Recapturing the “fallen front” – Rebeka Winkler’s architectural design

“You’ve stolen our culture!”; “Give back our cultural space!”; “This was a cultural hub for the Roma, I grew up here!” These are just some of the impassioned messages scrawled on the locked gates of 6 Tavaszmező Street. On 24 October 2016, without prior consultation, the Roma Parliament – a vital centre of Roma civil activism for 25 years – was forcibly evicted from the building. “This front has fallen too…”, wrote Tímea Junghaus in an obituary for the Józsefváros-based institution. Although the government had announced plans for the Cziffra György Roma Cultural and Educational Centre at the site, eight years have passed with no sign of the proposed institution, while the former home of the Roma Parliament remains abandoned and untouched as a stark symbol of Roma cultural appropriation. The building has now been reimagined by architect Rebeka Winkler.

From a 2024 perspective, the post-regime change years saw a flourishing Roma civil rights movement. As Rebeka highlights in her research, during this period the Roma were recognised as a nationality, and despite the limited political power of the newly formed minority governments, Roma self-organisation gained momentum within the revitalised public sphere. The establishment of the Roma Parliament marked a key milestone in the movement, serving as an umbrella organisation for over 100 smaller Roma initiatives. As the first non-governmental Roma organisation, it aimed to carve out a space for itself where minority governments had previously struggled: in politics.

The building on Tavaszmező Street was once a vibrant hub of civil and cultural life, housing the Phralipe Association, which supported the first Roma self-organisation, as well as the Roma newspaper Amaro Drom. It also featured the only permanent Roma fine art exhibition, showcasing around 250 works. This vital space for preserving and promoting Roma culture extended beyond the Roma community, offering a platform for intercultural exchanges. Over nearly three decades, this centre of value creation gradually fell victim to government policies aimed at dividing Roma organisations. Among the critics of the government’s heavy-handed intervention was artist Norbert Oláh, who, in a performance, symbolically broke through a wall of anxieties and fears “built” in front of the closed building. While the Roma Parliament still exists, the seizure of its physical home has dealt a significant blow to the urban Roma community’s struggle against marginalisation.

