied to the global industry. Additionally, the HFDA must operate within the confines of the current Hungarian market. Most national brands follow the classic consumption model, tailoring their strategy towards female earners with autonomous careers. Despite a few notable exceptions (Zsigmond, [Unreal] Industries, etc.), the strategies of most Hungarian brands are targeted at young female personas. While this trend is visible also internationally, I believe there is greater scope for a broader definition of personas. In Hungary what you have is purchasing power and demand for fashion, so these are the most relevant considerations. I would welcome more radical departures from this established pattern.

Staying on the topic of the HFDA for a little longer – your book discusses how those in vocational fashion industry training often receive less recognition than fashion designers. Despite the release of an article series on the textile industry crisis autumn last year, the HFDA is launching a programme to promote fashion and design industry training, in which you are also involved as a professional mentor. Undoubtedly, there is a need for fashion industry professionals, but beyond the programme, what prospects do they have?

The series on the textile industry effectively highlighted the common understanding among fashion professionals that the light industry ceased to exist in Hungary after the regime change – it’s hard to add anything to that. However, I firmly believe that if there are people who are passionate about the field, the individual aspirations will converge and lead to the development of new solutions. Not just the light industries, but also the entire fashion industry needs to pull itself up by its bootstraps. Though I have no idea how or to what extent this will come off, we need to acknowledge that the status quo has been a failure from the get-go. If vocational training and its educational significance can get some spotlight now, it could launch the development of a currently non-existent fashion culture. Say, young people may gradually realise that getting their clothes from the same fast fashion stores as their classmates is not good and develop a desire to create their own clothing. Or if they can’t, they should have the option of finding people to help them. In this world of millions of amateur “fashion designers”, professional expertise can go a long way to help realise creative ideas – this concept of co-creation is already prevalent in international fashion education.

In this collaborative framework, designers work with potential consumers to come up with concepts together. This requires boldness from the consumer to start seeing themselves also as bodies, and humility from the designer to acknowledge the shared work in conceptualising the body.

As an educator and idealist, I find this approach both viable and appealing.

The fashion show of Terike from Budapest at the TEDxLibertyBridgeWomen conference, 2023

Co-creation or grassroots collaborations are emerging in various fields as responses to economic vulnerability and social crises. Personally most examples of this I see are in visual arts, but if I’m not mistaken, Terike from Budapest shares similar goals. From a historical perspective, what affinity does the fashion industry have for developing solidarity-based collaborative systems?

In the early 20th century, several fashion houses were established under the leadership of prominent female designers, such as Lanvin or Vionnet. These women built their careers from scratch, relying on their own resources rather than existing wealth and personally experienced the challenges of balancing work with responsibilities like raising a child as a single mother. As a result, their labels had highly developed union systems. For example, Vionnet provided free monthly medical check-ups for all its employees. They created a very humane work environment, made possible by the loyalty of their clientele established within the moneyed aristocracy of the time. At the time, fashion brands didn’t panic about losing image-oriented customers the following month who want to show off more exciting content on their Instagram pages. So, while I understand the difficulties that brands face today, I deeply admire the early fashion industry built on union logic, and I regard it as exemplary.

If we try to interpret trade unions in today’s terms, what specific opportunities does a creative community and interest group like Terike offer?

