Eight and a Half Opportunities – Reinterpreting a Block in Józsefváros

Reuse and upcycling have become increasingly important concepts across all fields in recent decades. One of the most pressing issues of our time is overproduction and the resulting waste, which is slowly engulfing and making our planet uninhabitable. Recycling and circular use of materials are becoming crucial for more and more goods and services. Overproduction isn’t limited to everyday consumption; it also appears in architecture. In this context, first-year MOME MA students designed projects for the Nyolc és fél (Eight and a Half) art space in Józsefváros, focusing on reusing existing structures. Their diverse proposals aim to meet the needs of local residents by incorporating various new functions.

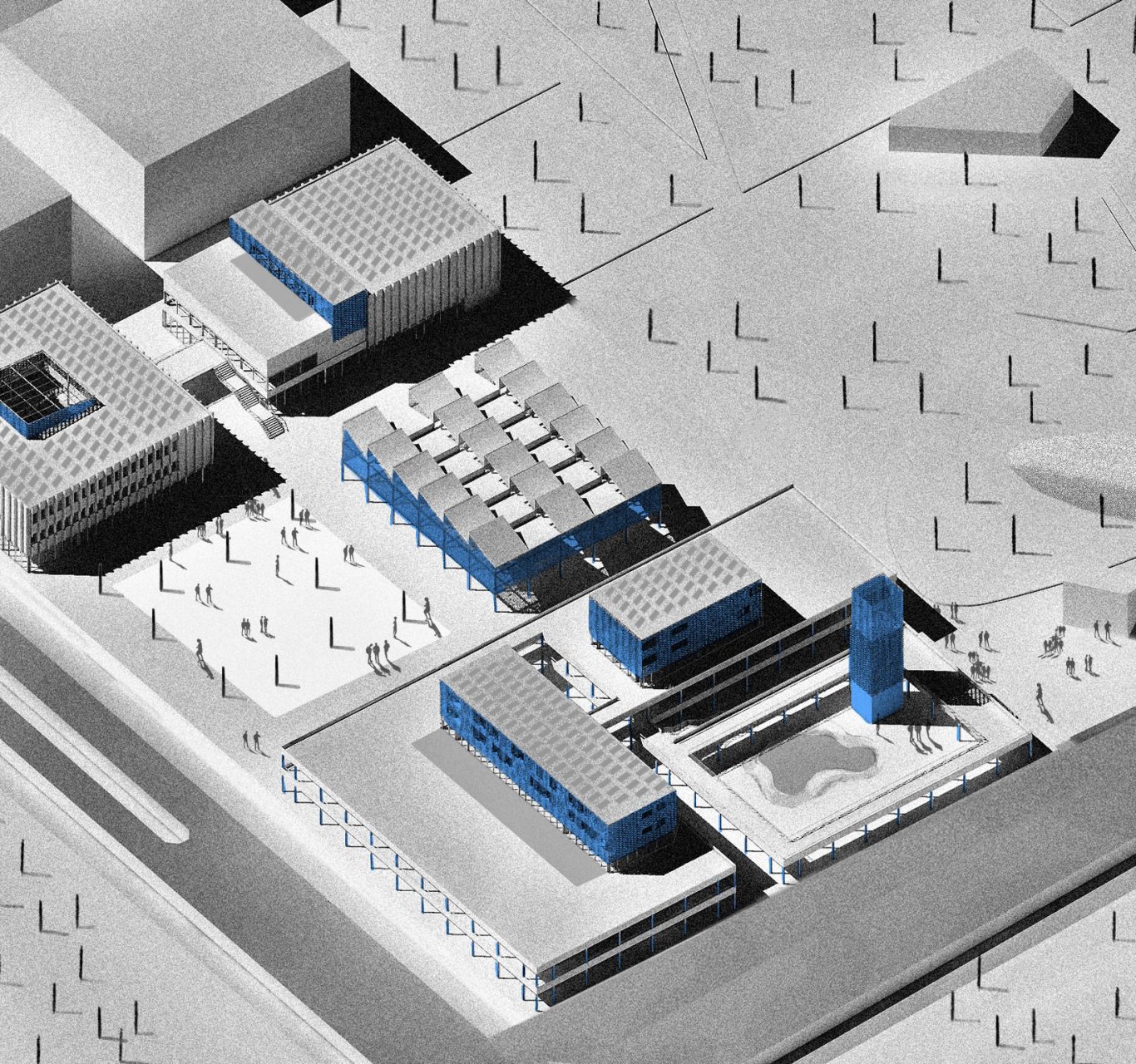

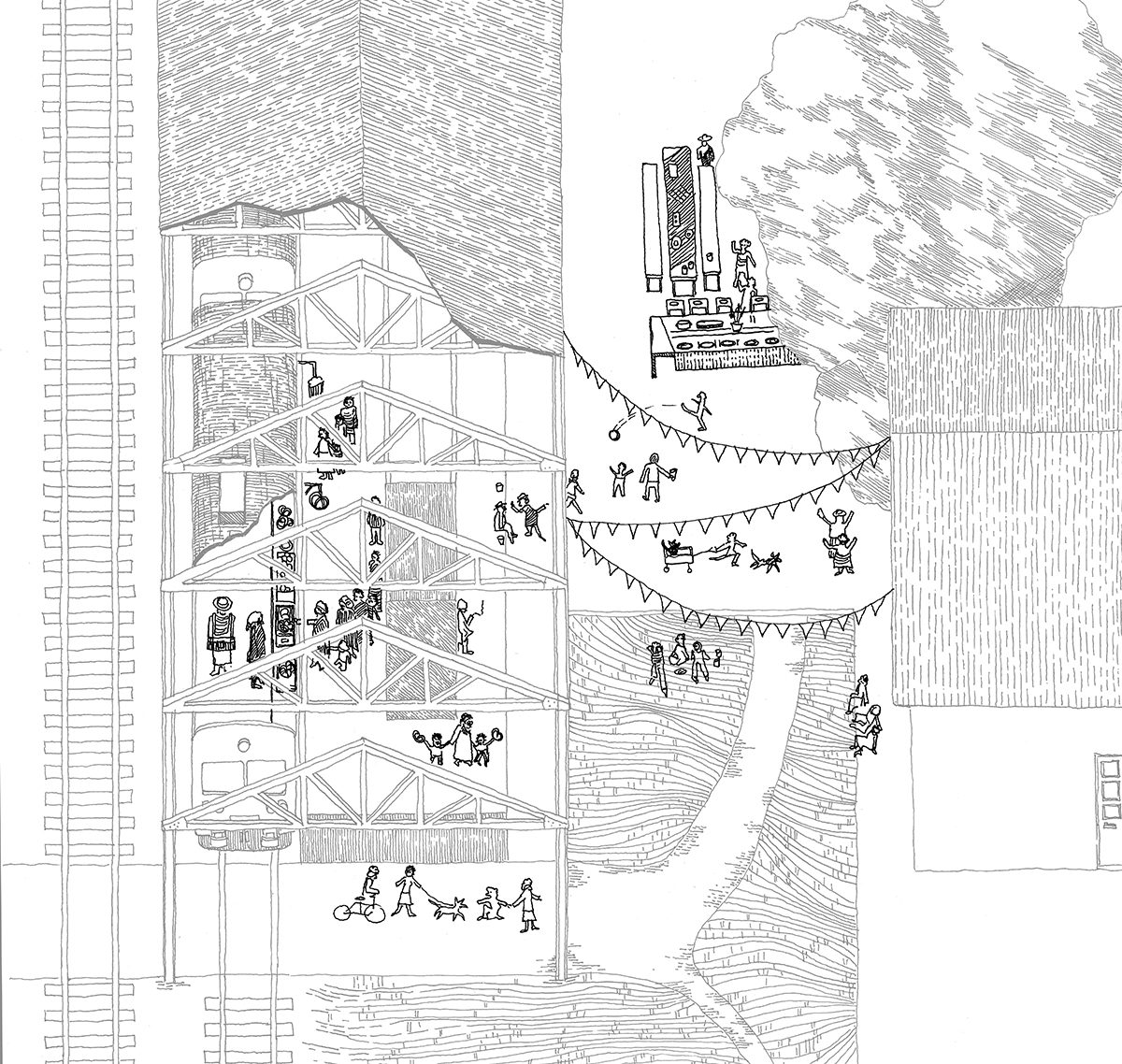

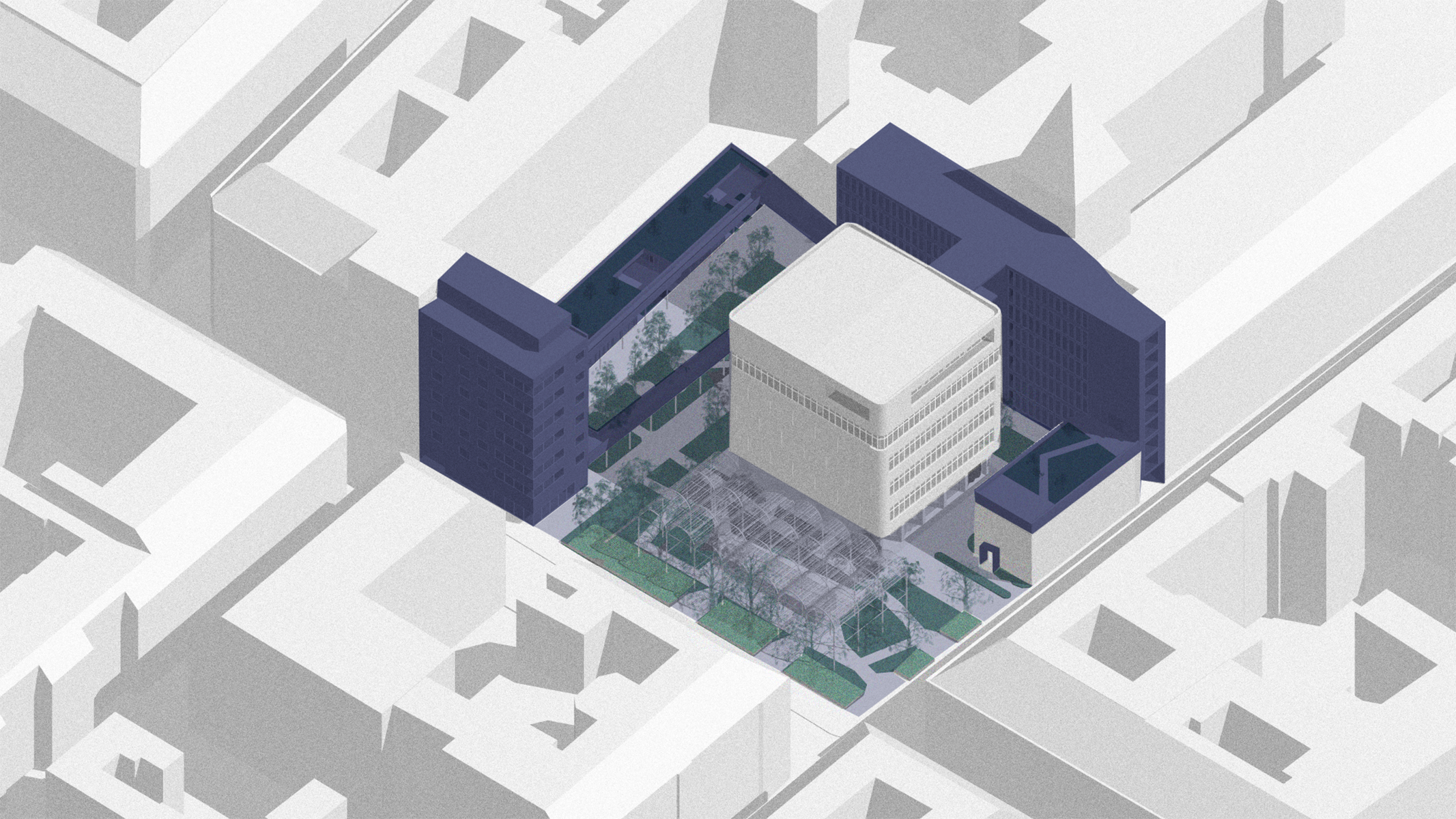

Design by Kata Csenge Szalay

Growing cities demand more housing and public buildings, often responded to by new investments and the construction of new districts, usually achieved by building on new areas. This urban sprawl and the resulting increase in density of the built environment, the constant expansion of cities and their encroachment on nature with new developments pose significant environmental and social problems. How to