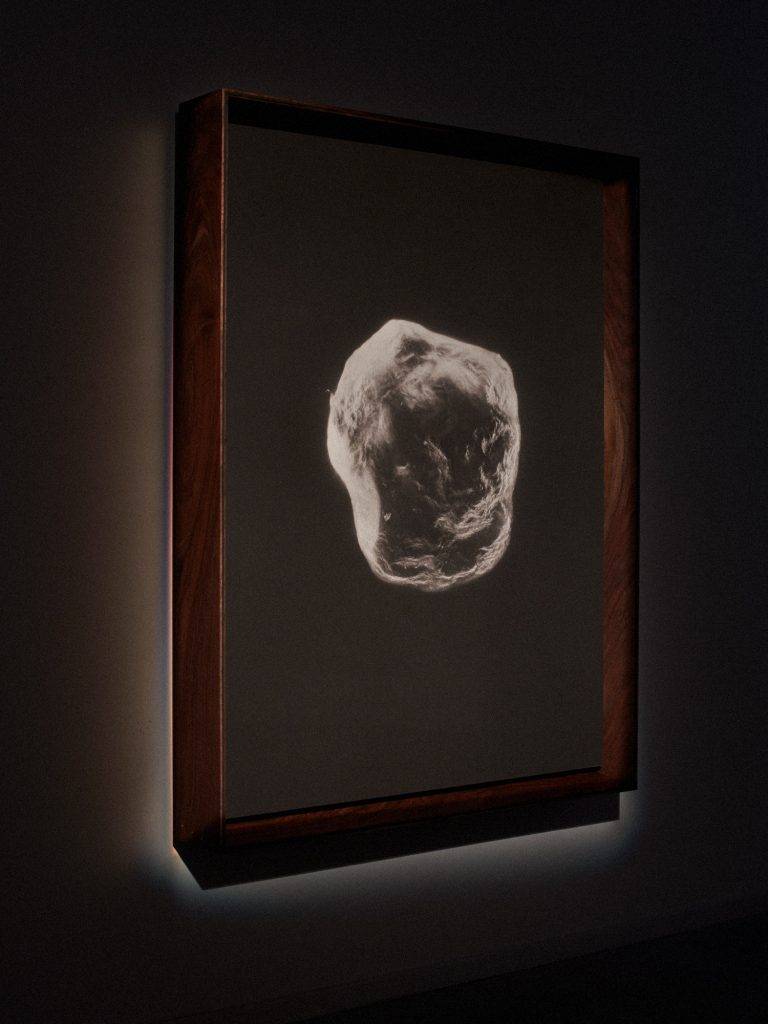

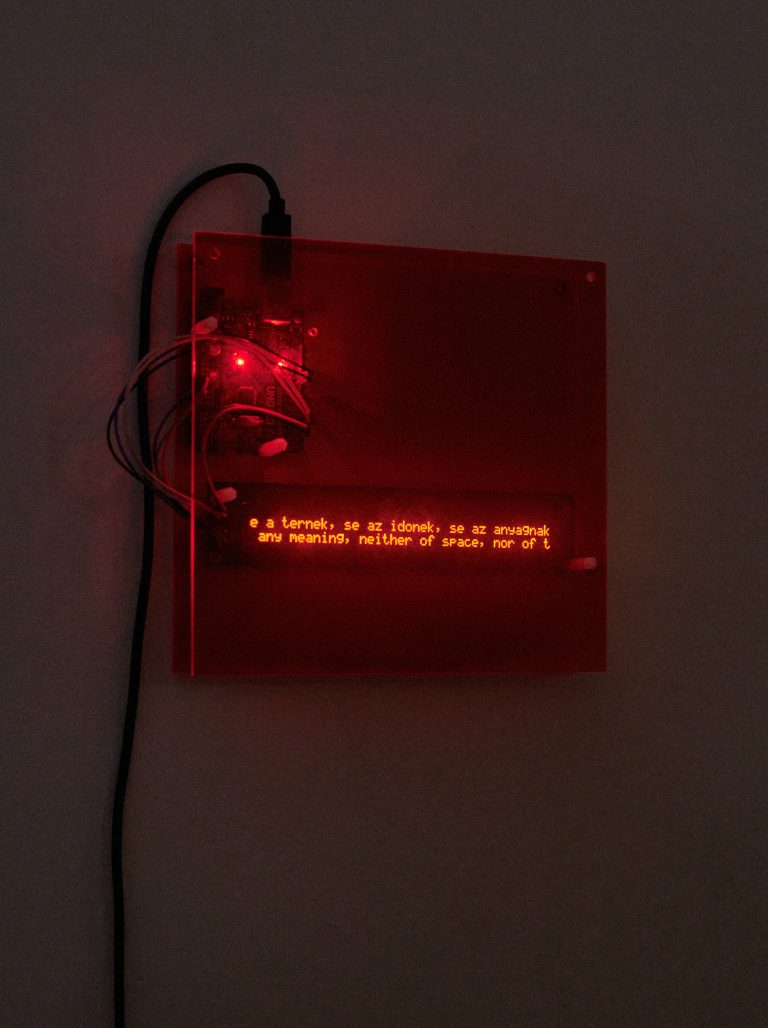

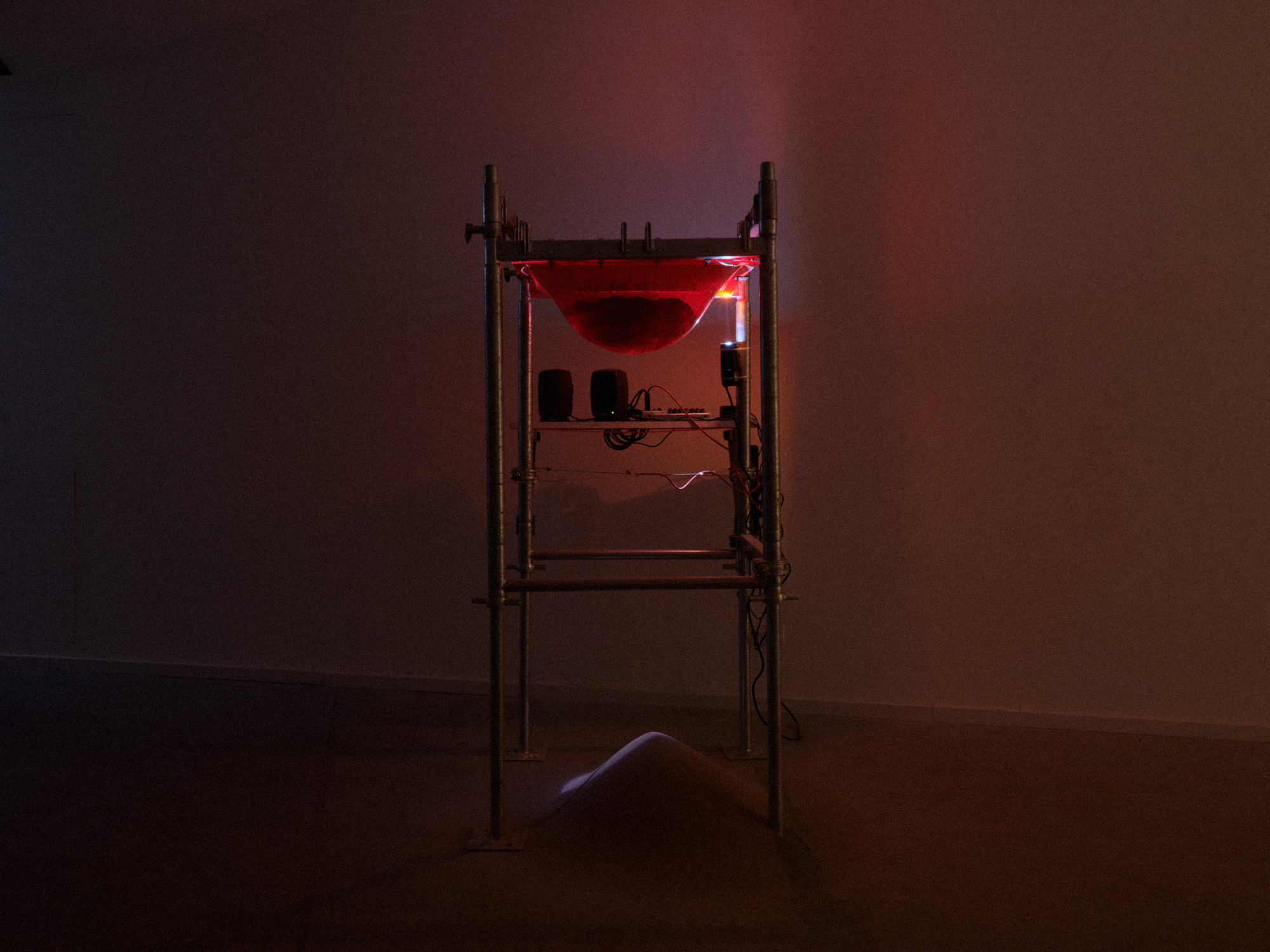

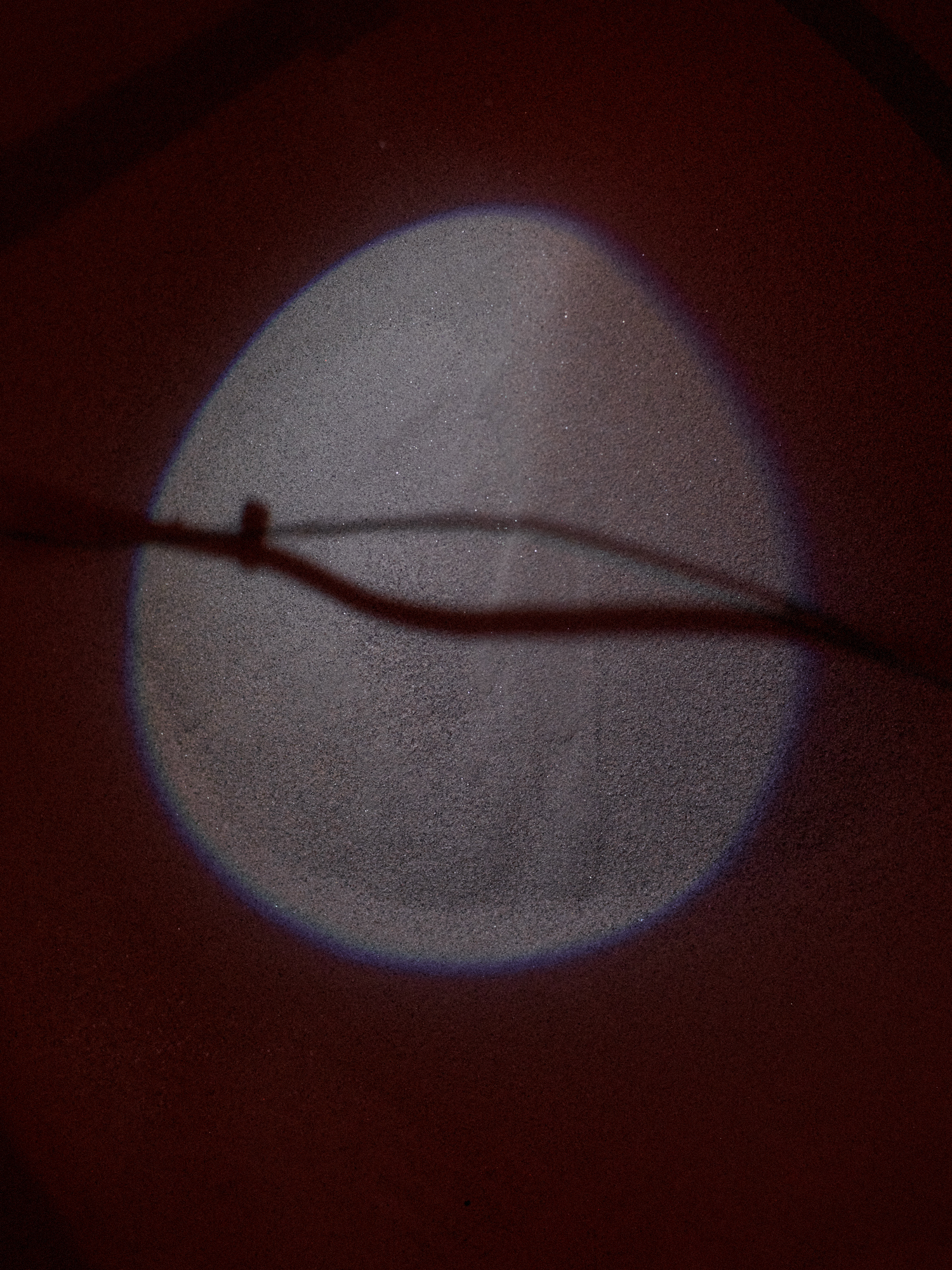

Notes on the Sand Gears – On the Grana Arenaria exhibition

“Throwing sand in the gears” is an expression commonly used to describe something or someone that hinders the smooth operation of a system. But what happens, we might ask in the spirit of the new exhibition Grana Arenaria of the Szüdzügia collective consisting of Máté Hulesch, Balázs Máté, Márton Emil Tóth and Csenge Vass if the gears consist entirely of grains of sand? What if the proverbial gears, as a closed system, is nothing but a collection of sand grains, working solely due to the interplay of these grains? In