When we started brainstorming with Szarvas Valentin about Terike, it wasn’t necessarily the fashion industry that I drew on for inspiration, but rather the self-sustaining strategies of gastronomy. The key to these strategies is always to think small and stay small, so it’s crucial not to fully engage in the visibility competition. Self-sustaining small farms can fund their own industrial activities from start to finish. The production process of fashion items is similarly circular, as first, the textile is produced, then the garment is made, and then the textile returns to the beginning of the process. Based on this, you could invent an “industrial commune” where each member’s expertise is valued at their own level. I may be incredibly naive when it comes to this, but I reckon that if we grow the plant from which we make the textile material, oversee the weaving and design of the fabric, and work on the development of the sewing patterns and creative ideas, then essentially, all the separate parts of the process can be interconnected. I enjoy listening to Zoltán Pogátsa’s show, the Pogi Podcast, where he extensively discusses initiatives bypassing capitalism. One time he spoke with the people who came up with the idea of Krishna Valley, and it was mentioned that as they approached retirement, one couple in the community decided they wanted to become self-sufficient in terms of textile use, and now their family only uses textiles they produce themselves. Granted, this is just one family for now, but it demonstrates how the design process could be integrated into this model. In the Krishna Valley, you can see unique dressing techniques; their objective isn’t to integrate textiles into fashion concepts.

This solution particularly resonated with me because I often ponder how to make fashion design a less solitary endeavour, how it could be more inclusive to the consumer – and now I’ve realised that textile production is essentially a communal practice. If we approach the process holistically, what we get is a beautifully functioning “fashion republic”.

Just as we’ve become mindful over the past two decades about what we put into our bodies, we also need to prioritise what we put on our bodies as our second skin. The importance of the textiles we wear, along with the food we consume, is another aspect that cannot be emphasised enough.

This put me in mind of the projects of the Solidarity Economy Center. Have you come across any reference points like this? Where do you stand currently in terms of organisation?

We’re currently at a stage where the objective isn’t immediate profit, but rather to devise a system in which, alongside our autonomy, the most valuable aspect of our profession can remain intact. We can relate to textile design students best who strongly believe in the central role of tailoring – in other words, until you are able to make a garment expertly, you should forget about creative conceptualisation. The 20th-century fashion designers who I find the most inspiring are the ones who were innovative in tailoring. The way I put it in class is that they do not merely create silhouettes, but rather reinvent existing tailoring solutions. For instance, the Antwerp Six, Martin Margiela, or even Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga truly understand tailoring, the form language of fashion. I believe that when the subject of sustainability and the idea of reworking garments come up, we often overlook what fashion design skills are essentially about – that designer craft has the power to enhance a person’s silhouette. If we throw this out the window and let people buy standard sized pieces from fast fashion stores and have their existing garments altered, the culture that has contributed significant creative potential to global human values for two or three hundred years will be in a precarious position. We say “Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater” – in this case, the baby is tailoring expertise and we have to take special care not to “throw it out”.

I often reflect on how odd it is that humanity has reached a point where we do a lot of low-quality work, eat a lot of low-quality food, wear a lot of low-quality clothing, despite finally being in a position to prioritise quality. Terike is an embodiment of this aspiration.

We’ve previously discussed your respective roles as a researcher and educator, including your leadership of the Centres and Peripheries section of the Cumulus conference organised by MOME. Based on the applications, what main directions and important topics can you see emerging?

The goal of the call was to shine a spotlight on postcolonial modus operandi and their critique. We assumed more applications would include a criticism of the functioning of capitalist markets, but there were not many of those. However, we received such an abundance of papers related to education that we needed to set clear boundaries to prevent this centre-periphery issue observed in education from dominating the entire section. Perhaps this trend has emerged because the conference is primarily directed at the academic community, for whom the centralisation of education is the biggest concern. Some articles gave me the impression that we we are turning upon ourselves – though it may be intentional. For example, receiving a paper showcasing collaborative work between Indian and British students from one of the world’s leading fashion schools, formulating a criticism of postcolonialism from a central standpoint, feels contradictory to me. In addition to education, another significant trend is the critique of dichotomy, involving an attempt to approach the issue of centre-periphery through systems theoretical concepts such as the Global North and Global South. We were pleased with these submissions and hoped for more of them. Another large group focuses on spatial structures, with several papers illustrating the workings of postcolonial logic in tangible, physical spaces, exploring the dynamics of centre-periphery through the design of a residential building in Beijing or on a map of Berlin.

// /

The cover is part of Judit Spanyár’s series titled Dressed for brutalism.