“There’s no need to build a lot, just use what we already have”

Though rural development, Ábel Laki’s topic of choice, has become quite the rage lately, his diploma project is completely void of any trace of trendiness. We would be hard-pressed to find grandiose building complexes, houses subtly blending into the rural landscape, or extensive infrastructural interventions in it. He not only approached his subject with a great deal of social sensitivity and pragmatic prudence but has entirely dedicated himself – now as a freshly graduated artist – to a real-life architectural situation. He won the Rector’s Award for his masterwork Revitalisation of Railway Line 78, and we chose this occasion to ask him about the rural areas versus the city, opportunities and issues, plans and anxieties.

According to the project description, the starting point of your masterwork was the disparity between rural and urban areas. How did you happen to stumble upon this undoubtedly relevant topic?

The countryside has become a fairly hot topic in recent years, it’s practically inescapable. However, the definition of ‘rural areas’ is not at all obvious, no matter how simple it may sound at first. On top of that, the whole subject is sugar coated in the aesthetic sense, which does not help rational discussion – quite the opposite. The problem with the aesthetic approach is that it looks at rural areas from the perspective of city people, and strongly romanticises situations in life that are less than optimal. What I’m trying to get at is that that discourse plays a crucial role here, at the same time, discourse is initiated by city people, which automatically creates in a hierarchical relationship. The starting point of my masterwork is the realisation that we are all interconnected in a complex system – there is no just city and just countryside. Both are defined in relation to each other, and many problems could be addressed by having some more spotlight on power inequalities.

You have also specified in relation to your masterwork that having access to necessary services is a basic human right, but everyday reality is not at all so rosy.