this case, could there be something else that, when mixing into the grains of sand, disrupts their smooth interplay? Can we imagine at all an emptiness or void among the sand grains, a free volume fraction or negative space, that causes this entire machine to appear porous and hollow to us?

But let’s talk about something (seemingly) entirely different, like cheese – for instance, Emmental. There is a metaphysical dilemma, as old as the universe itself, comparable to the “chicken or the egg” question: are the holes in Emmental cheese still part of the cheese or not? Although these tiny air bubbles that burst inside the cheese are constitutive moments in the fermentation process, crucial for the formation of the cheese and its final volume, they do not count towards the weight of the cheese – in other words, we do not have to pay for them separately at the cheese shop.

In the spirit of philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, we might ask whether these particular gears, which we might call the sand gears based on the installation of the Szüdzügia collective, or simply the universe by its common name, contains anything other than grains of sand. Is there anything else outside these sand-filled gears? Do they have an outer shell or surface, and if so, are there other gears beyond them, filled with sand or perhaps something entirely different? If so, what form do they take viewed from the outside? Or do they only have an inside? If they only have an inside, does this interior have a discernible form? Is there an inner wall and space between the sand grains, or not? Do these sand grains move and interact with each other, or do they float in place for all eternity?

The earliest attempts to systematically ponder such questions in human history can be found in ancient Hindu wisdom, the philosophies of Buddhism and Jainism, and the pre-Socratic Greek philosophies, which developed various atomistic theories and explanations of the world. Atomism itself, as is well known, posits that all matter in the universe consists of small, indivisible, and indestructible particles called atoms. This concept was developed, among others, by the philosophers Leucippus and Democritus in the 5th century BCE.

