The relationship between object and tradition – Eszter Kain’s ‘St. Lucy’s chair’ handbag

A large part of Eszter Kain’s works is centred around the reinterpretation of traditions and traditional forms. Her earlier research focused on the act of mending items, moribund professions related to mending, and the importance of appreciation. Her ‘St. Lucy’s chair’ project highlights several intriguing correlations in this regard. The burning of St. Lucy’s chair forms part of the traditions surrounding St. Lucy’s Day. The appearance and functionality of the three-module handbag reflects on the same tradition.

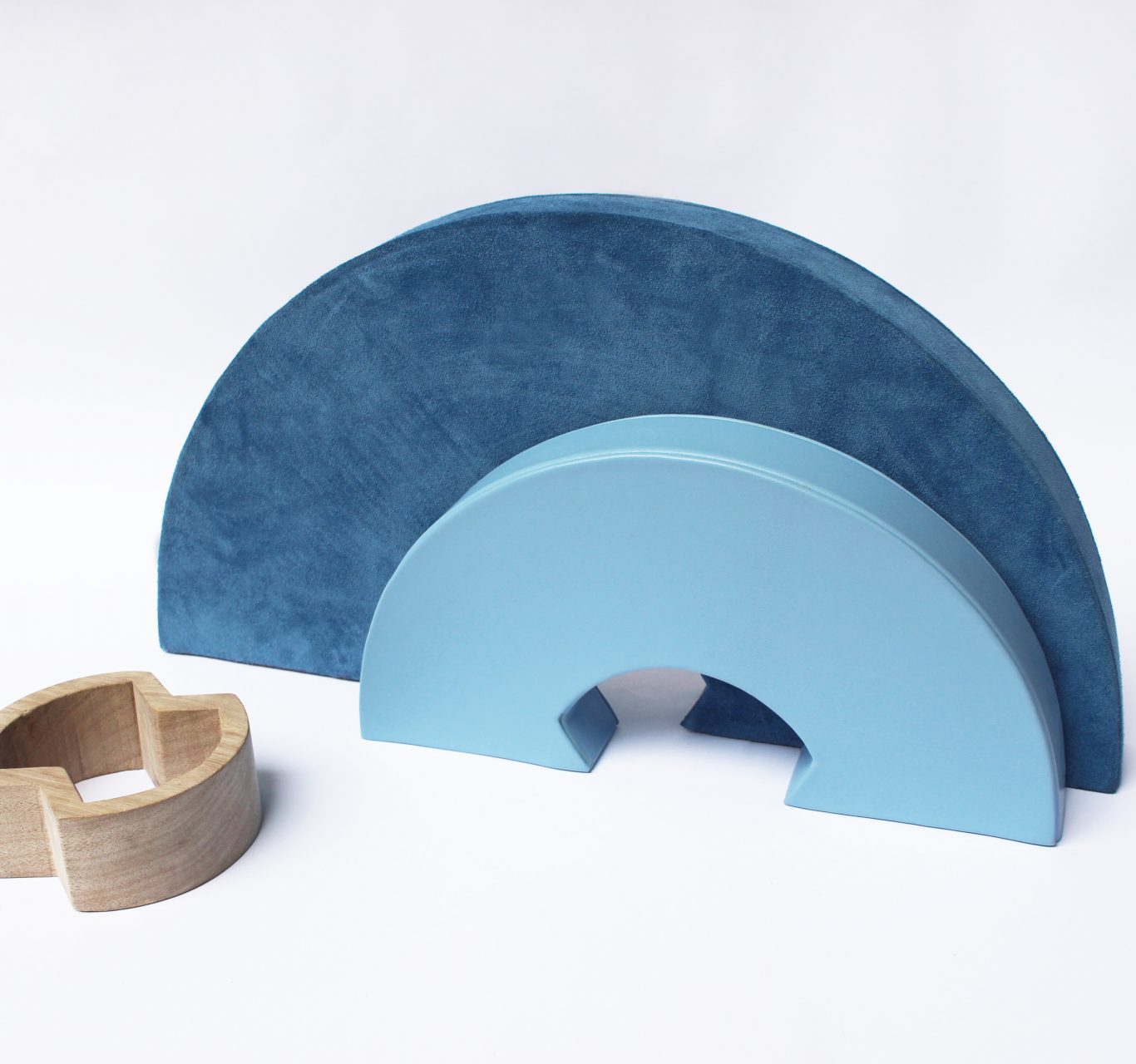

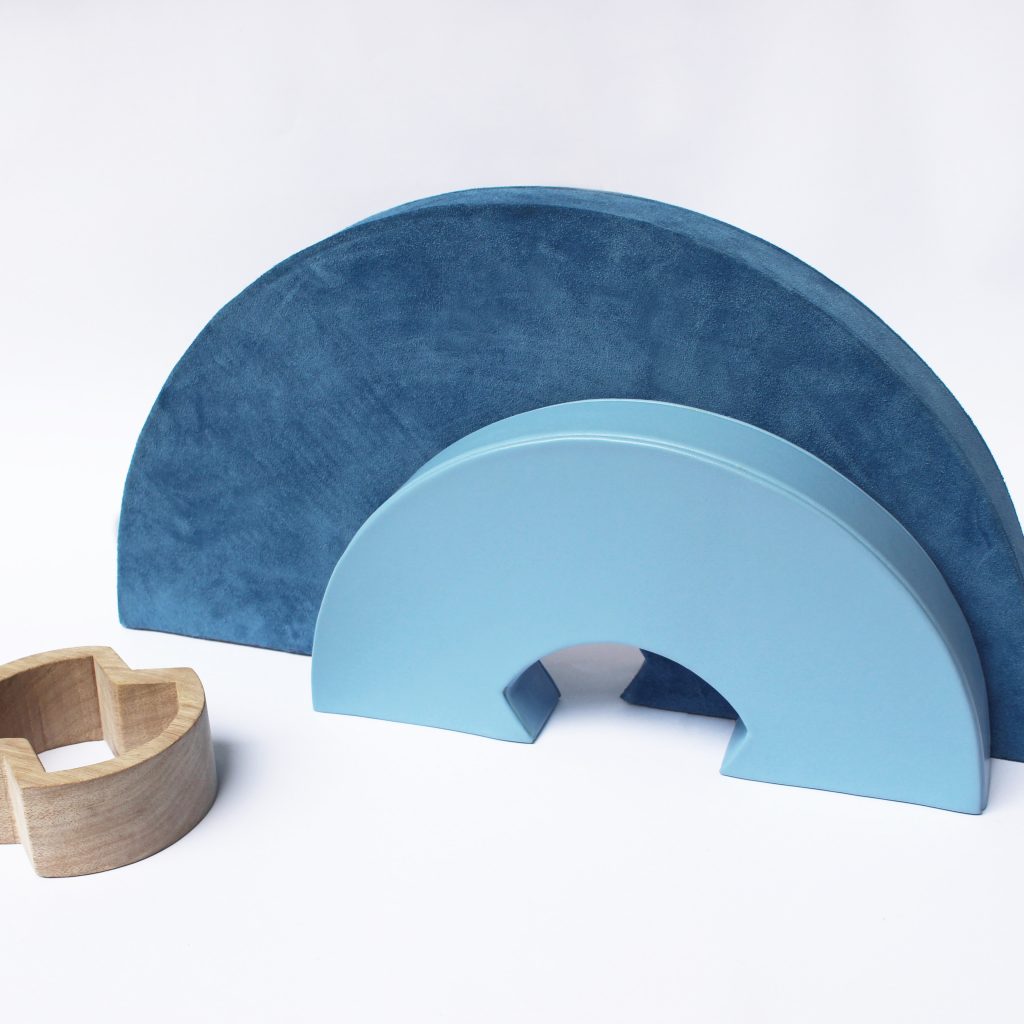

The item has a structurally transparent, clean design. It was made from wood and leather, using different application techniques. The “body” is composed of a larger and a smaller module, both of which come with the same wooden handle. The components can be easily disassembled and reassembled, reinforcing the motif of multiple uses. Each time the handle is attached to the other bag, the item is kept in a sort of circulation. The two bags can also be fitted together using the wooden element, creating a pleasant contrast between the leather and suede textures. The juxtaposition resulting from the use of various materials is also part of the tradition:

“St. Lucy’s chair is made from different types of wood, which is why I also used a variety of materials. My bags are designed so that they can be assembled from different pieces using wedges and can be disassembled.”

The combination of the three modules has a playful quality. Their shape and the way they fit together are also a reflection on the toy blocks inspiring her earlier bag collection.