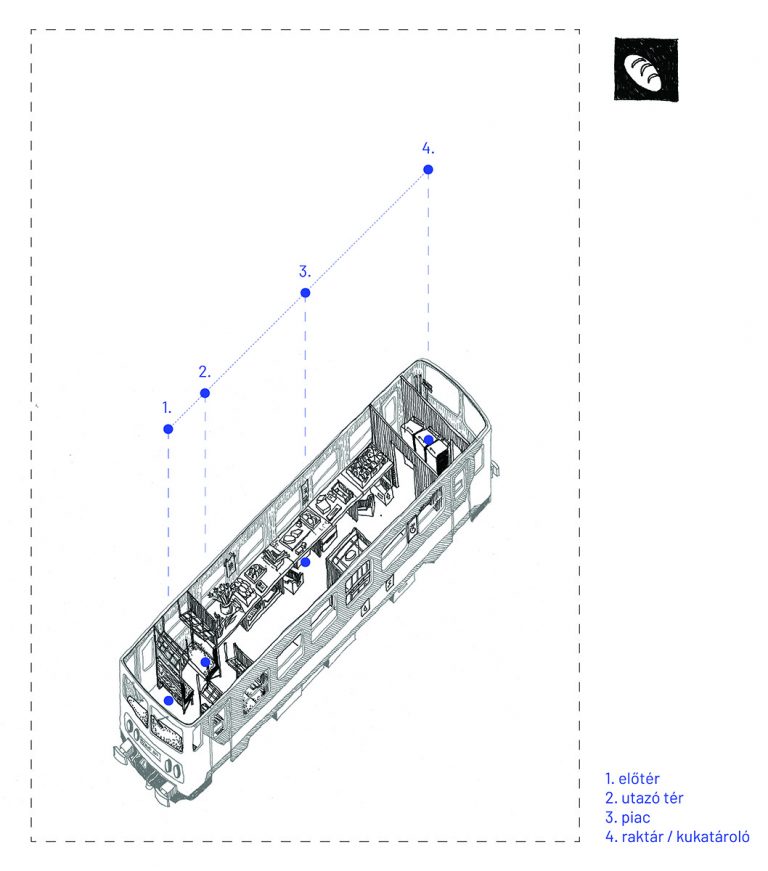

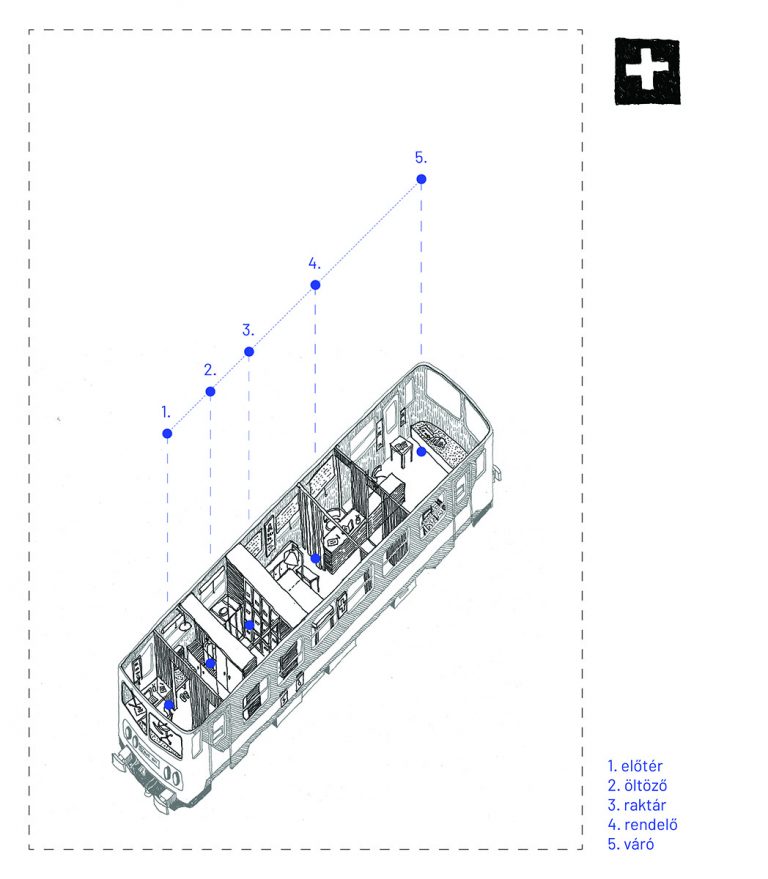

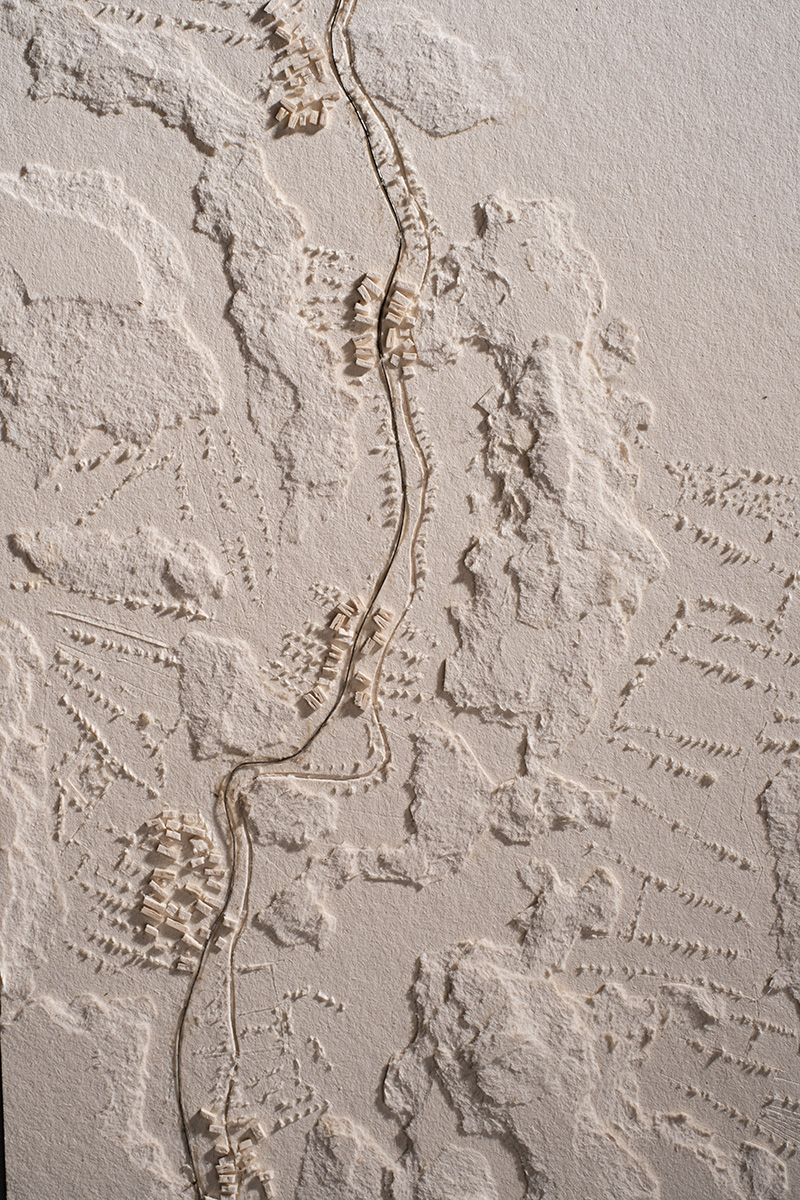

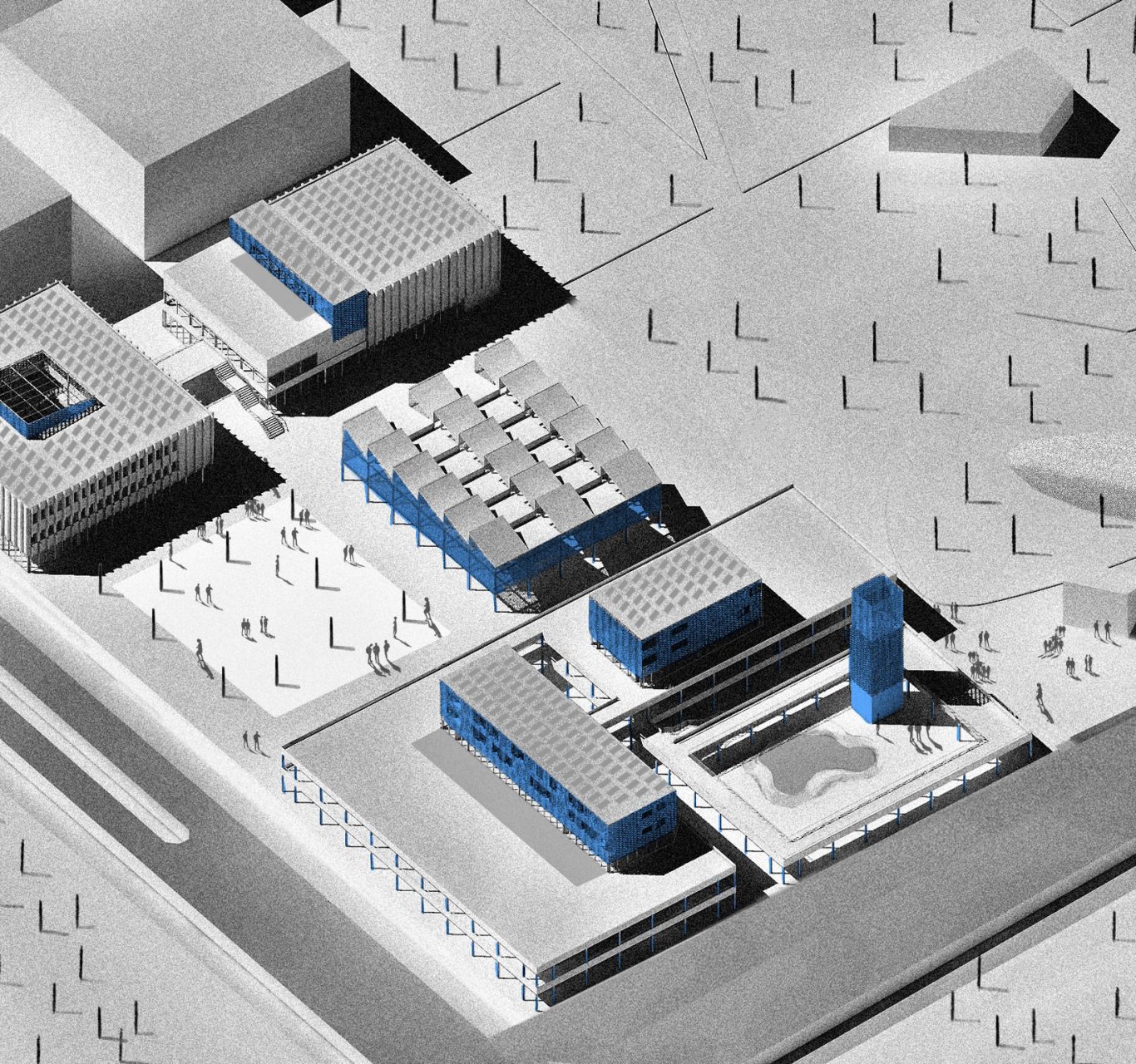

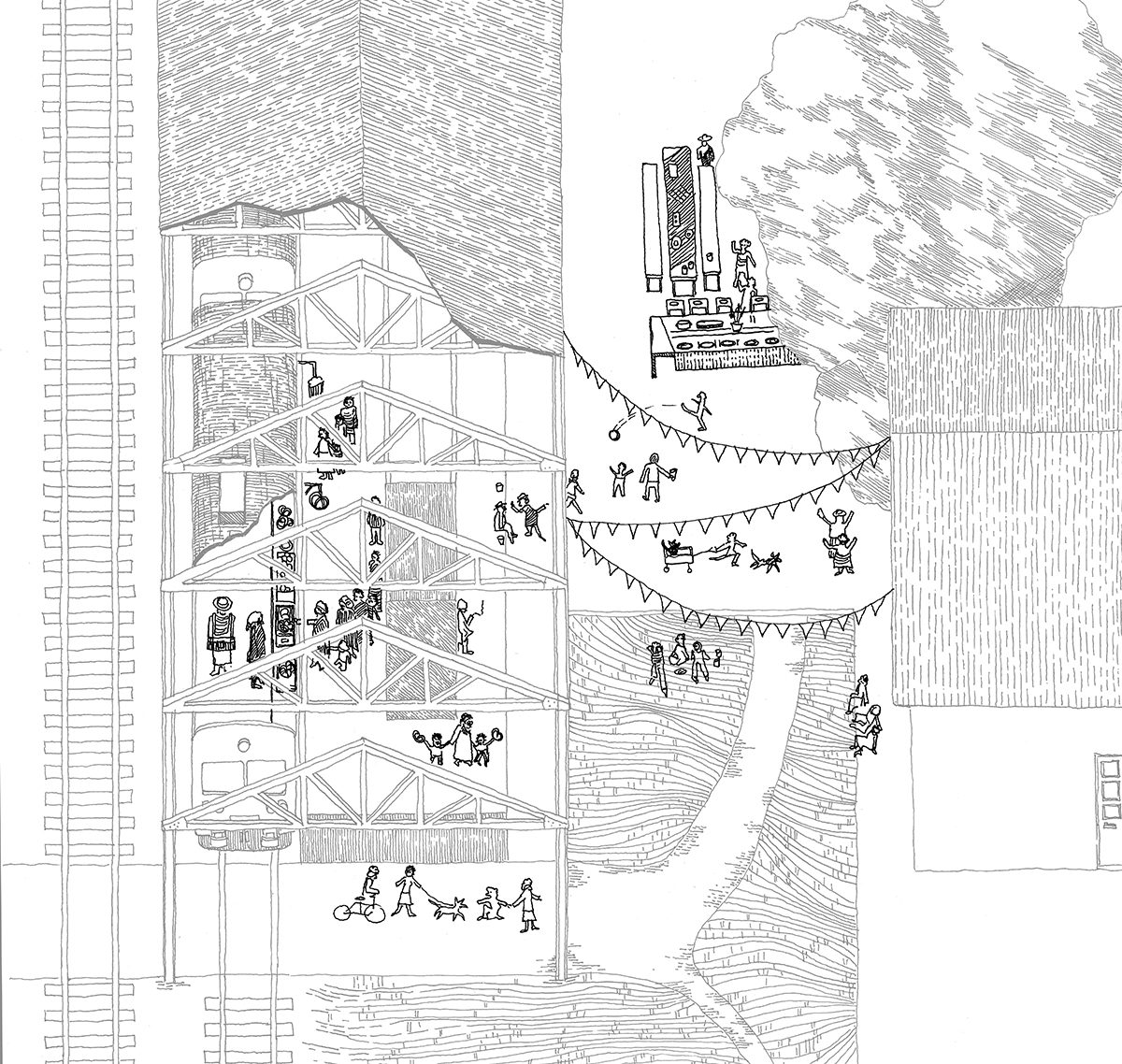

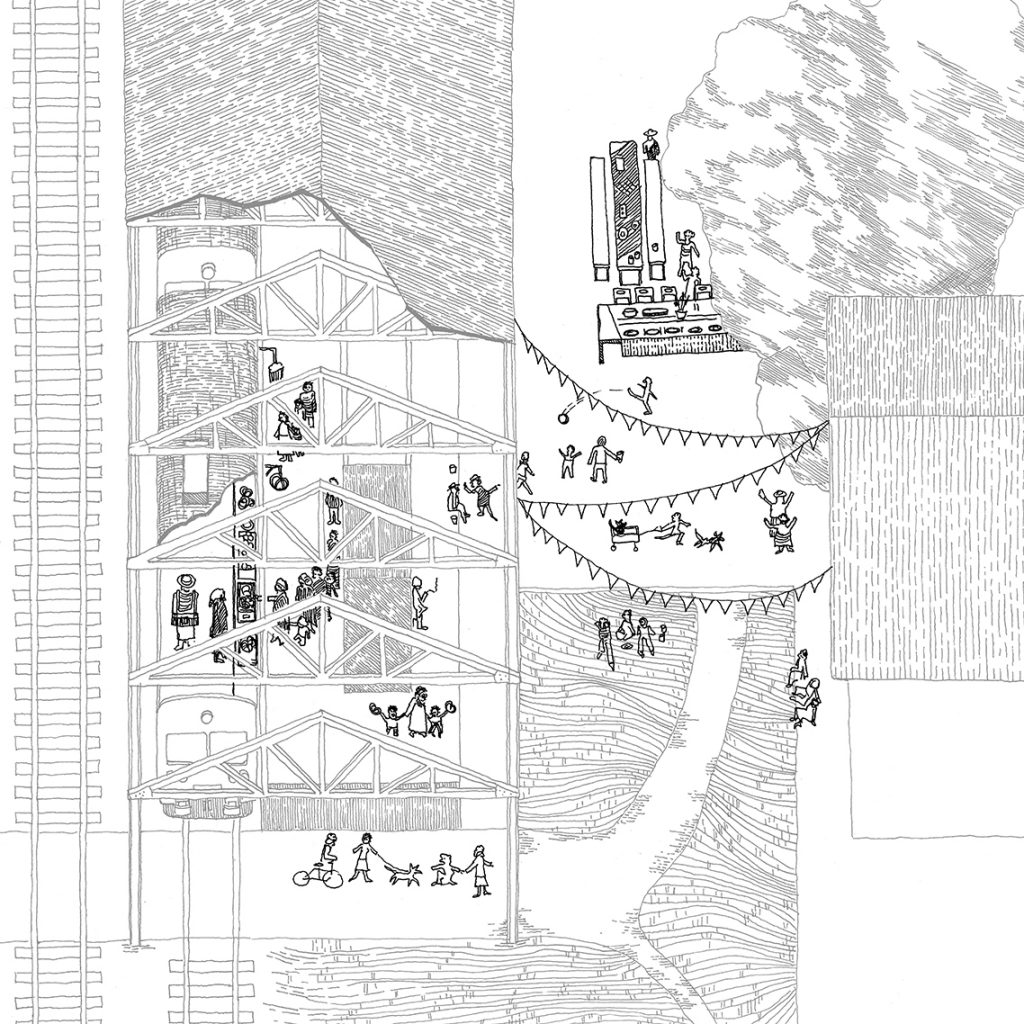

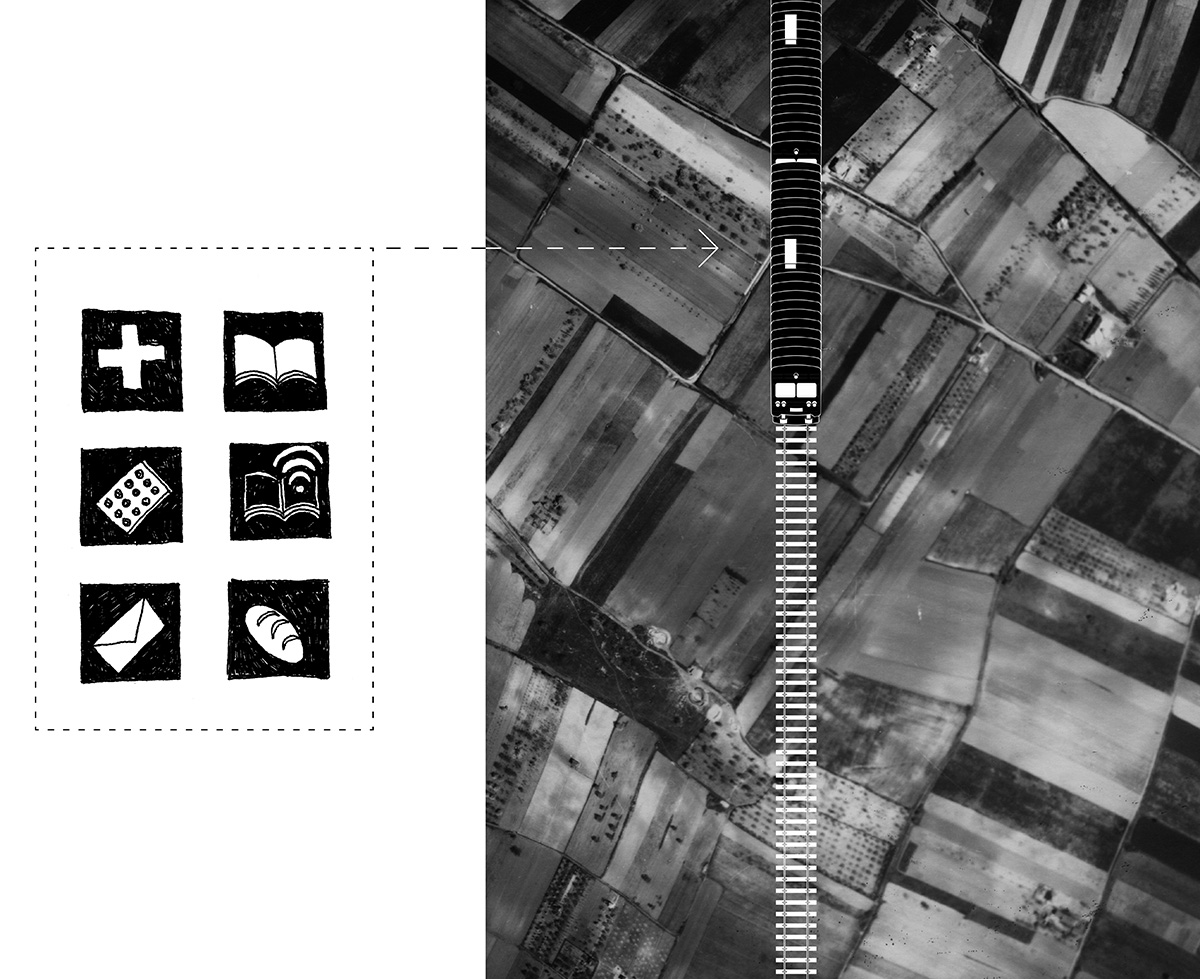

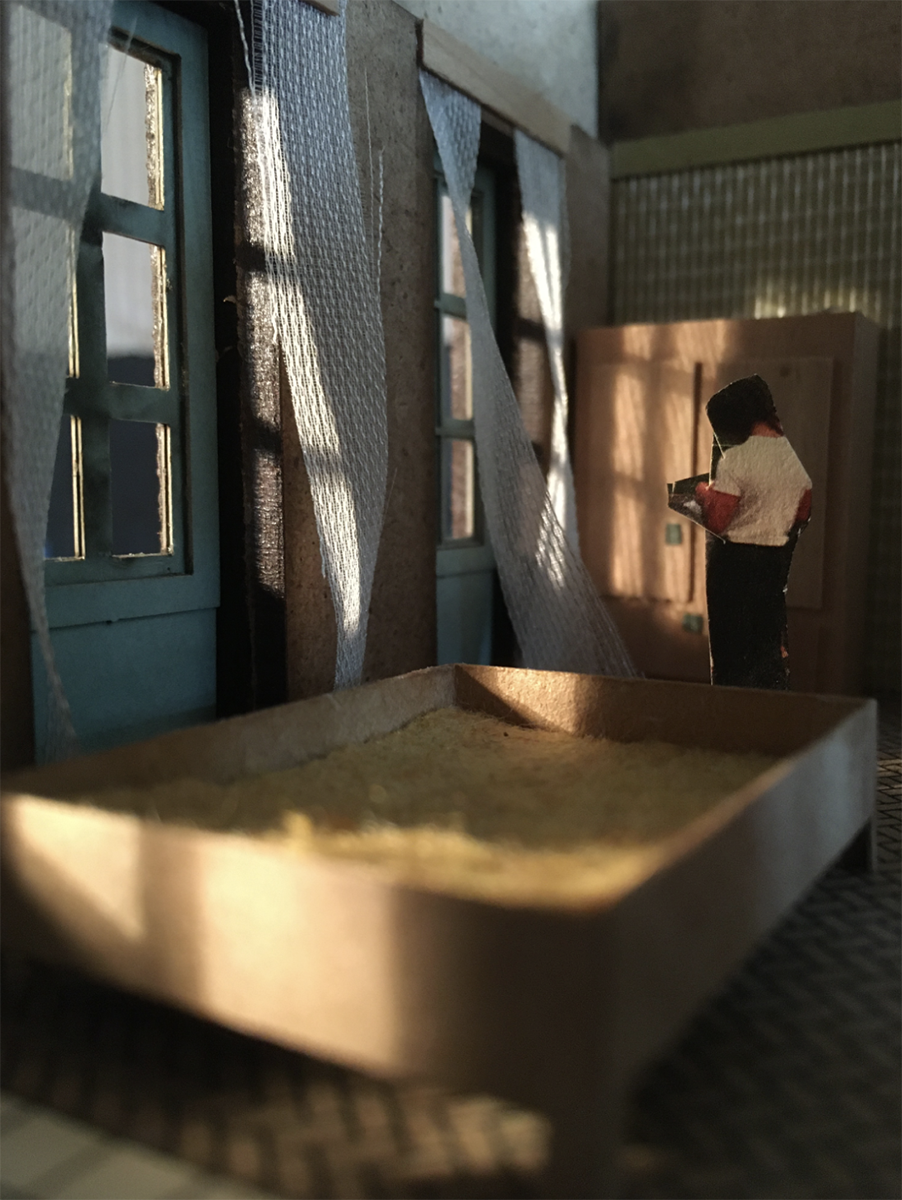

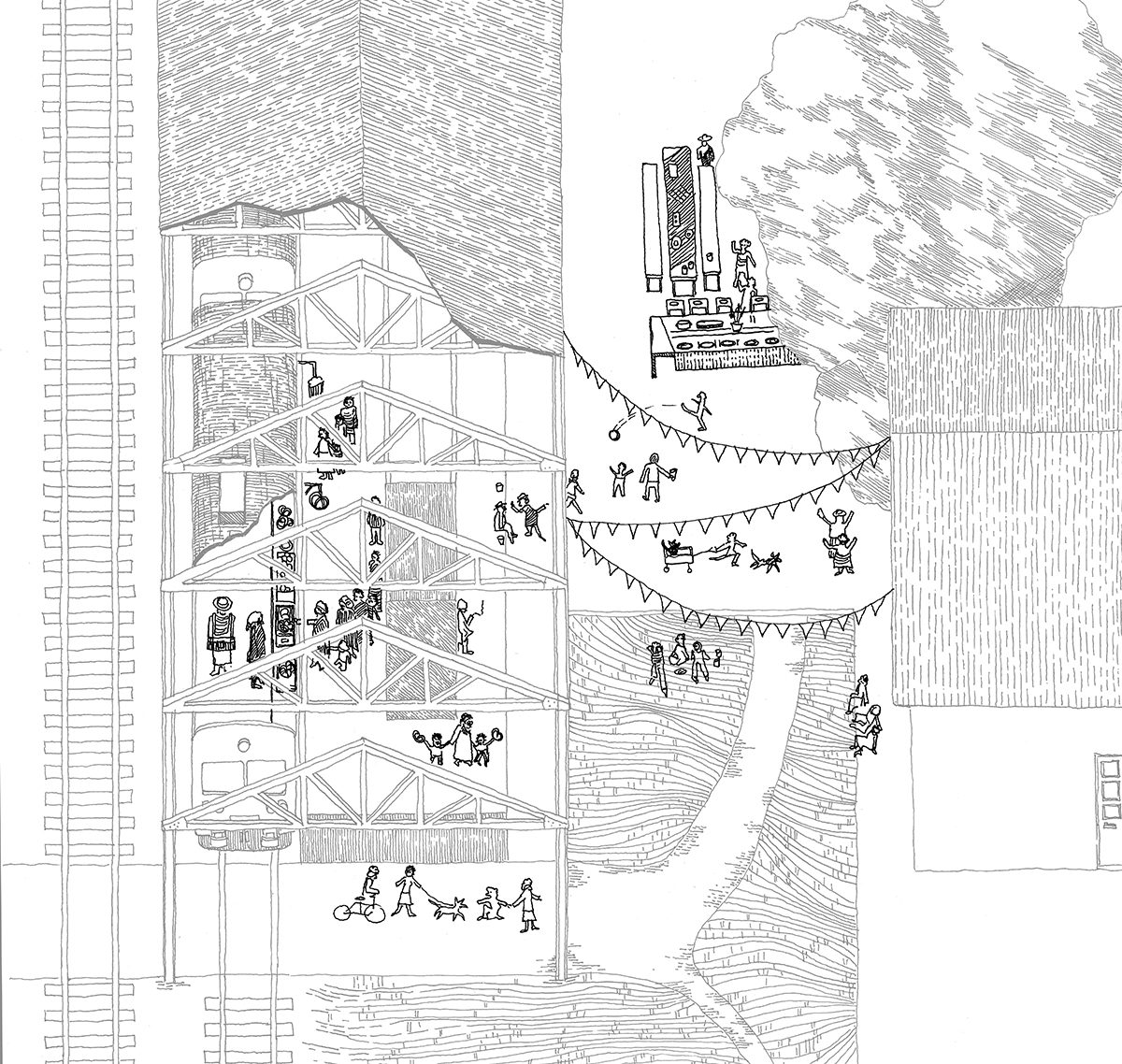

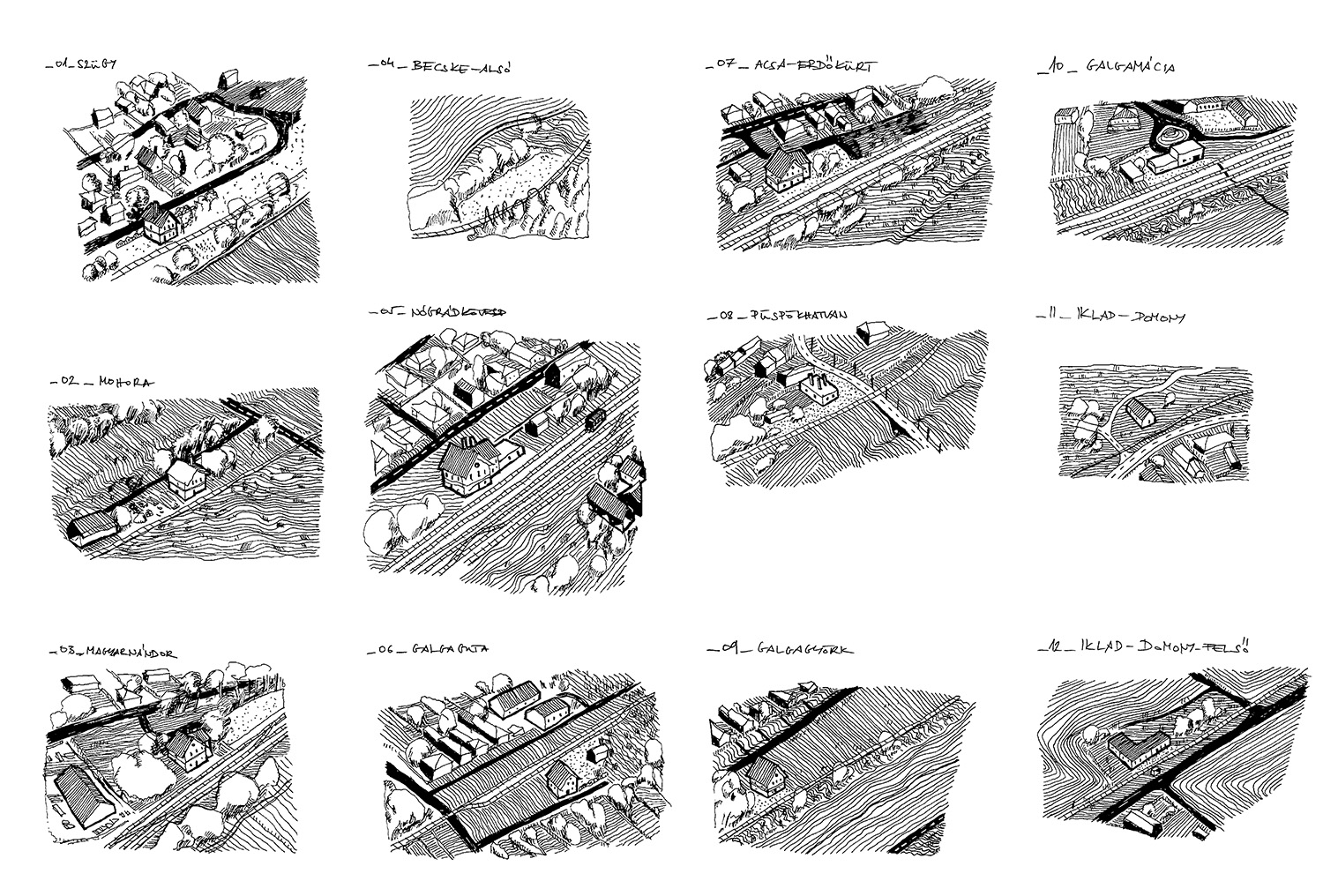

Who has power over deciding about subsidies, who can identify the forming elements of rural life, or who can dispose over components of infrastructure all have a direct impact on tangible issues such as the lack of sufficient basic services such as school, kindergarten, postal service, grocery store, pharmacy, medical service in rural