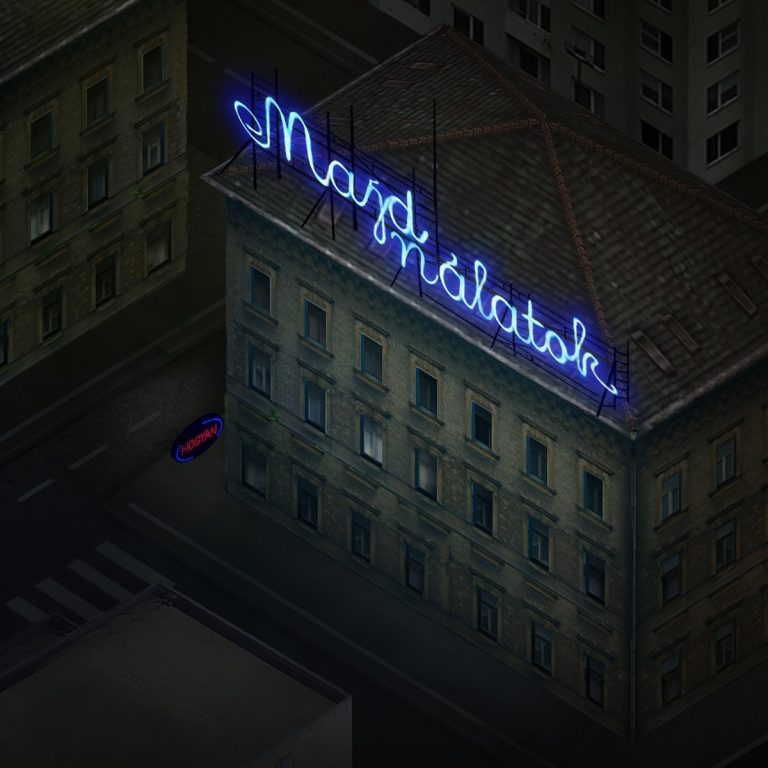

“It’s a completely DIY studio” – Interview with the developers of the game Majd nálatok

In March this year, Studio CiGi released its very first point-and-click game, Majd nálatok, where players can immerse themselves in the surreal, quirky world of downtown Budapest through the eyes of a young adult. The game development team consists of just two people: designer Zsanna Kili and programmer János Hegymegi. Zsanna was responsible for the story, graphics, and text elements, though many of the significant content and structural decisions were made together. Venturing into the uncharted territory of game design, they embarked on a complex creative process with identities blurred and design roles and practices imperceptibly bleeding into each other.

How was the design process structured? What challenges did you need to overcome during the development of the game?

Zsanna: It would have been much easier for János if I could have outlined the entire framework from the beginning, but it happened the other way around. It was put together rather naively. We had some of the details, like the setting in an imaginary Budapest with distinctive characters, situations, and locations that needed to be connected somehow. My goal was to capture essential impressions and atmospheres – I had a clear vision of the visual world I wanted, and I gave it a lot of thought. I started drawing the first location while I was on Erasmus. Being abroad helped a little.

To be able to see it from the outside?

Zsanna: Yes, I felt both overwhelmed and depressed by and somewhat romantic about it. The young adult-university student period felt tangible. I was concerned it would turn into navel-gazing though. There are some universal experiences that resonate with twenty-somethings in Hungary.

Did the fact that it evolved a lot benefit the final product?

Zsanna: It helped in some ways, but I assume it made things more complicated for János. For a while, it was even a question whether what we were making could be called a game, but it gradually grew into one. We also thought a lot about how much guidance the player should be given and whether there should be conventional quests. The game design clearly had a lot of potential.

János: We might have skipped some standard game design practices. I can trace it back to not including many mechanics that require extensive planning. I’m not sure if it’s a problem to make a minestrone soup by tasting and seasoning as you go, or if you should use the French mise en place method, prepping everything in advance. I generally prefer the latter, but in this case, we only did as much designing as was necessary at any given time.

Do you think this mutual blurring the lines and intangible crossovers between genres have benefited the game?

Zsanna: I absolutely do, I don’t think it needs to be strictly one way or the other. Alongside my diploma project, my thesis explored the differences between low and high art. Some genres, tastes, and subcultures have wider social recognition, attracting more power, money, and capital. This led me to the realisation that the game I was designing fell into the cathegory of low art. I was curious to see what it will turn out like and who it would resonate with.

János: These considerations were not at all obvious on a theoretical level during the making of the game. I think she made these decisions and translated them into practical design questions. I usually agreed with her ideas. Specific situations required certain game mechanics for changes to happen within the game. I wasn’t concerned with questions of low or high art, but rather how to turn it into a game. From my perspective, anything you can interact with and influence is a game. Of course, clever ‘packaging’ also matters.

Zsanna: To be fair, we didn’t overthink the packaging.

János: I mean presenting it as a game. We have a website where anyone can see in a second that this is a game development team from Budapest, and here’s their first game. No fuss, no registration, just play.

It’s indeed user-friendly. Was that a conscious decision or just for simplicity’s sake?

Zsanna: It was an important consideration. Lowering the entry barrier, you click and it starts relatively fast. I think browser games are fantastic.

János: The entertainment industry’s capitalist logic has taken video games in an increasingly worse direction over the last few decades. I believe – not just because of nostalgia but also on principle – that a browser game should be public and accessible to everyone. This was never called into question.