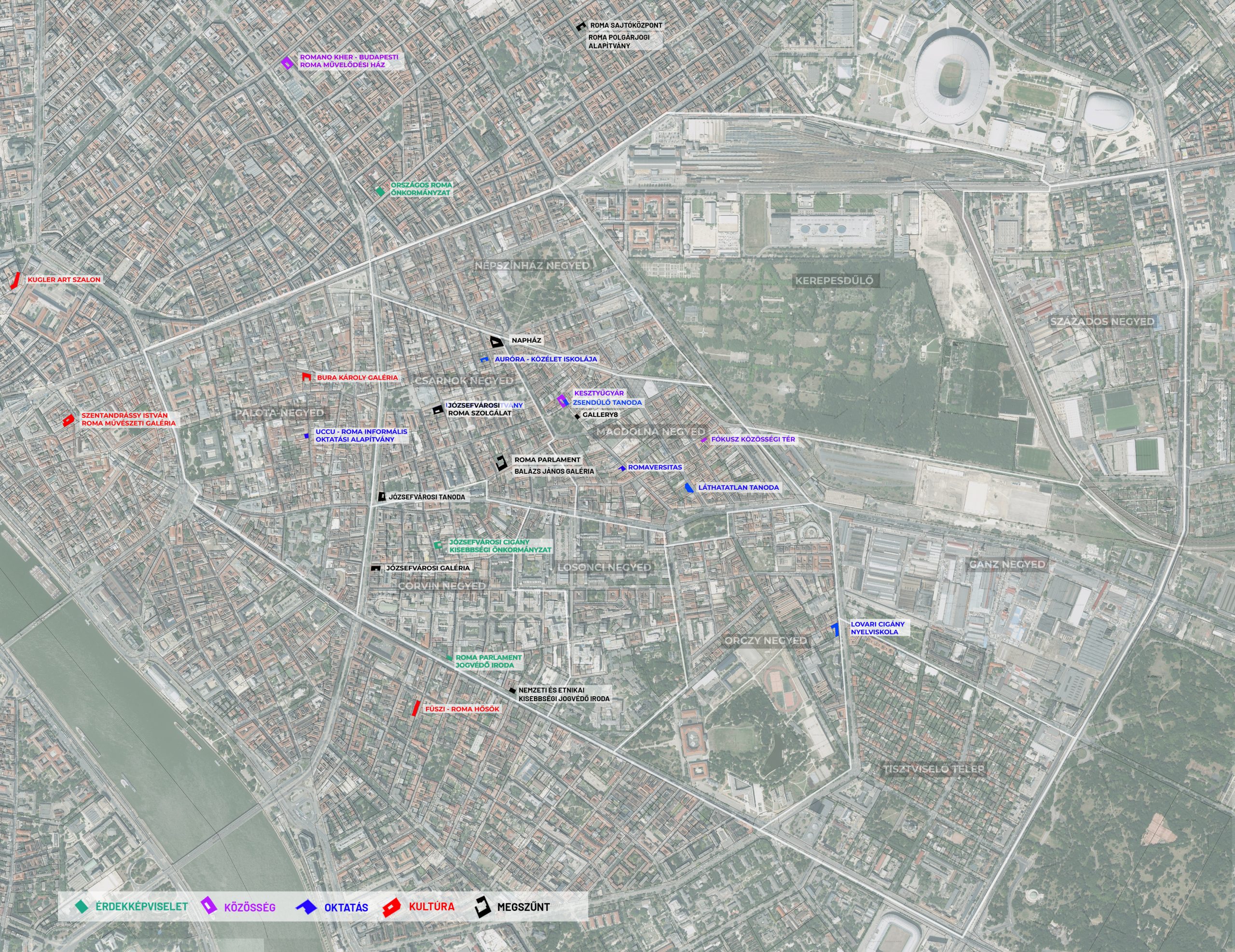

Rebeka’s map is showcasing the closed and still operating roma institutions

A glance at Józsefváros today shows that all is not lost: various Roma advocacy, educational, cultural, and community organisations continue to operate independently. What’s more, in recent years, professional discourse has also created a “conceptual space”: since the 2000s, the RomaMoma project, which envisions a Roma contemporary art museum, has returned to the agenda at the most recent OFF-Biennale. The Roma civil rights movement hasn’t disappeared – it has evolved. While the civil sector is being starved off, hampered by a lack of funding and fragmented by the silencing of professional groups, the movement’s sense of duty endures. Rebeka’s redesign of the Roma Parliament building is deeply rooted in this conscious presence. As she notes:

“[…] it’s not about envisioning institutions for the Roma that never existed, but about sustaining or reviving those that have already been established and proven successful.”

