“We still don’t feel ownership for public spaces” – Brigitta Ádi’s art tour

Why do certain sculptures get removed while others are kept? What is the real meaning behind renaming streets and squares and rebuilding areas of historical significance? How much do we know about these processes that go on under our noses, and how public are public spaces in the first place? The concept is hard to grasp, especially without picking sides between left and right. Design theoretician and curator Brigitta Ádi opened the opportunity for meaningful dialogue with a combination of increasingly popular thematic city walks and podcasts. Completedwith the support of the Erika Deák Grant, her project Thinking by listening, listening by seeing helps explore our complex relationship to our public spaces through location-specific artworks.

The project was preceded by in-depth research exploring the relationship between public spaces and their users, and their invisible modus operandi. What personal experiences made this subject so relatable for you?

It struck me that tourists to Berlin adopted the strange habit of pressing their used chewing gums onto the remnants of the Berlin Wall on Potsdamer Platz. It is not an unprecedented trend – in the USA for example, gum walls have become widespread – but in this case this involves an important historical landmark. So I became interested in how humans leave marks, such as what is a single piece of a historically complex and shifting structure is doing in Potsdamer Platz, when and how it was changed, how the square surrounding it was transformed, and why it is visited by tourists at all. I was intrigued by all similar interactions, especially the removal of the chewing gum mass, which has become a real political event, with heritage preservation experts and naturally also politicians showing up to have their photos taken. When doing my research, I came across Ágnes Kapitány and Gábor Kapitány’s paper “Street talk and its relationship to legitimacy” exploring how the components making up a public space – buildings, advertisements, people, smells, sounds, or garbage, for example – all work together and what is their relationship to the current power, whether political or other. That’s when I started working on a project that would help people grasp these oftentimes invisible interrelationships.

Have you by any chance looked into Hungarian examples beyond Potsdamer Place?

No, my research focused on the temporal and spatial segmentation of a specific piece of the Berlin Wall. After these ideas first took shape, I started thinking about how to adapt them to my current environment at the time.

What made you think ephemeral and location-specific artworks would be the right choice for this?

Due to its extension in space and time, a public space cannot really be judged based on a picture, and is perceived more as an imprint left by somatic experiences. Also, when discussing their work included in the walk with Antal Lakner and Pál Gerber, they pointed out that the gallery space is for an isolated community only. For these reasons, I wanted a format that goes beyond the conventional exhibition or museum setting, and help get the project across to the public in the most democratic way possible. Public space-related issues on the other hand are highly complex, which is why specific artworks were required to help us talk about and think around them.

Your project was not only implemented without white cube spaces, but also ties into thematic city walks and podcasts, both of which have gained popularity in recent years.

I’ve reflected a lot on precisely who I want to reach with this project and how. One of my target groups are high schoolers and university students not specifically studying or working in cultural fields. I also wanted to reach out to subcultures that can relate to the subject, even if marginally, and that’s how I came to choose hiking challengers. In order to reach this group, a debut event for the audio play that was the main output of the project was designed and advertised through the calendar used by hiking challengers. Eventually, quite a lot of people showed up, such as hikers with their families, or an older lady from Győr. Since the sound files were uploaded to platforms like Spotify and Sound Cloud, people other than our target groups can come across them.

What other subcultures would you like to reach in the future with your project?

So far I’ve only been able to reach these groups, but I think a lot about what the next step could be. I have contacted several teachers because they could incorporate the materials into the art history syllabus.

The artworks described during the city walk cover the period between the mid-80s to the early 90s. What were your selection criteria?

For me it was important to select ones that are connected to Budapest, because that’s where I currently live and I have the closest ties to. Due to its format, the project can be easily adapted to another city, period, or artwork. When making the selection, an important consideration was also to pick works that can walk us through the regime change. From a legitimacy point of view, there has been no major shift in our relationship to public spaces. In the early 90s, however, it was felt that abnormal situations caused by strict control came to an end. So in the walk, we proceed from György Galántai’s half-clandestine process work from 1985 through Tamás St. Auby’s work to Lakner and Gerber’s artwork created as part of the official Polyphony event series of 1993.

You mentioned hiking challengers as an important target audience. For the selection of the artworks, how important was the route that they traced?

