“It’s about redefining my relationship with fashion” – Interview with Valentin Szarvas

Sustainability seems to be everywhere, all the time, and in so many different forms, making it feel like somewhat of a cliché. But our work with sustainability is far from over, something the younger generation of fashion designers agrees with. But as industry insiders, what’s new to say? How can we invite people to think together? Perhaps personal doubts, inner tensions and putting the insatiable desire for authenticity into words can help us see the stakes from a more human perspective. This is precisely what Valentin Szarvas sought to achieve in his diploma project, which received the Rector’s Award of Distinction. We asked him about it.

Your projects feel like a comprehensive, deep dive into various social issues. Your master’s project is a fashion collection entitled “Folding Back on Myself” in which you contemplate sustainability while turning your signature sharp, critical eye inwards. What brought you to such introspection in your designs?

I’ve been interested in sustainability for a while, but in my previous works I only ever really scratched the surface. As part of the design task in one of the semesters, we had various experts come in to talk about their views on sustainability. I think we all know that being able to draw positive conclusions from presentations like this is very rare. It touched me really deeply, and I was angry for most of the semester because of it. I was mad. I was seething. And during this period I was dealing with some really complex inner struggles. I started questioning the relevance of the field I so passionately wanted to be a part of. My thesis advisors, Judit Bárda, Ildikó Kele and Dóra Tomcsányi, helped me understand that the reason I immerse myself in certain topics is because I’m trying to find a way to ease the powerlessness I feel about them. So for me, the semester that just finished was all about experimenting and redefining my relationship with fashion. I should add that I don’t see the final collection, or to be more precise the individual pieces themselves, as particularly good. But they certainly played an important part in helping me look inward as a designer.

We are talking about introspection, but it’s a long way from being self-serving, because your reflections are part of the circularity that defines contemporary fashion and economic theories. How did this profoundly personal aspect merge with global problems in the various phases of the research and design process?

The goal of reflecting on myself was to find harmony in the themes of my previous collections. I found several constants, but even the variables surrounding them had a kind of interdependence that meant they built upon one another. I saw how my identity as a designer moves in a circular system, starting out from a very similar central point and trying to find itself in the present. In essence, I tried to define myself in the system of contemporary fashion and the corresponding economic theories. I worked to define this presence by examining the topics that flow through me as a subject.

Your works often seem to be inspired by other art and artists. In the spirit of continuous change and renewal, what pieces have inspired you this time round?

Visual art in all its form has always had a great influence on me. When I recognised the circularity I mentioned before, it immediately reminded me of a painting by Judit Reigl called Centre de Dominance. I watch a lot of interviews in my free time, which is how I came across this painting many years ago. It had a huge impact on me, but for a long time I didn’t know why. In the interview, Reigl said that her gestures depict the present, or the presence of the painter in the moment. It’s a visual representation of a process, in which, although the picture is still, the constant is always changing. In paintings these gestures can cross over each other, collide and break each other, which can bring their shared origin to the surface. These thoughts also led me to the work of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson believes that finding ourselves happens in parallel with exploring the world around us: we influence the external world while it shapes us at the same time. It is important to find the balance between our internal world, and the world around us, as the two together form a whole. Cartier-Bresson wanted to capture that defining moment when everything comes together: we feel what has happened before and what is about to unfold. In fact, it’s more than a feeling. We know. It embodies an in-between state, the present that is bound to pass. This is when I discovered Mexican multidisciplinary artist Jose Dávila, whose installations are pregnant with the possibility of change through their tension with space.