take an alternative path and offer solutions to overbuilding? One answer is upcycling – rethinking and reusing “lost and found objects”, in other words existing buildings that have lost their original function. This new approach, as opposed to designing new city quarters, offers creative and socially sensitive opportunities by reinterpreting the existing context. The task was undertaken by MOME Architecture MA students focusing on a block in Budapest’s 8th district.

The “lost and found object” in this case is a plot built to varying density in the Csarnoknegyed. Located at the corner of József and Német Streets, it houses the auxiliary buildings of the early 20th-century Telephone Exchange, designed by Rezső Ray and now converted into a luxury hotel. These structures were built in multiple phases: an air-raid shelter with a social realist façade was constructed in the 1950s, a narrow brick-covered connecting wing between the telephone exchange and the shelter in 1960s, and a brutalist concrete block (the “Distance Selector” building) in the 1970s to meet growing technological needs. A U-shaped, curtain-wall-clad structure served as a connection between the new block and the Telephone Exchange. This eclectic architectural mix reflects various styles and approaches, embodying the diversity of post-war political crises and technological changes as imprints of evolving needs and space use ideas of various eras. The traditional closed-block development is broken, with buildings set back from the street to create a paved area now used for parking. It also highlights another remaining structure, a two-story residential building extending far to the rear, now functioning as social housing for the district. Behind it, a new development maximises the buildable area with a high-rise apartment building. Interestingly, the investor owning this apartment complex also owns the plot but has left it untouched, allowing grassroots initiatives to flourish. After the closure of Dürer Kert, artist communities previously working there started occupying the complex, setting up studios, workshops, and hosting NGO-organised events, exhibitions, and gastronomy facilities. The area was named “Nyolc és fél” (Eight and a Half). Beyond recontextualising Federico Fellini’s influential film, it is a playful homage to the staggered levels between the cube and U-shaped buildings.

Design by Rebeka Posta

This currently underutilised collage of buildings, which features a montage of buildings with different characters, offers many spatial opportunities for upcycling. However, these potentials are not obvious and require detailed research and sociocultural mapping of the environment for drawing well-founded conclusions. The challenge is to create a programme and functions with broad social acceptance, community-building power, and spaces that meet local needs. Each semester project focused on space use supporting urban and community activities, featuring rentable studios, offices, exhibition spaces, cafeterias, and libraries. Housing functions also integrated, in the form of social housing, dormitories, or starter homes, promoting socially sustainable urban development, aiding various segments of society, and forging community. An important consideration was the interpretation and diverse use of spaces between buildings in an urban design context. Some envisioned a bustling city square to replace the parking lot, others created interesting spatial structures by reshaping the terrain or adding multifunctional pavilions in front of the buildings. The strip next to the complex was planned to reintroduce a natural environment with various parks, forests, and landscape elements. Finding the right balance between demolition, construction, and preservation to create a sustainable, well-functioning structure was a key challenge. Through site and contextual research, each student approached the design from different perspectives, resulting in various spatial solutions with interventions of different scales.

