‘It has to be good’ – An Interview with Zsófia Csomay

Zsófia Csomay is an Ybl-, Pro Architectura-, Prima Prize-winning architect, Artist of Merit, and honorary university professor of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. In 2021, she and her husband, Péter Reimholz*, were presented with the Moholy-Nagy Award. Together, they taught at the university for more than seventy-five years, and their works are just as much about thinking about the role of architecture as the buildings themselves. We talked about the award, the relationship between the old and the new, unrealised plans, star architecture and architectural ethics.

Zsófia Csomay with the Moholy-Nagy Award (photo by Máté Lakos)

She received the Moholy-Nagy Award in November from a community where she was a student in the sixties and later a key member as a lecturer since 1985. It was an emotional and meaningful award ceremony.

To tell you the truth, I’ve never been so happy about an award. The previous ones were awarded to me for a specific building, in competitions, except for the title of Artist of Merit and the Iván Kotsis Medal, which I also feel more deeply about, because it was a recognition of my work as an educator. But the Moholy-Nagy Award is much more than an award for me, because Peter and I really spent half of our lives at the university. Walking up the main stairs, I still get the same feeling I had when I first came to Zugliget to take my entrance examinations. As students, this school was our home: we worked here every single day from eight a.m. until 8 p.m. I also know who else have been given the Moholy-Nagy Award in the past… considering the list of names and achievements, I think the institution gave the award to me rather on emotional grounds, and nine-tenths of the recognition is owed to Peter.

Is it correct to say that, in addition to the buildings, reflecting on and writing about architecture plays an equally important role in your work?

This is particularly the case for Peter. In addition to having intuition and great talent, he always recorded everything and tried to put everything into sentences. We are not talking here about descriptions of artworks, but about the creation of a theoretical framework that was intended to reflect the approach to forms and structures. In this context, the idea and the building reinforced each other. In the sixties and seventies, our profession was characterised by a very high level of mature intellectual life and was not as diverse as it is today. We enrolled together to the Master School, where an architectural discourse was developed that captured everyone’s interest and which everyone contributed to. Peter, in addition to his wit and talent, was also extraordinarily lucky, considering that he was barely over thirty years old when he was awarded the Ybl Prize together with Antal Lázár for an already completed building. The fact that an architect who had graduated a few years before was given an assignment such as the DOMUS store was not at all usual, neither by today’s standards, nor at the time. In the first phase of Peter’s professional life, his engagement with theory is very clearly reflected in the completed houses. You could tell whether it was the theory that gave rise to the inception of the house or the house that gave rise to the inception of the theory. Firstly, I’m not this type of person, I’m much more instinctive, and secondly, we have three children, and I have tried to provide for them as best as I could with such a reflective husband by my side. As an architect, I also have an intrinsic system of architecture, but you need a special background and life situation to produce high quality writing.

Can these architectural ‘life situations’ still be the same today?

It’s an interesting question, because as the decades went by and the world changed, so di Peter’s perspective. Over time, the writings became few and far between and watered down. This was the result of a tangible process that took place all over the world, and which is a hallmark of the change between, say, 1967 and 2021. An architect, when given an assignment, must gain control over a certain mass, a construction, a material and a life situation. The role of the architect was and should be in fact that of conductor, but that is gone by now. Our profession is terribly exposed to the current circumstances, and today you need to coordinate with representatives from at least fifteen professions to complete a house. This is not necessarily a problem. It may bring an interesting new twist to our profession that will render forms and materials secondary in importance. The word ‘style’ no longer has any meaning today anyway. There is an ongoing change that may result in the disappearance of building-related nomenclatures that used to be dominant, and perhaps buildings will be built and used in a very different way. They will probably not be built for the long term, which means that the role of the architect will also be redefined. In the past decades, many fake and worthless buildings have been built, which quickly go to waste, both in the moral and physical sense. This symbolic wasteful star architecture, I hope will eventually fade out of the world.

Regarding the ‘old’ and the ‘new’, it was said at the award ceremony that “we should not build more houses than we need and take good care of the ones we have”. Shouldn’t we promote a culture of reinvention rather than novelty?

Firstly, we live in a city with a rich architectural heritage, and we need to protect it, because the identity of a city is, in my opinion, a matter of high priority. Secondly, old, homogeneously built houses are suitable for many more things than new ‘overly specifically’ created ones. They can take more, because at the time when they were built, there was an order of construction in place, in terms of scale and materials, that resulted in more inclusive structures. Today, when new life wants to move into an old house, a very interesting relationship between the old and the new develops, which is usually beneficial to both. In addition, there is an incredible amount of unused space in the city! Why couldn’t we use what is already here for several functions simultaneously?

Can an architect really play a key role in replying to this question?

