“It’s good to be here, but there’s also a sadness in me” – Photos of Hungarians in Berlin

Golden mediocrity. That’s what comes to mind looking at Anna Franciska Legát’s series, Melancholy of Freedom. Golden, because I see eyes filled with hopeful, gentle courage. Mediocrity, because there’s nothing extraordinary in the whole scene. Familiar urban backdrops, rows of tower blocks built in the previous century, plywood furniture, patchwork tattoos, leather jackets, and woollen coats, Eastern European outskirts vibes instead of downtown glamour. And, of course, cardboard boxes used for moving. We might as well be in Budapest. This time, however, instead of two areas, two countries have become the interstice.

“We must admit that most of our theoretical knowledge is nothing but abstraction, logical exercise, and now that reality has struck us, that we are primarily emotional rather than thinking creatures. Slaves to our moods. And our mood is shaped by the situations and circumstances around us.”

– Lajos Kassák: A Man’s Life

A few years ago, headlines shocked us with the claim that London is the second-largest Hungarian city. In contrast, about as many Hungarians live in all of Germany as in the English capital. Therefore, Berlin is interesting not because of dry statistics but because of its unique role in the collective Hungarian memory. Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was a symbolic place: the end of melancholy, the beginning of freedom. A place where ideals are literally within an arm’s reach.

“We miss the illusion we had after the regime change when for a few years, we truly believed that real change was coming.”

It might be oversimplification, but in some ways, the perspective is similar to that of the 1980s: welfare democracy, existential security, a vibrant life, and progressive thinking. Moreover, Berlin is culturally and geographically close enough that moving doesn’t feel like a leap into the void. Yet it’s just far enough that one must say goodbye to the life at home, everyday routines, comforting memories, friendships, and any sense of sanctuary. Franciska skilfully focused on this tension of psychological distance. How can something be both near and distant? Familiar and unfamiliar? Uplifting and suffocating?

“The first days were spent in a state of floating, then melancholy started to set in. Leaving your home country takes a heavy toll on a person. When I visit home, sometimes it physically hurts to come back.”

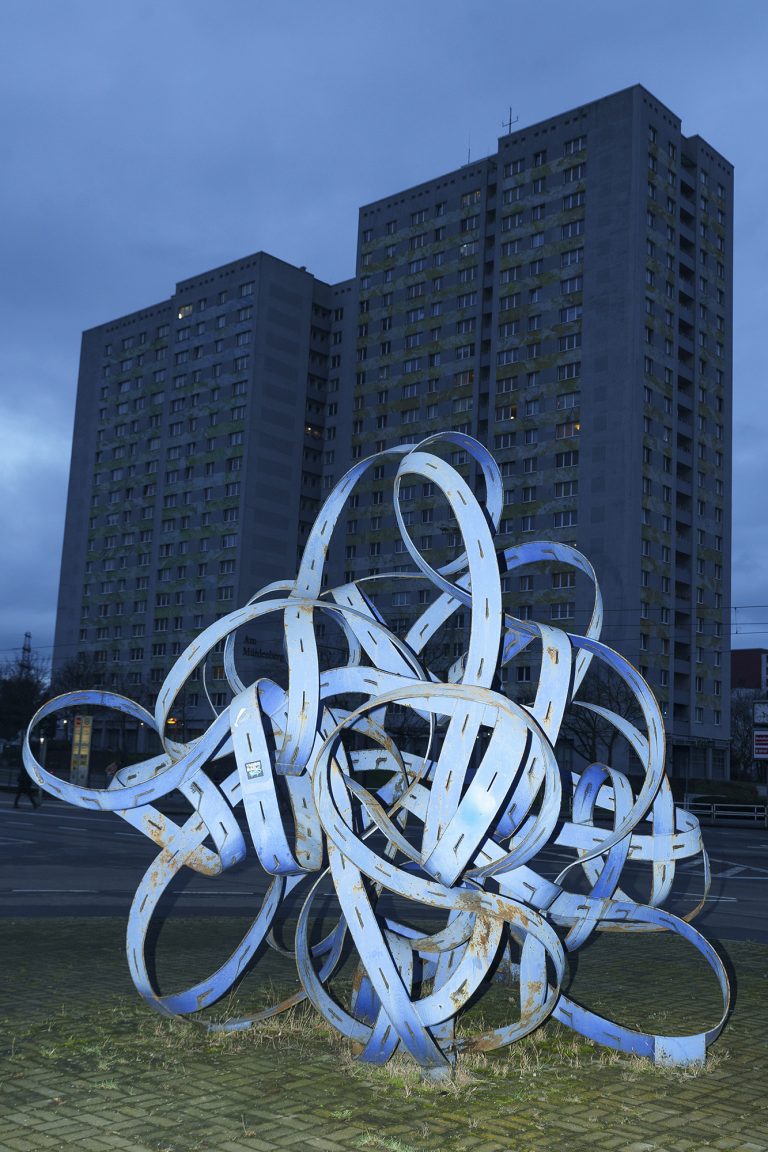

The photos in Melancholy of Freedom are halfway between documentary photography and staged photography. The models are photographed in their own environments, at locations significant to them, with compositions that sometimes express anxiety and loneliness, and at other times evoke a sense of carefree freedom. This ambivalence extends to the locations as well, such as well-maintained spaces, parks, lakes, but also industrial landscapes and uncomfortably narrow staircases. The city is just a backdrop; instead of typical Berlin motifs, we are plunged into a dreamlike dimension complete with not only symbols of wealth, from Mercedes logos to new-build apartment complexes, but also the mementos of the Eastern Bloc – rust belts, graffiti, and rundown pubs.

“I often felt more like a stranger in my own country. Abroad, it’s clear that I am an outsider, and that is comforting.”

Franciska always began her work with recorded interviews, which turned into informal conversations. Since she was looking for common points and overlapping experiences rather than unique stories, she incorporated some enlightening quotes into her concept. The quotes have became integral components of an installation, equivalent to the photos. These annotations often reveal such disquieting depths about migration that could hardly fit on billboards. Instead of oversimplified slogans, they speak of irresolvable contradictions.

“I miss this Eastern European vibe, which is somewhat depressing yet somehow liberating. This dry yet vibrant, self-deprecating humour, marked by traces of the Holocaust, fascism, Bolshevism, and all other kinds of oppression, and wrecked by wild capitalism, has no equal.”

Naturally, there are many ways to talk about emigration, cultural differences, home, and homeland. One thing seems certain: it’s a current topic, but not because it is a political or economic issue. Hope, uncertainty, a sense of loss, and alienation – these are the stakes. Perhaps that’s why I felt an inexplicable sadness looking at the photos in the series. It was as if I saw my own friends, relatives, and colleagues. True, they tried their luck in Los Angeles, Helsinki, London, or Lausanne rather than in Berlin, but I think the point is the same. Rarely does one leave anything important behind out of joy.

// /

This project was created at the Photography MA programme of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, with Gábor Máté as her supervisor and Judit Gellér as her consultant.