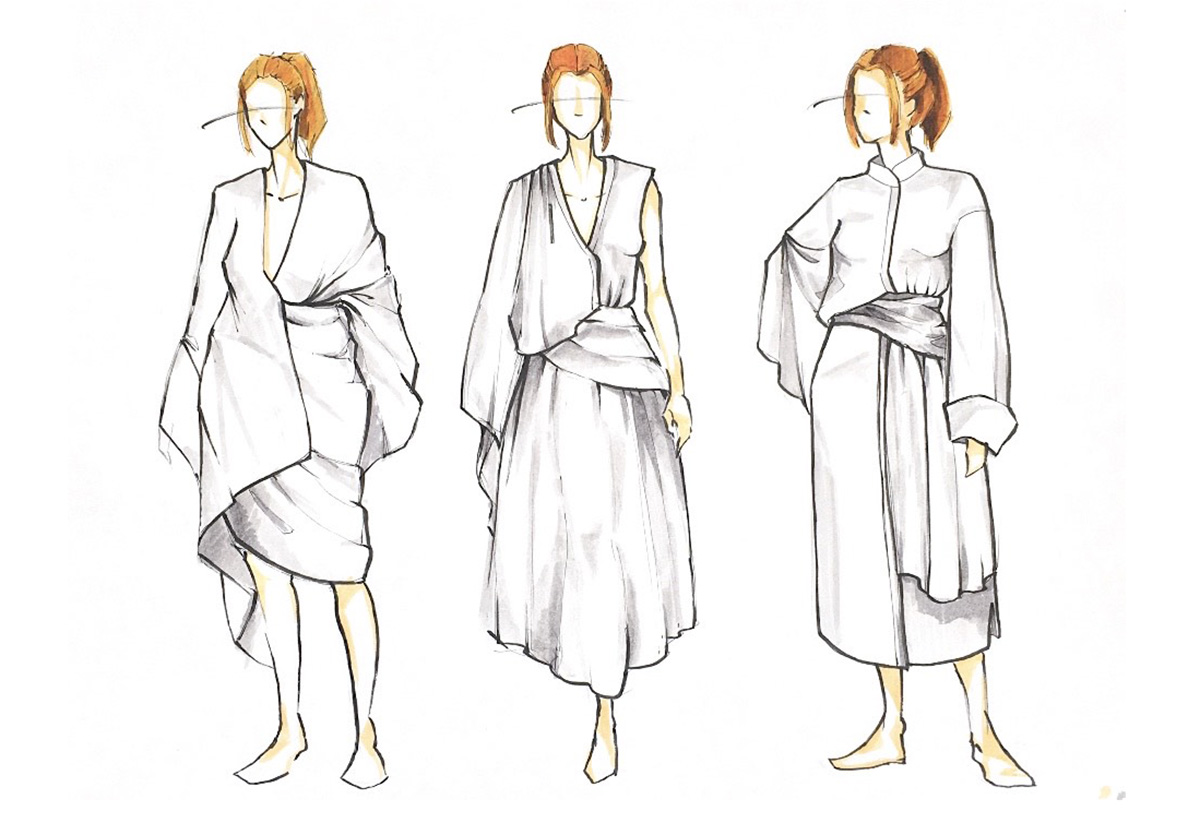

Instead of using busy, almost kitschy patterns that were a recurrent element of your previous collections, it feels like this time, your focus shifted more to experimental shapes and the structures of the garments themselves. What made you change your focus? Why did you decide to turn away from vivid patterns?

There are a number of reasons, but the most important seems to be that in the final stage of mass production kitsch is created unconsciously. By that time, quality is trumped by quantity and the need to make items quickly, and patterns take away the essence of the structure. In response to this, in my master’s thesis collection, I strove to experiment with form, which, I believe, shows how my approach to design has become deeper and more nuanced. Of course, it doesn’t mean that I have turned away from consciously generated kitsch. I just don’t feel it’s relevant either in my environment or in fashion at the present moment.

You documented your experimentation with different shapes during your project, and you used the footage to create sequences of images. What role did video and photography play in your design process?

This step is connected to the ideas of Cartier-Bresson I mentioned earlier. Fashion seeks answers in the present moment: like many other things, fashion is about examining ourselves and our sociocultural environment, discovering the world that surrounds us and finding the links between these things. As a product or art form it draws the lines of transition between the distant past and the distant future. I wrote a few sentences outlining my thoughts on my artistic inspirations, and I tried to find visual synonyms for these thoughts in my experimentation with shapes. The videos I made helped me incorporate the nature of the movement I had captured into the finished garments. I cut still images from the videos to look for the most characteristic, most defining attributes of the silhouettes. From a freeze frame of a garment, the form it took in the past and how it will move in the future crystallise. Essentially, we see the in-between moment that precedes its final stage.

Thinking in sequences is also a part of the inner logic of the collection, as you created the garments in three stages: you clearly separated the embellishment, construction, and placement of individual components. How did you come up with these three phases and what do they mean exactly?

Let me summarise what we’ve been talking about a bit, then I think I can answer that question. Sustainability is not an individual concept, but a process that can be pursued endlessly. The basis of circularity is constant change, and the basis of change is the existence of a constant entity that undergoes the process and can revise some of its basic tenets, while always seeking to return to its original state. In my master’s project, I have defined the phases of these changes within the system garments are found in. By defining the various phases items of clothing go through, I have developed a unique system, which I have presented through the collection that constitutes my master’s project. The first phase was all about decorating the garments: I built this stage around sewing techniques and symbols that can flourish further once they become part of the garment. The decorative threads I used last longer than the natural material the garments are made of, so they outlive the textile as it breaks down, thus creating change. During the second phase, I stepped away from the surface of the garments and examined their construction, and how the silhouettes changed. In the third step, I dealt with the predefined placement of the individual components. For this, I used black double-faced fabric the two sides of which are created by matching two identical materials. I put the garments together with double-faced hand stitching, meaning that I divided the merged fabric along the seams and cut lines, and then I sewed them together once again so that the cut edges could run along the structural lines and between the two layers of fabric. I made the hems with the same technique so that they end by folding onto themselves.

Two garments feature the symbol of a dog biting its own tail. With its sophisticated minimalism, this pattern feels like a statement. What’s the meaning behind it?

The inspiration for the pattern is an ouroboros, the symbol of eternity, eternal circularity and continuous renewal. In my collection, the pattern of a dog biting its own tail alludes, in part, to circularity, and dogs also often chase their own tails to relieve anxiety. A symbol that brings together circularity and anxiety serves as the visual representation of my attitude towards design, which references the sense of helplessness that defines my identity as a designer, which I explored in my thesis.

// /

Valentin Szarvas’s diploma project “Folding Back on Myself” was created as part of MOME’s Fashion and Textile Design MA programme. His supervisor was Dóra Tomcsányi. Anna Keszeg contributed as thesis consultant and Judit Benczik as technology consultant.