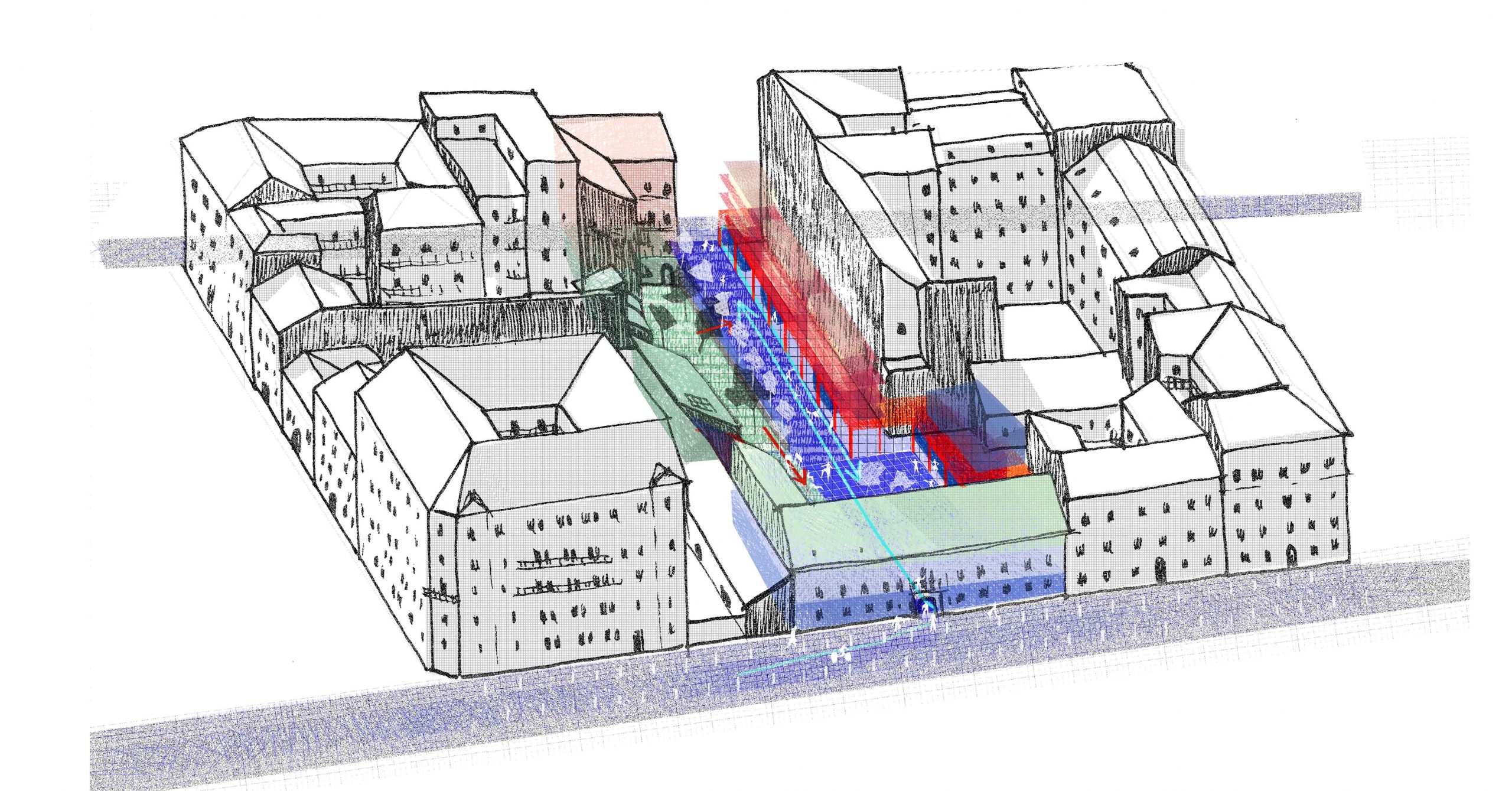

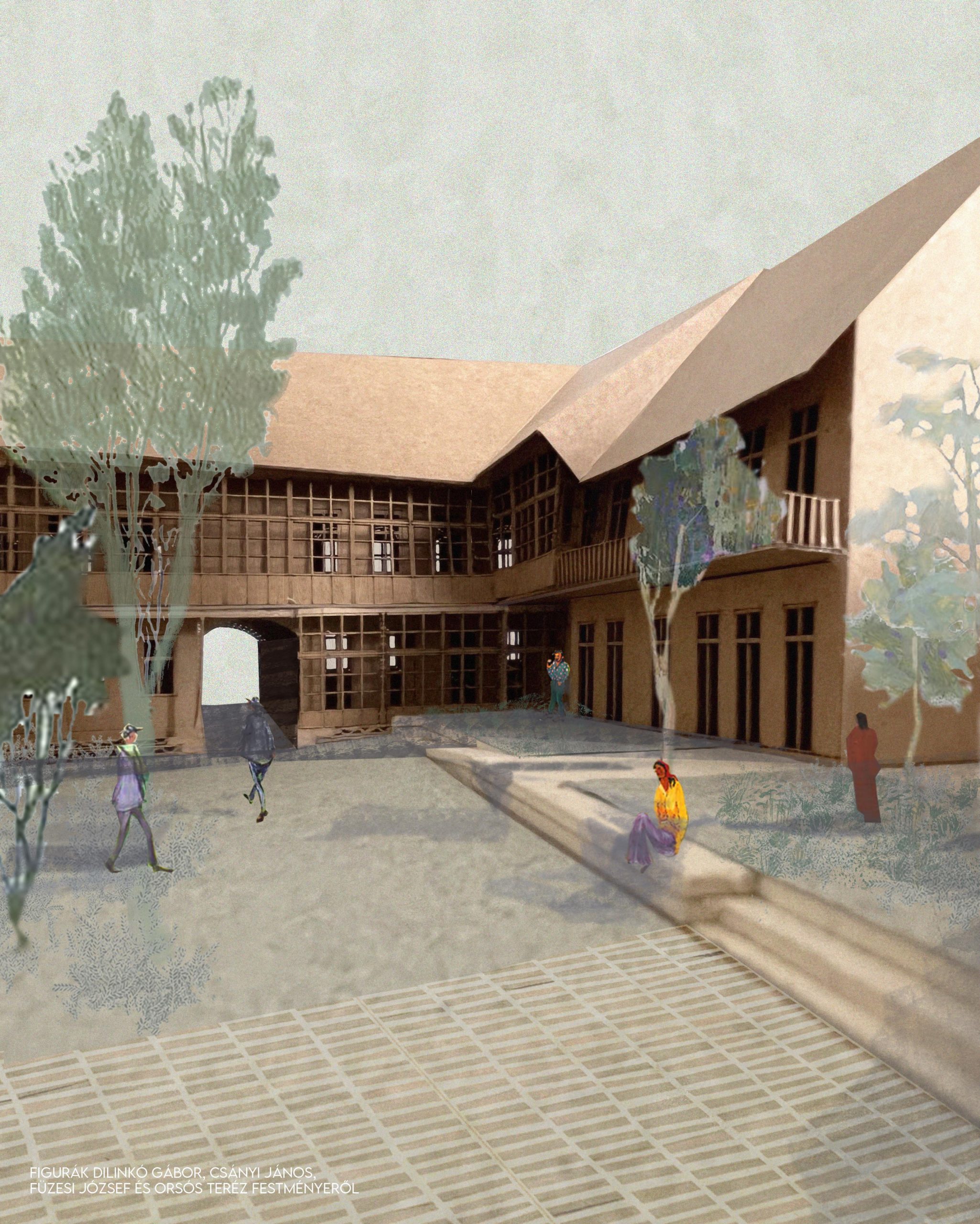

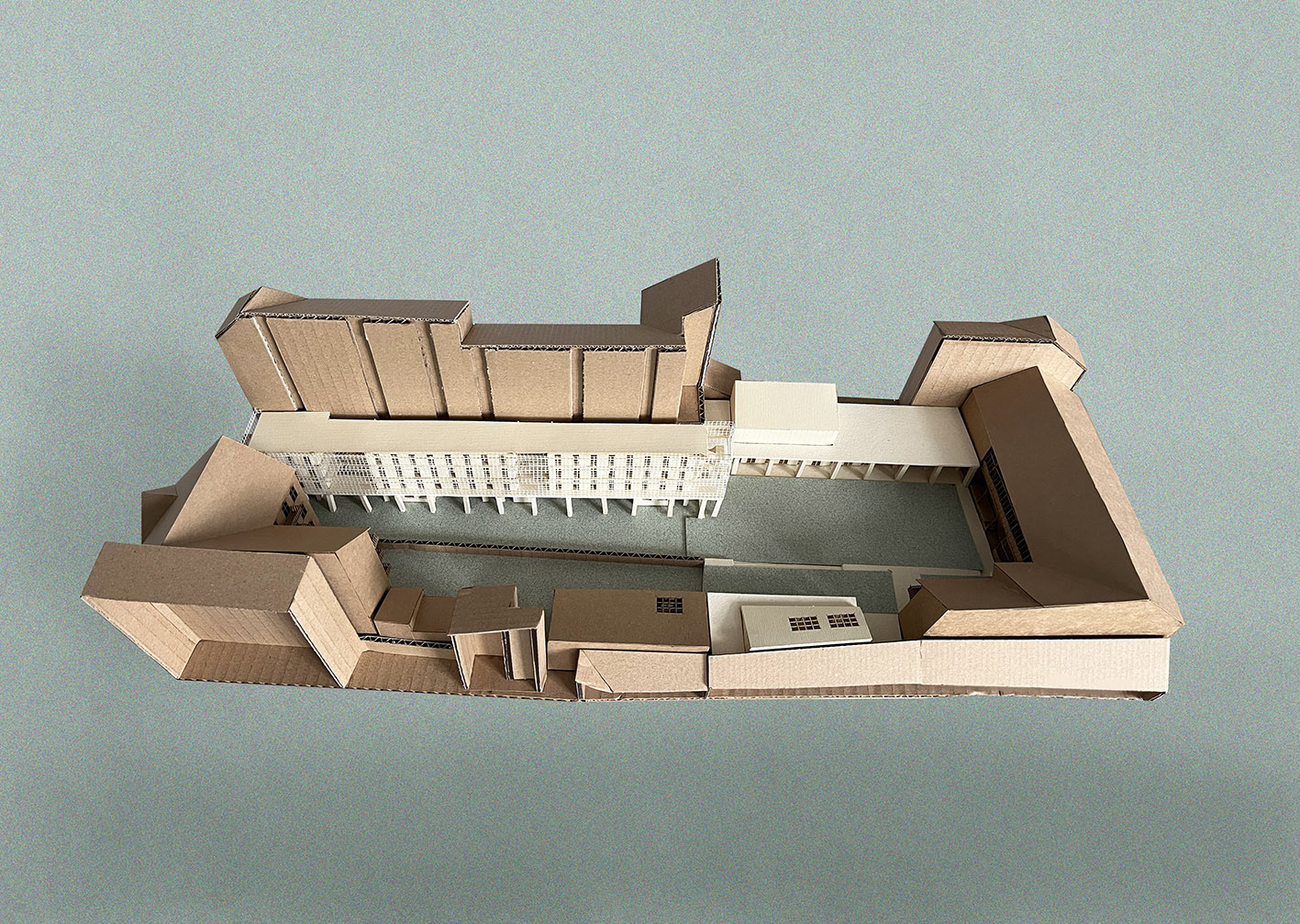

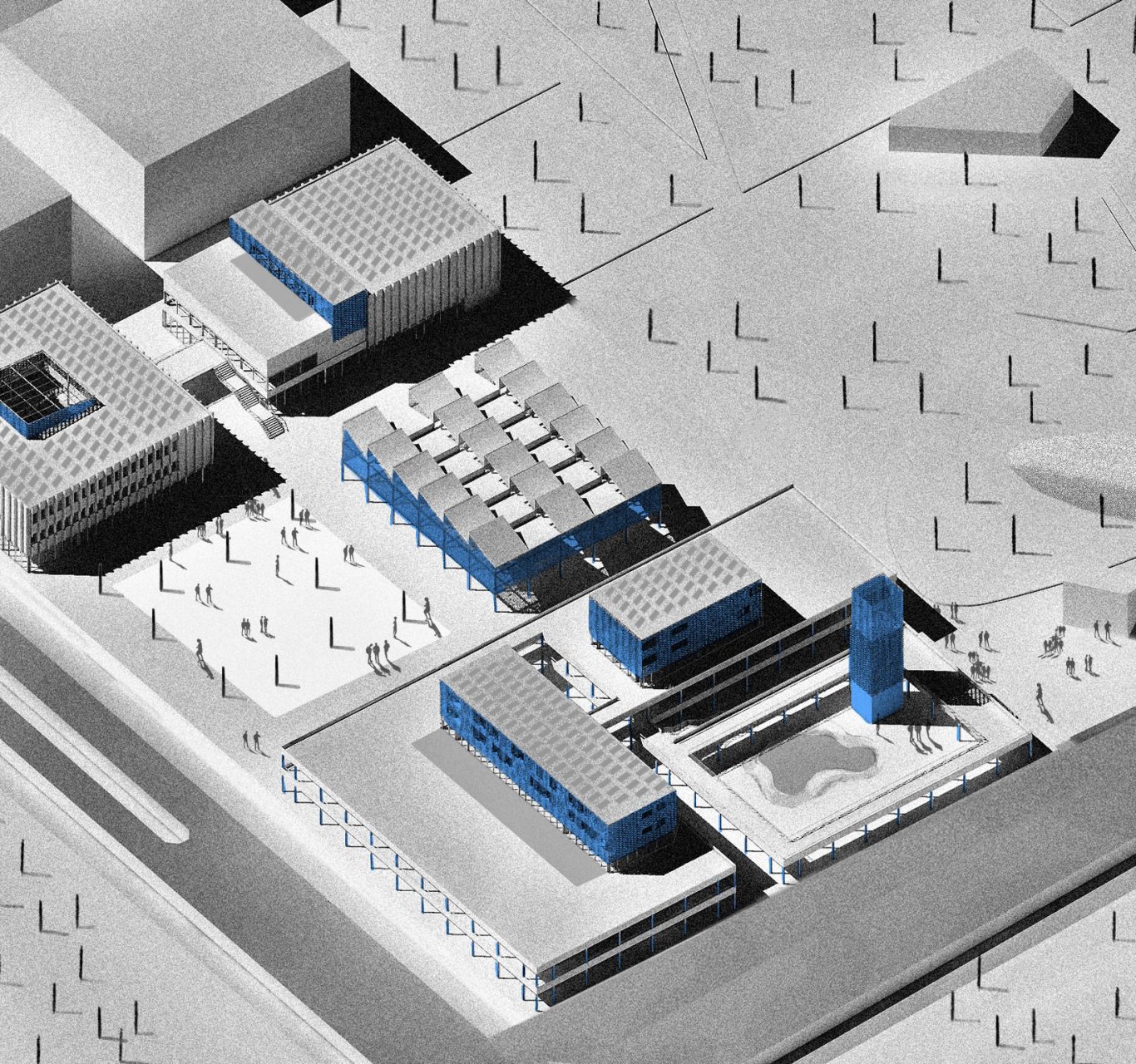

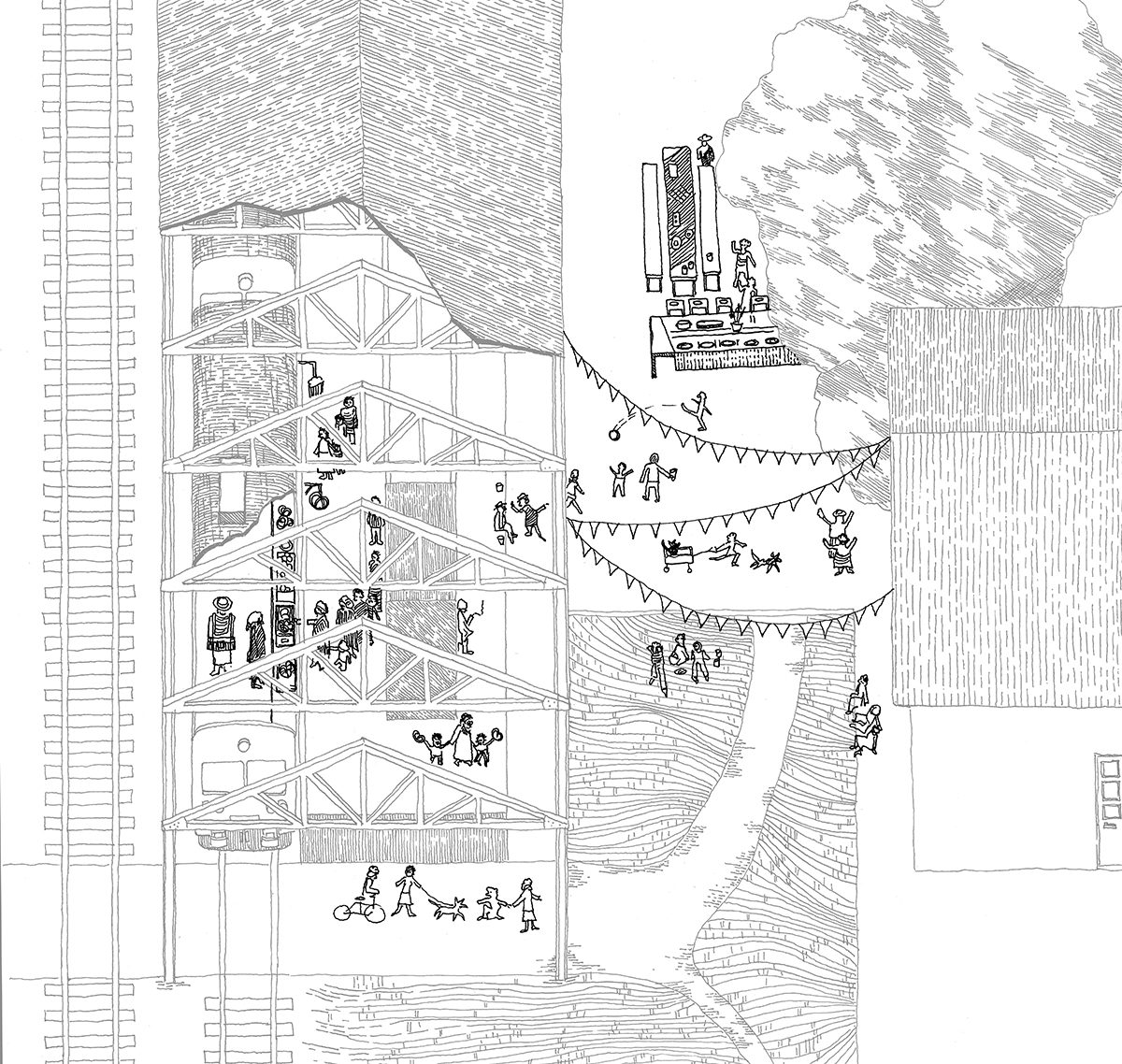

The building, located on a site that stretches from Tavaszmező Street to the parallel József Street, was designed in the 19th century as a stone carving and sculpting workshop. The L-shaped structure hugs the central courtyard, featuring a striking glass arcade that overlooks the inner space and a stairwell adorned with frescoes. Today, the former workshop is divided into three parts: the old Roma Parliament building, the Martsa Studio, and a vacant lot used as a car park. Rebeka’s spatial design transforms the previously enclosed courtyard into a passage-like public space bordered by both open and covered areas, making the entire site accessible. It preserves the original community and cultural functions of the building – the offices of the NGOs, creative spaces, and exhibition areas – while introducing new features, such as a residence hall to address housing challenges.

It is no easy feat for an architect to work with a building steeped in both cherished and painful memories. Yet, in Rebeka’s approach, the invisible is brought back into view, and her fresh vision allows it to be reimagined. The practical realisation begins where we let our imagination reclaim what has been lost.

// /

Rebeka Winkler’s diploma project Roma Parliament and Community Centre – Urban Space on Tavaszmező Street was completed as part of the Architecture MA programme at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, with Balázs Marián as her supervisor and Beáta Molnár as her consultant.