“I Don’t Agree That Design Is a Universal Cure-All”

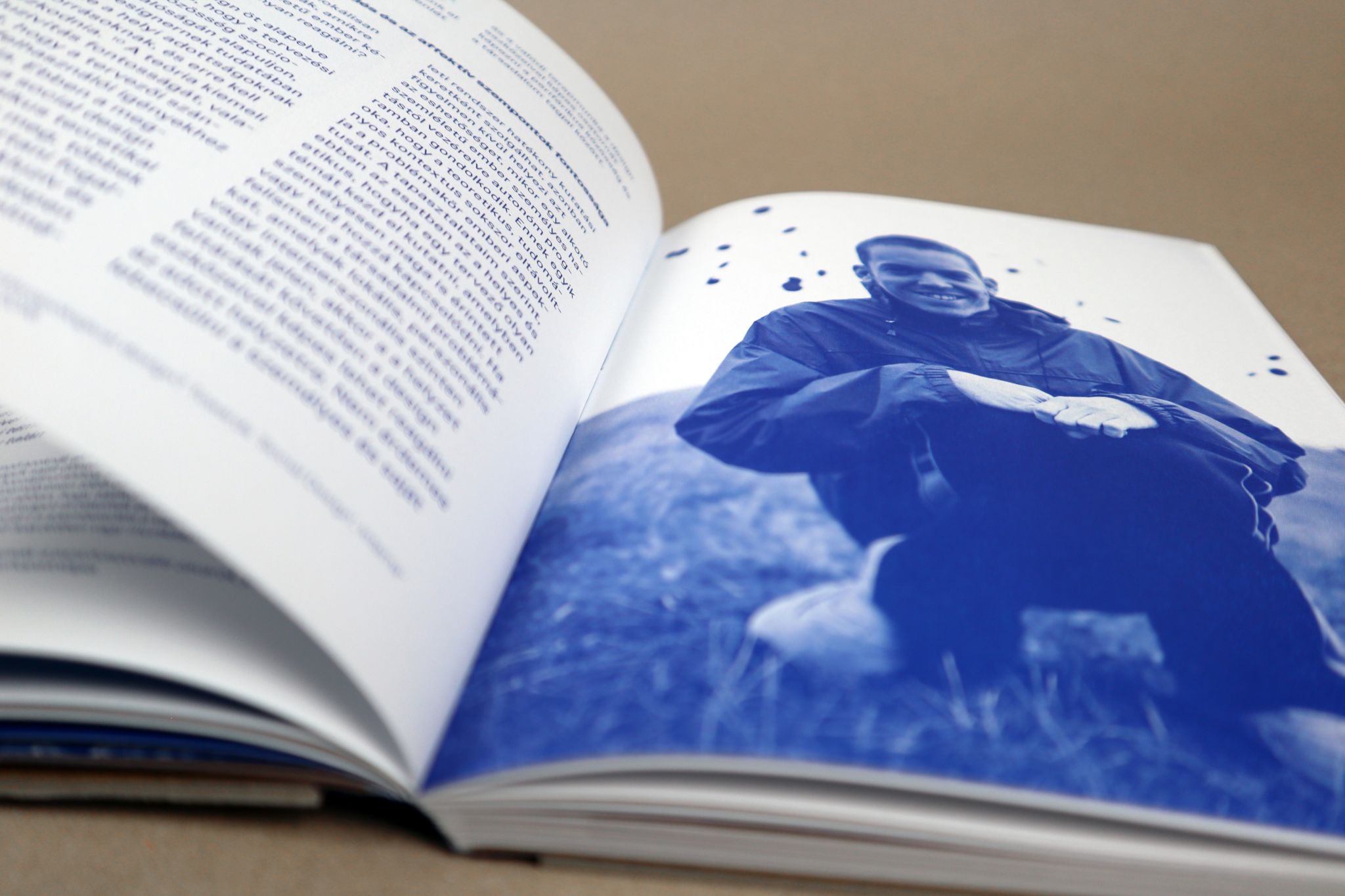

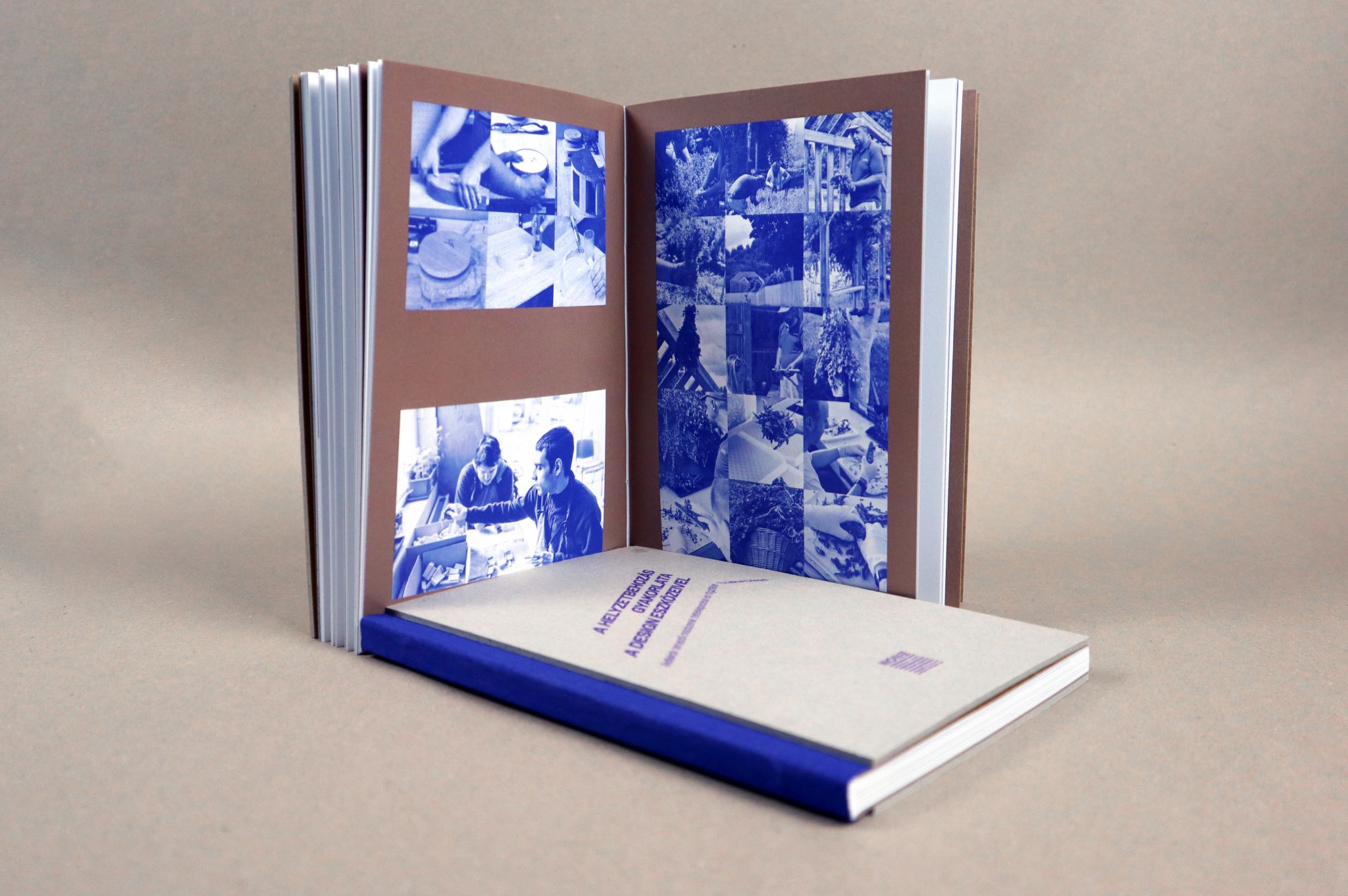

MAACRAFT, a social enterprise founded in 2012 as the creative workshop of the Miskolc Autism Foundation, operates under the leadership of Dániel Szalkai. Over the years, Dani has spoken on various platforms about MAACRAFT’s operations, his personal connection to the initiative, and the workshop’s day-to-day processes. In this interview, however, the focus shifts to the societal role and responsibilities of design, as well as his recently published book, The Practice of Empowerment Through Design.