As a matter of fact, decisions on function unfortunately are eventually made without architects. This is demonstrated by the current examples of the Liget and The Castle. There’s no forward planning, although if you have a building constructed as a client, you should be able to anticipate what’s likely to happen at least ten to fifteen years into the future. Based on this, we can ask whether we really need a new building to fulfil a particular function. Next to this, stylistic and formal issues pale in comparison. Although architects talk about these problems, it is as if decision-making and professional discourse ran on two separate planes.

A few years ago, you said in an interview that “since the change of regime, no culture of critical discourse has emerged, and we don’t have the language for it.” What do you think could promote the development of such a culture? What is missing?

First, architects do not dare express real criticism, and secondly, they may be restricted by the need to step out of narrow architectural thinking. As long as we were talking about style periods, it seemed quite clear what the criteria of a particular style were and what it meant to make a mistake in that context. With no canon today, the critical basis itself is also fragile. If we asked two people to give a review of what has happened in Hungarian architecture in the past twenty years, I am sure that there would be hardly any overlaps between the two reviews. There are no criteria for risking making a judgement, even if, on the whole, everyone knows which buildings are really good. Interest and identity also permeate critical culture, but criticism, if honest and in-depth, could be useful. Everyone says, of course, “But it was honest criticism,” and then there’s not much you can do with that.

In relation to this issue, you have also launched the Ethical Architecture Prize, which is awarded every year for a thesis.

Ethics can be scaled and measured in a building, because the ethical aspect includes uselessness, overspending, future proofness, usability; so there are categories that are objective. Unfortunately, ethics also covers the function that a house serves. For example, constructing a building for homeless people is obviously an ethical act in terms of function, but may still be unethical in terms of architecture. So the functional content of the building cannot be considered separately from this issue, and this is largely not subject to the decision of the architect. The most they can do is decide what jobs to accept or not accept. Peter cancelled two large jobs, resulting in huge financial losses, because he could not come to an agreement with the client. Such things happen too.

What kind of jobs would you refuse to take?

It’s quite clear… I wouldn’t agree to design a shopping centre, a football stadium, a conference hall… I wouldn’t take any job that I think would mean destroying a part of the city according to my own set of values. Currently, the most striking example of this is the reconstruction of the aristocratic palaces in the Castle, all of which, unfortunately, have architects. Back to the prize: ethics is a valid aspect even at the level of the students’ works. You can see it in the diploma thesis subject that a student picks. There is some unfairness to this, of course, because not everyone in a given year can choose the same subject, but the primary purpose of the prize is not to distinguish them but rather to remind young people that there is something called conscience, which is closely related to ethics.

This reminds me of a line that Peter Reimholz quoted at the award ceremony: “I cherish a precious continuity.”

The sense of continuity is indeed closely linked to ethics, and for me it also implies a commitment. It’s not about the need to design old-fashioned houses – neither Peter nor I mean forms. Continuity means that one relates the necessary change to the past and tries to establish some kind of relationship with it. Continuity may also manifest in one’s behaviour or even in one’s linguistic consistency. Today, we are less and less able to talk about the point – something in which the violent progress of visuality probably also plays a role. We have difficulty focus on something for more than a minute or two, and when we see a picture, the text barely registers. I don’t know exactly where this is rooted, or what can be done about it, but I do know for fact that the practice of formulating things is important. The need for formulation is like a mirror. This is the reason why I also miss critical discourse.

Do you have an aversion to star architecture because of its lack of continuity?

In many cases, continuity and interdependence lend authenticity to the new. With the emergence of star architecture, a lot of light, flighty buildings have sprouted up in cities, and computer programs have given architects tools for design and easy self-expression that serve as a kind of personal self-fulfilment. The star buildings are usually the big hits of international corporations or rich people… the products of a type of competition spanning borders and is not intended to focus on architectural quality but rather on grandness. I think that this intention is not in line with the basic truth of architecture, which implies that what we need to create for people is space. From this perspective, star architecture is more like object design. I have no doubt at all about the satisfaction an architect may feel when conceiving of a bolt course at a height of fifty metres – something they decide to call a tower block – that is eventually realised. But the money and effort that goes into the product is not in proportion to the outcome… as if all that was misplaced, and it was not what this world needed.

Do you have a project that has not been built, no matter how badly you wanted it to?