Atomism represented a revolutionary innovation, as its proponents sought to uncover and understand the nature and structure of matter without resorting to mythological or supernatural explanations. They believed that atoms are eternal, indivisible, and indestructible particles, whose differences in shape, size, and weight accounted for the various forms and properties of visible objects in the world. Most atomists agreed that, in addition to atoms, there is an empty space or void in which atoms move. This void is essential because it allows atoms to constantly rearrange themselves; without it, movement would be impossible as there would be no space for atoms to move into. Thus, atoms are in constant motion within this emptiness. The differences in the properties of materials are explained by the variations in the shape, arrangement, and relative positions of atoms. These movements and interactions lead to different combinations, resulting in the myriad objects observed in the world. According to the atomists, the movement and interaction of atoms are dictated by natural laws and can also happen randomly. This randomness, combined with necessity, can lead to the creation and transformation of objects in the universe without any divine intervention or predetermined order.

All this has immense philosophical implications regarding free will, the nature of material and non-material existence, and the very knowability of reality, and significantly influenced later scientific thought, particularly the development of modern chemistry and physics in the 17th and 18th centuries – not to mention the Szüdzügia collective’s current exhibition, Grana Arenaria.

But one might rightfully ask, what relevance does all this have to art? Put more simply: what is the relationship between art and the objective truth of science? As formulated by György Lukács’s rather bluntly, “artistic representation undertaken for scientific purposes always results in pseudoscience and pseudo-art, and the ‘scientific’ solutions to specific artistic tasks similarly produce pseudoscience in content and pseudo-art in form.”

The compartmentalisation of various disciplines has become outdated in light of contemporary crisis theories. Reality has become too complex, and the political, social, ecological, and economic crises threatening our planet and humanity – on planetary and local, microscopic and cosmic scales alike – have become too urgent to separate science and art from each other.

However, art that is subordinated to external goals, such as the teleological service of scientific rationalism, also comes under scrutiny. Artistic representation should not serve scientific or social purposes; instead, it must continuously renew its own autonomy and remain true to it, which essentially means abandoning representation itself. This is why American art theorist Clement Greenberg asserts that “It has been in search of the absolute that the avant-garde has arrived at ‘abstract’ or ‘nonobjective’ art – and poetry, too. The avant-garde poet or artist tries in effect to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape – not its picture – is aesthetically valid; something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars, or originals. Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself”. This is why avant-garde art, in its search for possible subjects, often returns to itself, beginning to elevate the forms, poetic decisions, and modes of art itself into themes.

So, good art not only renders the imperceptible perceptible, thereby making the inconceivable imaginable and comprehensible, but it also reveals something about the manner in which it accomplishes this, all the while doing so as if no one else had ever attempted the same. It’s important to note all of this in the context of the current exhibition, as here, the age-old issue of the atomists is thematised in such a way and with such conviction as if no one had ever attempted it before. This will be the basis and the prerequisite for everything Boris Groys claims about art being a non-obsolete technology, namely that in relation to the developmental principle of techno-scientific production, one of the main ontological differences of art lies in the fact that newer works of art do not displace or overwrite preceding ones. While Einstein’s theory of relativity superseded the Newtonian worldview, for example, Picasso and the Cubists did not surpass the achievements of Cézanne in any way. Art, therefore, functions as sand gears, continuously welcoming new grains of sand without displacing older ones.

What I mean to say is that artists are evidently grains of sand in the otherwise smoothly functioning machinery of goal-oriented rationality and efficiency. I believe that the exhibition opening by the Szüdzügia collective, with its shared thematic realms of time, space, and matter, is a perfect example of the necessity for such grains of sand. It also splendidly illustrate the productive movements and interactions that can occur among these grains of sand when there is a receptive space in which they can form an alliance with each other and with the world, whether it be an exhibition space or their alma mater, the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, which is currently celebrating its 25th anniversary. Let this exhibition opening be a celebration of the grains of sand slowing down the efficiency of the gears and the open space that embraces them.

// /

Photo: Balázs Máté

Graphics: Áron Lődi

Special thanks to: Tamás Bene, Júlia Gáspár, Hedvig Harmati, Máté Janky, Áron Keve Kiss, Vilmos Steinmann, HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences

The Grana Arenaria exhibition is realized on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the MOME Doctoral School, with the support of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design Foundation.