Your book’s release announcement mentioned that this publication is something you’ve owed yourself for a long time. What inspired you to share your experiences and insights in book form?

Life had a way of turning the past fifteen years into a constant rush. Working in the non-profit sector demands relentless repositioning, a search for purpose, and immense effort. I simply hadn’t had the opportunity and time to write down the thoughts that drive me as a creative thinker or to lay down the professional foundations that I bring to projects. However, after several years of running the MAACRAFT workshop, I began to notice that many of our projects represented innovative accomplishments in both the design and the social sectors. It was after the COVID-19 pandemic that I seriously considered taking stock of these accomplishments – not least for resource acquisition purposes. Maintaining both a creative practice and a community requires submitting lots and lots of grant applications. To provide MAACRAFT’s team with proper working and living conditions, we need resources. Over time, I realised that many of our grant applications failed because we lacked material that comprehensively presented the workshop’s professional activities. I was constantly seeking new paths and juggling too many tasks, which fragmented my creative process. By now, I’ve established my core principles, and I wanted to consolidate them into a publication.

In addition to the MAACRAFT community, you’ve recently started collaborating with other groups.

That’s true – I’ve moved somewhat away from the community I previously worked closely with. My doctoral project marks a shift, as I’m now focusing on addiction and individuals struggling with substance abuse. I work with a community of people who have other challenges in life than cognitive difficulties; their condition is more of a psychological disorder or, as they define themselves, “mental illness”. This dynamic differs significantly from my experiences with the MAACRAFT community, with a slightly different starting point. While design in the context of intellectual disabilities or autism integrates into skills development, for individuals with addictions, it becomes a tool for addressing societal misconceptions. I’m currently working to apply the knowledge I’ve gained to this new community while still adhering to the principle of empowerment highlighted in my book’s title.

How would you define the concept of empowerment? What exactly do you mean by it?

Empowerment could even be understood as compensating for disadvantages. There are invisible individuals – those excluded from consumption, undervalued, or outright undesirable in mainstream society. In the book, I describe these groups as being in a “state of inertia”. Design has the potential to identify and address these issues by becoming embedded in these situations. I disagree with the notion of design as a universal cure-all because it cannot resolve the massive, structural socio-economic and cultural challenges we face.

Instead, I believe in applying the sensitive, reflective tools of design and creative arts to specific situations. These tools can impact representation by addressing inertia and a lack of resources, empowering affected communities. This way, design can help assess perception of a social group and manage the process of moving people from a state of passivity to active engagement.

Why do you think design is often seen as a “universal problem-solver”? Where does this perception come from?

It’s trendy for designers and artists to address social issues – it makes a product work more marketable. It is an important aim for designers to reflect international trends within a local context, but this in itself isn’t enough, especially when their claims don’t match reality. While consumption will always be a given, design can help us approach it with a different mindset. In welfare states like Denmark or the Netherlands, where equality efforts are more advanced, design culture can align with politically-backed social projects. Design is a toolkit that works both in industrial contexts and in addressing the needs of marginalised social groups. It can yield exciting solutions, but these cannot be transplanted wholesale into Hungary. Here, we are trying to cultivate a flourishing plant in entirely different soil – it takes much more effort for that plant to even sprout. Opening an equal opportunities café in the city centre that represents disadvantaged people living in segregated areas doesn’t solve the underlying issues. Unfortunately, in Hungary, this is often how it’s presented.