villages and towns. I believe that these deficiencies are the hallmarks of disparity. If we accept this realisation as true, the need for network thinking logically follows from this, and making ad-hoc interventions here and there would be ridiculous. In my case, the infrastructure of the railway lines forms the physical basis for the network is. Many of these lines have been out of service, but even the ones that are still operational are destined to be closed in 5-10 years, even though having towns connected by tracks is a tremendous resource. I was simply looking at how to transform these lines to be able to incorporate the missing services. It was the same as redesigning an empty house, only this time I needed to work with tracks, wagons, and station buildings.

How did you identify those essential services? It’s not at all self-evident.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to work alone, I was working with three good friends (and classmates) of mine, Imola Fazakas, Juli Gunther and Szilárd Suba-Faluvégi from the time of writing my thesis. As all four of us were focusing on architectural borderline situations but network thinking seemed too big to take on for just one of us, the logical conclusion was that we can only produce a credible outcome working in a team. In practice it meant having frequent consultations, trying to explore shared issues, and addressing them together. To identify the required functions, I conducted local interviews, trying to locate interview subjects from as many villages and towns of line 78 (Aszód-Balassagyarmat) as possible, including a station master, a dean, a photographer, and a mayor. Naturally, line 78 is just a representation of a network system, and another line might have come with completely different requirements.

Theoretically, the concept could grow into a systemic programme, but, as you also pointed out, the requirements could change from town to town. In addition to unused railway lines, what other objects could be considered?

What I proposed would, in itself, certainly not be sufficient to bring about any major change. Architects have limited tools, and it’s never a good idea for them to overreach. One of the greatest lessons teamwork has taught us was precisely that no matter