One common approach was to retain the existing building structure, discovering values and making minor interventions. Challenges included the half-level difference between the central block and the U-shaped building, the complex circulation system, and the elevated ground floor. Borbála Véghelyi’s project focused on the austere cube of the Distance Selector building. After thoroughly exploring and considering each level, she developed a thoughtfully constructed sequence of functions connected by a circulation system throughout the building, featuring exciting spatial situations, stands, and seating areas. She designed a social housing building to replace the old residential house, enclosing a more private garden, shielding it from the noise of the street. Utilising the setbacks, she created a landscaped public square in front of the building complex, emphasising open ground floors for quieter, more intimate spaces formed between the units.

Lili Gárdos retained most of the existing masses in her plan that explored walls and the role of walls in urban spaces. She enclosed the space in front of the building blocks with a wall, creating a more sheltered urban area. This wall integrates the various functions, with the various buildings sitting on top of it. The central cube was transformed into a community centre, surrounded by offices, studios, and new social housing building block integrated into the wall.

Janka Répás opted not to disrupt the organically developing spaces of “Eight and a Half”, leaving the buildings intact except for demolishing the bunker and planting an urban forest strip. Reflecting on the housing crisis, she designed a residential block in front of the complex, restoring the traditional closed-block development with an open ground floor for transparency and connectivity. Communal spaces on the ground floor and open walkways on the upper floors of the residential building help residents connect with each other and the environment.

Some students concluded that the excessive heterogeneity and intricate spatial structure of the complex required larger-scale interventions to create a cleaner, simpler system. Kristóf Lipótzy’s Stefan Lengyel award-winning design retained the three prominent masses (the central brutalist block, the bunker, and the curtain-wall building) with minor modifications, making the space between buildings walkable. With this intervention and the creation of a multi-level public forum adjusted to the elevated ground floor, he dissolved the enclave-like nature of the current artist colony, opening up and making the area accessible to everyone. The central block houses communal functions, workshops, offices, and a dining area on the ground floor, while the bunker contains a music performance space, with a dormitory attached. On the other side, a quieter park is framed by a social housing complex, symbolically separated from the bustling forum by a covered-open corridor.

Lili Vokó proposed reprogramming the space in front of the building complex, freeing the strip along Német Street by demolishing the bunker and creating a landscaped public square. She added a flexible community space parallel to the landscaped area and designed a row of duplex houses with a shared internal garden in the back. Streets running between the building strips allowed for exploring the entire area. A hidden yet accessible playground was situated in the farthest corner.

These and other interventions with a similar scale were made, involving varying degrees of demolitions and additions. While it is difficult to provide a one-size-fits-all solution to such a such a complex spatial challenge, the student projects presented diverse designs fitting the urban context, revealing and complementing the current values of the building block.

The examples listed clearly illustrate that the role of contemporary architecture has long since moved beyond the narrow confines of purely technical and professional architectural design. It is a much more complex and comprehensive task, often starting with uncovering existing values and areas that could be creatively transformed into new living spaces within cities. Essential aspects to consider in the design and implementation process include social needs, environmental impacts, sustainability, and flexibility. A sensitive, less profit-oriented approach is necessary to address complex issues and create truly liveable environments: spaces that are not wasteful but inclusive, thoughtful, and accessible to all users.

Design by Oskar Koppány Szelevényi

// /

The works were completed at the Architecture MA programme of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, under the guidance of Zsófia Csomay and Balázs Marián, and help from Melinda Benkő.

Students of the course: Azevedo Rita, Enikő Balogh, Dorottya Filoména Füleky, Lili Gárdos, Kristóf Lipótzy, Zsombor Nyuli, Ádám Oltvai, Kien Pham, Rebeka Posta, Janka Répás, Sousa Vasco, Kata Csenge Szalay, Oskar Koppány Szelevényi, Imre Szűcs, Bori Tóth, Borbála Véghelyi, and Lili Vokó.