In Hungary, empowering marginalised groups is indeed challenging…

The branding of vulnerable communities is somewhat flawed, and we, as creative professionals, can do a lot to change this. When I encounter a community struggling due to a lack of resources, I do not want to pity them and then go back to my comfortable, warm home and privileged life. I want to see what’s possible and what I can offer to change their misrepresentation.

After a while, I grew disillusioned with the notion that design is merely about creating highly aesthetic objects in a competitive setting. I enjoy combining extremes, and I became fascinated by the possibility of applying design logic to contexts that are not inherently about competition.

You mentioned in your book that your methodology is rooted in the collective creative process. How challenging is this in practice? What is it like to work with the groups you describe in your book?

Many of the affected communities I work with, such as those living in residential care homes, already engage in some creative activity. However, the time and effort put into these processes – be it beadwork, weaving, or concrete casting – often don’t improve their circumstances but rather keep them in a state of inertia. The potential lies in initiating collaborative creative processes tailored to the abilities and resources of each community. Design can help adapt old knowledge and introduce new skills. Our focus isn’t necessarily on appealing to the paternalistic sentiments of mainstream society but on highlighting the activities and capacities of the affected individuals, and that heir skills can manifest in products that can later serve to symbolise the values of their community. This is a lengthy process of building trust, involving constant reflection, and taking steps forward and backward, given that some people are distrustful – it took me two years to get this idea of mine accepted. I mostly work with associations and foundations and they can be stagnant and resource-dependent. It’s not easy to motivate their leaders, because even if they find your proposal appealing, they struggle to break away from their familiar yet ineffective routines.

So, it seems you’ve experienced the downside as well. Have you encountered situations where collaboration didn’t go as planned?

Mostly, I work with groups where you can only do good, but there are times when you realise the limits of what rehabilitation practices can do and you need to come to terms with not being able to do more. These individuals live in closed worlds, and the joy of creativity appeals to them more than lofty ideas or the opportunities I aim to create for them. Their lives can truly change if they experience something new. However, it’s often inconceivable in many institutions that the affected individuals could visit a workshop, create something, and later see their work exhibited in a gallery, say in the Kunsthalle. On the other hand, empowerment can also mean we stop pitying them. In the book, I mention the “rag rug theory”: when people see an individual from an affected group create such an item, they often respond in a condescending way, like “Oh, isn’t it amazing they can even do that!” These communities deserve better. They shouldn’t be infantilised, but valued and provided with opportunities to thrive. Workshops like MAACRAFT are now beginning to be positioned as social enterprises, but it’s been a long journey to get here. The shift in perspective has gradually taken hold from abroad, so hopefully, over time, initiatives like this will also gain market significance in Hungary.

What feedback do you receive from those you work with?

To be completely honest, I don’t know what my work means to them. For example, I see my MAACRAFT colleagues as a community and I feel responsible for them, but it is better if they aren’t dependent on me, so the program can remain autonomous. My goal – and one of the reasons for writing this book – is to create a system that functions without me. It shouldn’t be a one-man show with just my face on it because they are the ones running it. I aim to guide these groups towards finding their audience and earning appropriate remuneration. Also, like I outlined in the book, to adapt the methodology to various communities.

I compiled my experiences so that we can examine the situation of people with disabilities – and other marginalised groups in Hungary – from a different perspective. At the same time, there are many other groups struggling to achieve autonomy or secure employment, and the methods developed at MAACRAFT can be extended to benefit them too.

// /

Dániel Szalkai is a student at the Doctoral School of MOME, his consultant is Dániel Barczai. His publication entitled “The Practice of Empowerment Through Design” was published by MOME within the framework of the New National Excellence Program.

Editing, graphics and photos: Zsófia Kérdy

Editing and proofreading: Judit Huszár

Professional contributor: Miskolc Autism Foundation

Portrait: László Sebestyén