Zsanna: In big game studios, artistic freedom is often restricted by financial considerations. Obviously we could do what we wanted, but it wasn’t sustainable – we both had other jobs, which is why it took so long. In some ways, having this lengthy process was good because it allowed us to include things that might have been omitted otherwise. But it was tough…

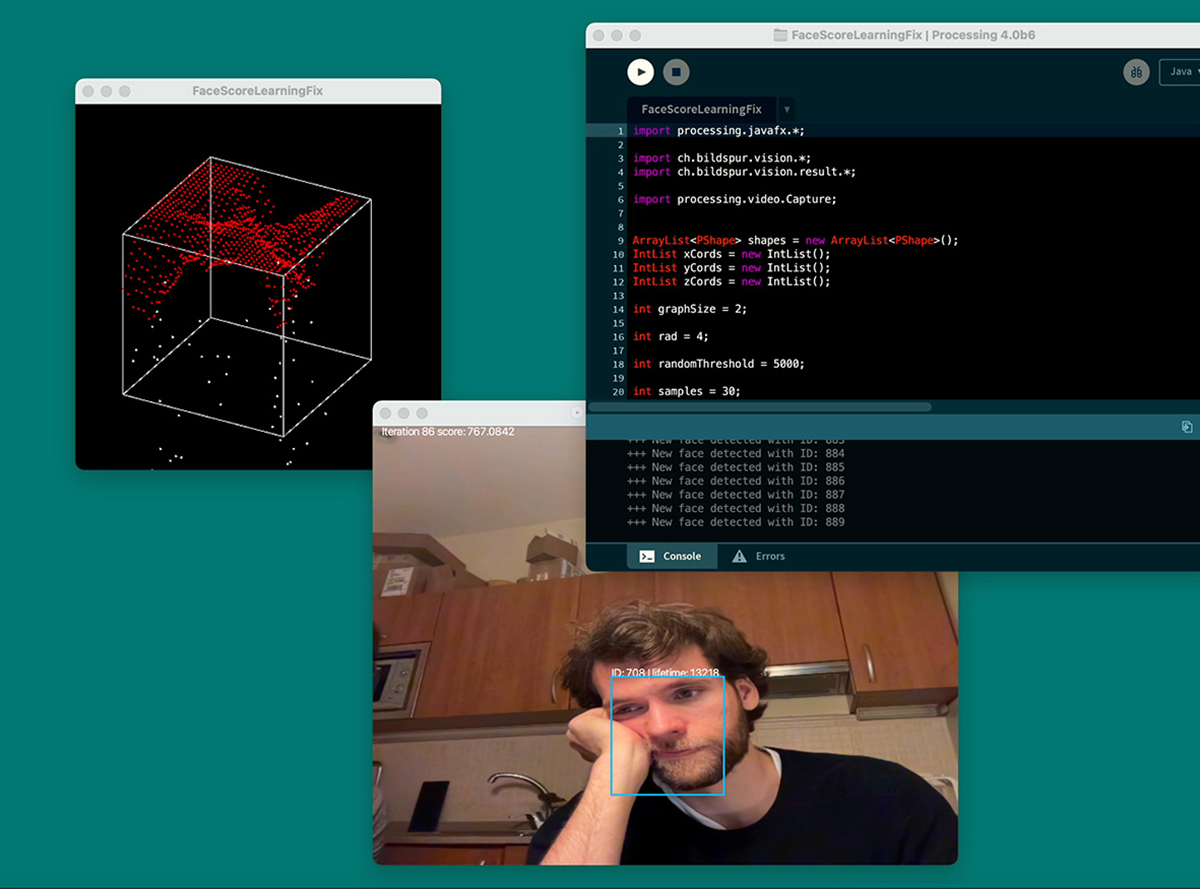

János: To mentally and technically keep up. Overall, when making this type of game, it’s the content and not necessarily the structure that determines how timeless it will be. Our game is relatively low to medium complexity. It was practical for us to test what is it we could do ourselves. This is a completely DIY studio. The framework we used to code was open source, chosen from the get go to avoid legal or financial issues.

I felt Majd nálatok reflects on how social determinants of people’s well-being are heavily marginalised, with systemic issues being naturally individualised and psychologised.

Zsanna: That’s all in there. I tried to incorporate all this – ultimately this is what the game’s supposed to be about. Some topics could have been more direct. The image of a university student from downtown Pest living in a chaotic, decadent environment is usually more powerful. But that’s not the point. It’s just the frills.

János: The ending of the game also reflects and sends a message on these issues. For example, how you can be in a social setting, go through the same experiences, yet not feel fulfilled. Experiences like these influenced my decisions throughout the game development.

It’s hard not to draw parallels between the game’s bleak “diagnosis” and its lengthy development process.

Zsanna: Indeed, the design process felt much like the game itself.

How do you feel about the final outcome?

Zsanna: Ultimately, it was PC Guru that wrote about it, not Artmagazin (laughs). Those who enjoy playing games probably found something in it.

János: It’s great that designing a game is so accessible for anyone today. The hardest part is committing to a game idea, but learning from my own mistake, I recommend anyone interested in development to start with recreating an existing game, like Tetris, instead of waiting for a lucky break (laughs). They’ll experience much of what we’re talking about here. I’m grateful for all that I’ve learned, and it’s amazing how many people it has reached.

// /

The project was completed at the Media Design MA programme of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design