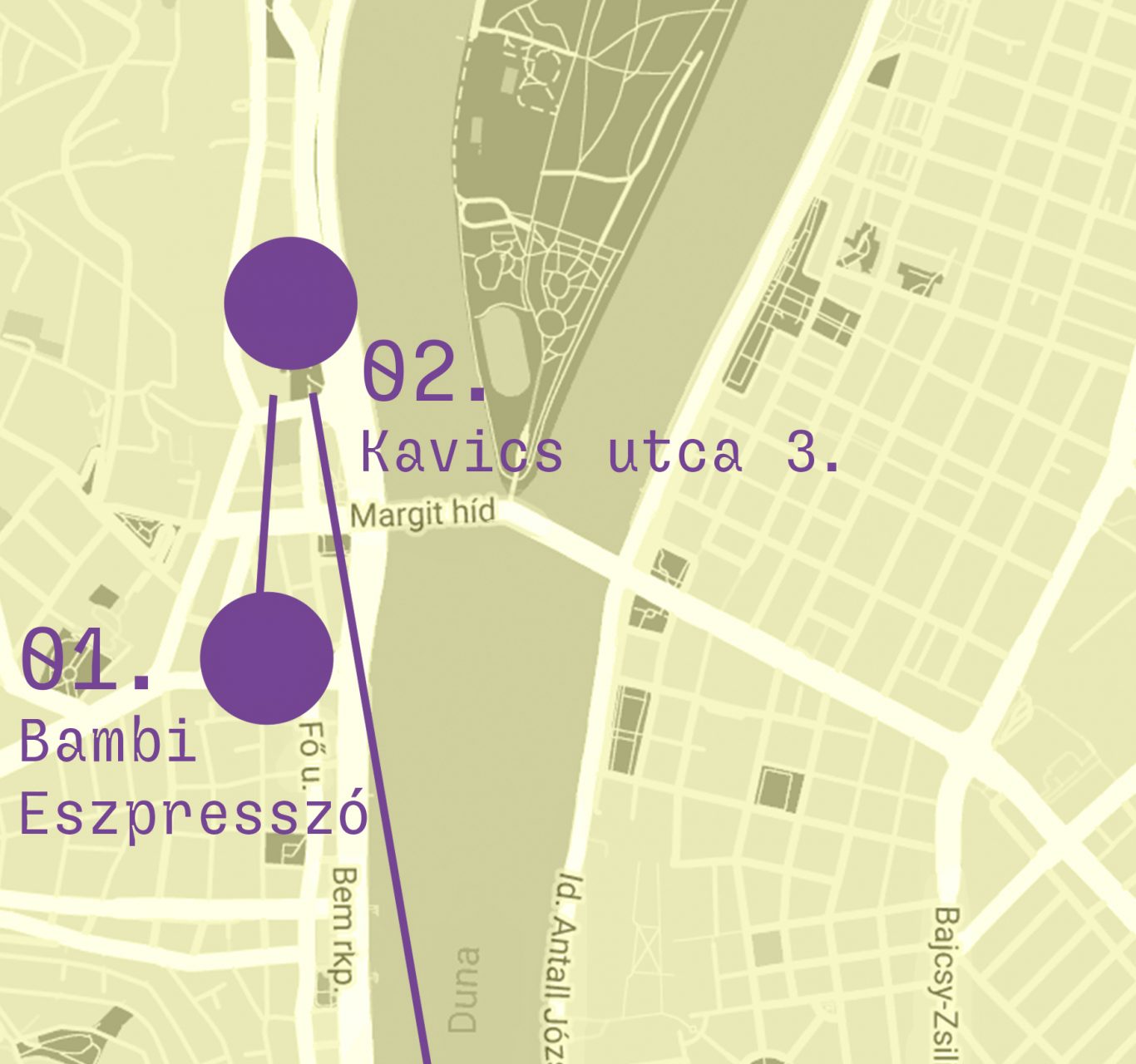

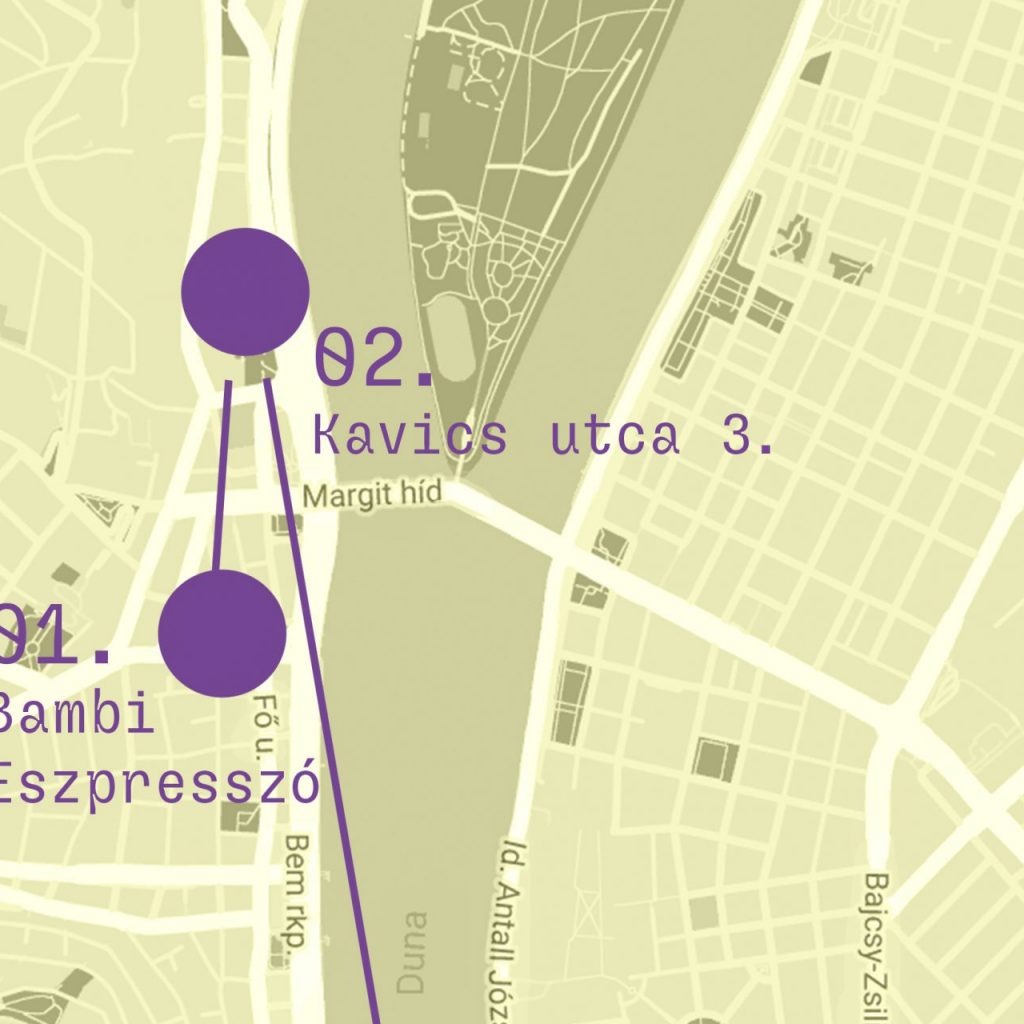

I was familiar with these artworks, so when making the selection I already knew the route they would trace. That said, I needed to walk it several times to make sure it complies with the rules of hiking challenges. I took less into account what this would mean to each target group. In the end, a route of more than 8 kilometres was created, which the hiking challengers completed in 2 hours, and the others by three and a half hours. But more important than the actual distance was to include major landmarks in the route. We start out from Bambi Café, walk along the Danube with the Parliament on one side, and the Buda Castle with a multitude of construction machinery on the other. Most of us is aware why this large-scale investment is happening and why it is problematic, which is why I wanted to include it in the walk. The same goes for the Statue of Liberty. Gellért Hill is undergoing major reconstruction, and the vicinity of the statue is inaccessible due to the barbed wires. My first reaction to being faced with this during my test tour was complete devastation, but I realised soon afterwards that it couldn’t be more perfect from the point of view of the project.

The subject of Polyphony that you also explored in depth in your thesis already came up. Though with a completely different background, Flaszter, the 1st Public Space Contemporary Art Biennale took place this year, exactly 30 years after Polyphony. In light of your own project, why do you think the subject of public space interventions is still so topical?

We simply still don’t feel ownership for public spaces. In terms of legitimacy, they are mostly appropriated by the power, which can also be economic– just think of the amount of advertisements surrounding us. This is the sort of appropriation that provokes us into action.

// /

Contributors to the Thinking by listening, listening by seeing project: Brigitta Ádi (concept/editing), Bettina Csarkó (sound), Bence Kovács-Vajda (sound post production), Angelika Kuthi (graphic design)