how different our individual projects were, the basic problems we came up against were extremely similar. Szilárd was focusing on flood zone rehabilitation, Juli on urban food supply and self-sufficiency, and Imola on the building stock of abandoned barracks. Unless we worked together, none of our individual diploma projects would have probably turned out to be credible. With a project like this, many similar programmes would need to be implemented at the same time to achieve some sort of result.

Your thesis was also closely related to this project and focused on rural development possibilities. In your professional opinion as an architect, what are the most pressing problems?

Overall, perhaps the lack of proper perspective. Even the term ‘rural development’ suggests that most people tend to think of the countryside as lagging behind and relying on help from the city. It would be nice to stop viewing the countryside as needing help, because this type of paternalistic mindset perpetuates the power dominance of the city. We should simply start exploring the potential of the countryside. What infrastructure is there in place? What buildings? What human resources? What natural resources, and how could they be utilised to prevent the countryside from needing outside help? It would be possible to get a lot out of local resources even with simple means.

In this vein, you designed a solution rather than a house or building complex for maximum adjustment to the circumstances. What ideas do you have for the future, and how can you take this approach further?

If we inventoried our building stock, we’d probably find there was no need to build a lot, just use what we already have. What I see is that my own generation is affected by a strong anxiety about the future. With our diploma projects, we attempted to alleviate this anxiety by giving our various suggestions a visual representation. Our age group is receptive to experimentation, given that what we have right now is less than optimal. At the same time, I’m also optimistic about finding other people to work with who share a similar approach.

// /

The masterwork was completed at the Architecture MA of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, with Marián Balázs as consultant.