The semicircular module of the ‘St. Lucy’s chair” hides a hollow compartment that can be pushed open from both sides. When pushed from one end, the inside compartment emerges on the other end, and can even be pushed back into the opening on the opposite end of the semicirclular module. The motif of circularity and circulation is once again come into play as a result of the functional qualities of the shape. It is a reference to the tradition of mending, as in the old days, when every item had a specific way of mending it, the useful life of our clothes and utensils could be considerably extended. Each repair symbolises the completion of a full cycle and the beginning of a new one.

It is easy to spot that both the materials and the design are fixed and inflexible. As a clothing accessory, it is not flexible because of its shape, and it does not conform to the human body because of its material. The question arises why the designer chose to present her work as an accessory rather than a home decoration item, say a storage box. The answer may perhaps lies in the tradition of the burning of St’ Lucy’s chair’. St. Lucy’s chair is made to be burned afterwards. It is hard to say whether a chair crafted to be destroyed can fulfil its original purpose. Can it support weight? Can it stand upright? It does not matter – it is going to be fed to the fire after all. This way, St. Lucy’s chair is not really a chair. The same is true for the handbag: is it really a handbag if it only looks like a handbag, but once in use can only serve a limited purpose?

‘St. Lucy’s chair’ is a great metaphor for today’s consumer culture: items are produced to be used up and discarded within a short period of time. Since everything can be readily repurchased, trying to mend things is simply not worth the hassle. The designer succeeded in exploring the subject along an excellent analogy and raising awareness around moribund professions related to mending.

// /

The ‘St. Lucy’s chair” handbag collection was created at the Textile Design BA of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in 2020. Consultant: Ildikó Kele

Photo by Doro Novák