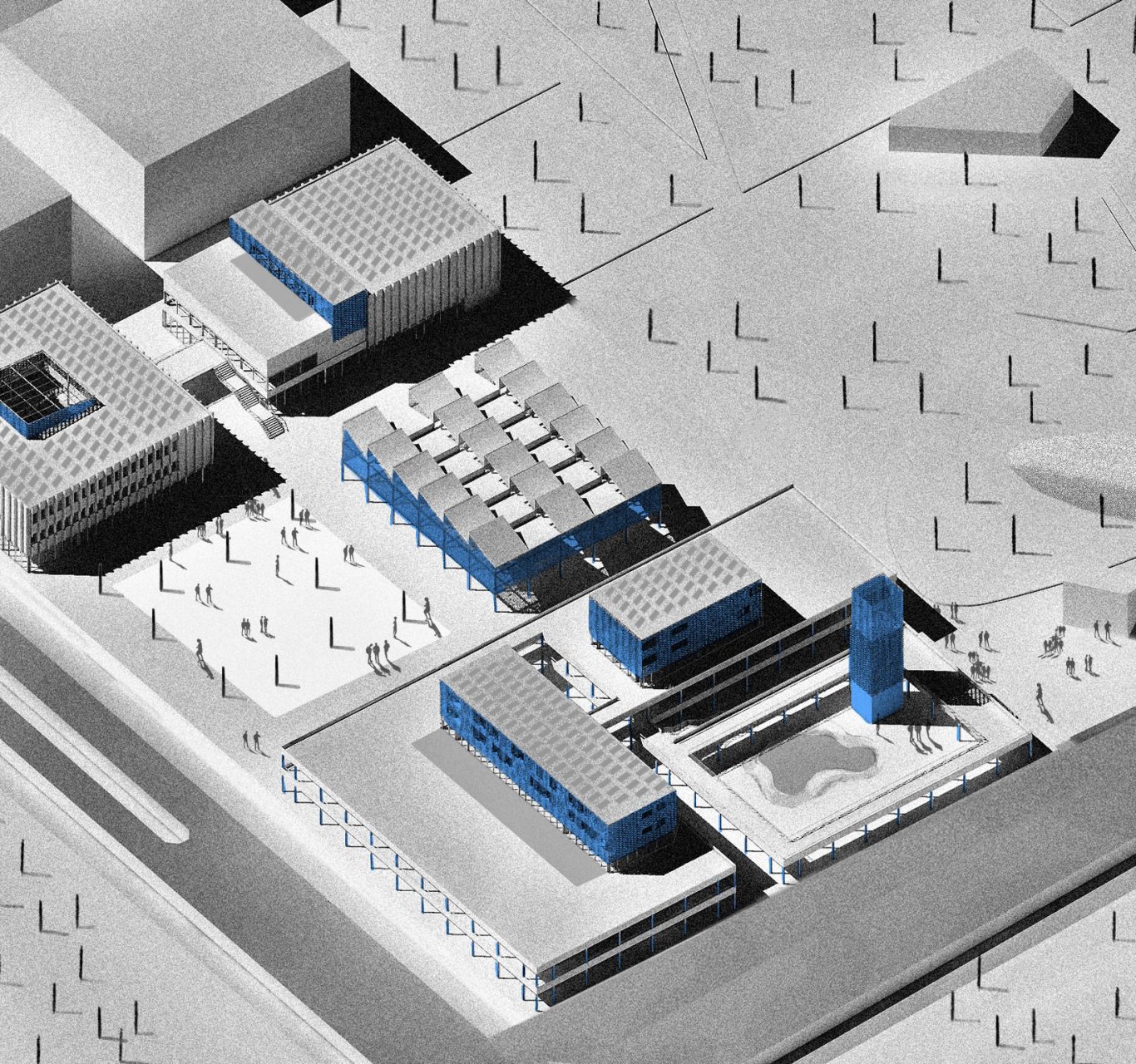

There are a few that I feel sorry for. György Nagy and I designed a studio building on an absolutely nondescript corner plot in Reitter Ferenc Street. It would have provided a space for ceramists, goldsmiths, graphic artists and painters, with a community space downstairs. It progressed the implementation plan stage, but money eventually ran out; I feel very sad about that, it was a good plan. As I have been arranging Peter’s legacy recently, I have come to realise that perhaps only a tenth of the plans have been actually realised. Block reconstruction, urban planning, whole city districts – it’s incredible how many things have come to a halt.

You said earlier that you would enjoy being a twenty-year-old now. What is attractive about today?

I have never wanted to be younger; age doesn’t bother me and I have been blessed with good health all my life. But now, our profession is changing at a pace that makes me curious. An architect can land themselves in a situation covering a much broader spectrum, which does not mean that they become a more prominent player, on the contrary: they can function as a ‘public figure’. If many people start dealing with one thing, it will have a much bigger impact than if only one person designs a building – a collaboration of professions is what is needed. The future today is uncertain in very many ways, but has to be good!

// /

* Péter Reimholz Ybl- and Kossuth Prize-winning architect, university professor. He passed away in 2009. He received the Moholy-Nagy Award posthumously in recognition of his work.

Author: Ákos Schneider